Deep in the Andean rainforest, the bark from an endangered tree once cured malaria and powered the British Empire. Now, its derivatives are at the centre of a worldwide debate.

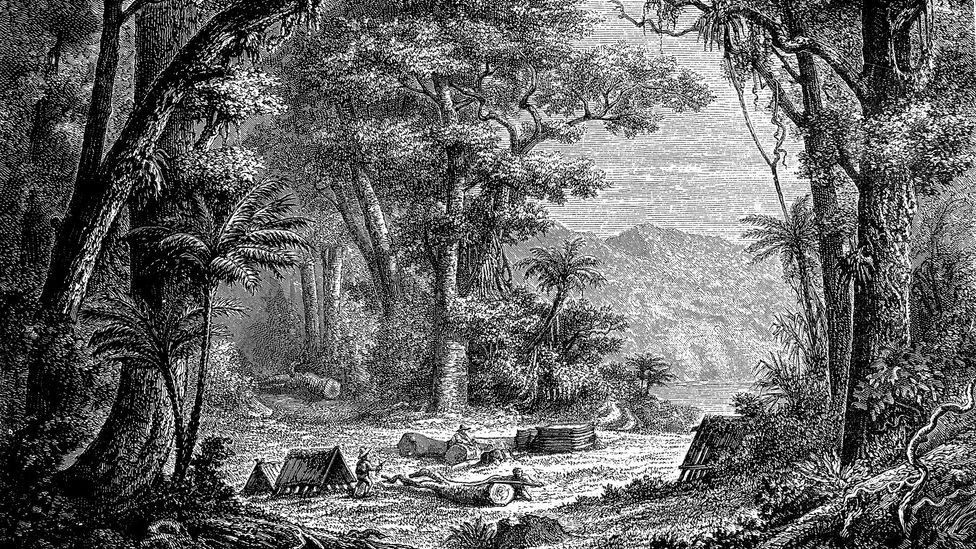

Unfurling in a carpet of green where the Andes and Amazon basin meet in south-western Peru, Manú National Park is one of the most biodiverse corners of the planet: a lush, 1.5-million hectare Unesco-inscribed nature reserve wrapped in mist, covered in a chaos of vines and largely untouched by humans.

Where to see the rare cinchona tree

Manú National Park, Peru: A haven of biodiversity, the Unesco nature preserve is home to an estimated 5,000 plant species.

Podocarpus National Park, Ecuador: One of the last places to spot Ecuador’s national tree. Hiking through its misty trails, you may also encounter the spectacled bear, one of the Andes’ most emblematic animals.

Cutervo National Park, Peru: Peru’s oldest protected area is famous for its pre-Columbian archaeological remains, 88 species of orchids and for being the last remaining cloud forest in the Peruvian highlands.

Semilla Bendita Botanical Garden, Peru: This botanical garden operated by local environmentalists is home to more than 1,300 native species – including orchids and cinchonas.

But if you hack your way through the rainforest’s dense jungle, cross its rushing rivers and avoid the jaguars and pumas, you may see one of the few remaining specimens of the endangered cinchona officinalis tree. To the untrained eye, the thin, 15m-tall tree may blend into the thicketed maze. But the flowering plant, which is native to the Andean foothills, has inspired many myths and shaped human history for centuries.

“This may not be a well-known tree,” said Nataly Canales, who grew up in the Peruvian Amazonian region of Madre de Dios. “Yet, a compound extracted from this plant has saved millions of lives in human history.”

Today, Canales is a biologist at the National Museum of Denmark who is tracing the genetic history of cinchona. As she explained, it was the bark of this rare tree that gave the world quinine, the world’s first anti-malarial drug. And while the discovery of quinine was welcomed by the world with both excitement and suspicion hundreds of years ago, in recent weeks, this tree’s medical derivatives have been at the centre of another heated global debate. Synthetic versions of quinine – such as chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine – have been touted and largely disputed as possible treatments for the novel coronavirus.

For centuries, malaria, a disease caused by a mosquito-borne parasite, has plagued people across the world. It ravaged the Roman Empire; it killed between 150 to 300 million people in the 20th Century; and, according to the World Health Organization, nearly half of the world’s population still lives in areas where the disease is transmitted.

Medieval remedies to cure “mal aria” (“bad air” in Italian) reflected the erroneous belief that it was an airborne disease and ranged from bloodletting to limb amputations to cutting a hole in the skull. But in the 17th Century, the first known cure for it was allegedly found here, deep in the Andes.

According to legend, quinine was discovered as a malaria cure in 1631 when the Countess of Cinchona, a Spanish noblewoman married to the viceroy of Peru, fell ill with a high fever and severe chills – the classic symptoms of malaria. Desperate to heal her, the viceroy gave his wife a concoction prepared by Jesuit priests made with the bark of an Andean tree and mixed with clove and rose-leaf syrups and other dried plants. The countess soon recovered and the miraculous plant that cured her was named “cinchona” in her honour. Today, it’s the national tree of Peru and Ecuador.

People across Europe began writing about a ‘miraculous’ malaria remedy discovered in the jungles of the New World

Most historians now dispute this tale, but as with many legends, parts of it are true. Quinine, an alkaloid compound found in cinchona’s bark, can indeed kill the parasite that causes malaria. But it wasn’t discovered by Spanish Jesuits.

“Quinine was already known to the Quechua, the Cañari and the Chimú indigenous peoples that inhabited modern-day Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador before the arrival of the Spanish,” said Canales. “They were the ones that introduced the bark to Spanish Jesuits.” The Jesuits crushed the cinnamon-coloured bark into a thick, bitter powder that could be easily digested. The concoction came to be known as “Jesuits Powder”, and soon, people across Europe began writing about a “miraculous” malaria remedy discovered in the jungles of the New World. By the 1640s, Jesuits had established trade routes to transport cinchona bark throughout Europe.

In France, quinine was used to cure intermittent fevers of France’s King Louis XIV at the court of Versailles. In Rome, the powder was tested by the Pope’s private physician and distributed for free by the Jesuit priests to the public. But in Protestant England, the drug was met with some scepticism, as some doctors labelled the Catholic-promoted concoction a “papal poison”. Oliver Cromwell allegedly died of malarial complications after refusing “Jesuit Powder”. Nevertheless, by 1677, cinchona bark was first listed by the Royal College of Physicians in its London Pharmacopoeia as an official medicine used by English physicians to treat patients.

To fuel their cinchona craze, Europeans hired locals to find the precious “fever tree” in the rainforest, scrape its bark with a machete and take it to cargo ships awaiting in Peruvian ports. Increased demand for cinchona quickly led the Spanish to declare the Andes “the pharmacy of the world”, and as Canales explained, the cinchona tree soon become scarce.

Cinchona’s value soared during the 19th Century, when malaria was one of the greatest threats faced by European troops deployed in overseas colonies. According to Dr Rohan Deb Roy, author of Malarial Subjects, obtaining adequate supplies of quinine became a strategic advantage in the race for global domination, and cinchona bark turned into one of the world’s hottest commodities.

Quinine is frequently cited by historians as one of the major ‘tools of imperialism’ that powered the British Empire

“European soldiers engaged in colonial wars frequently died of malaria,” said Deb Roy. “Drugs like quinine enabled soldiers to survive in tropical colonies and win wars.”

As he explains, cinchona was especially used by the Dutch in Indonesia; by the French in Algeria; and most famously, by the British in India, Jamaica and across South-East Asia and West Africa. In fact, between 1848 and 1861, the British government spent the equivalent of £6.4m each year importing cinchona bark to store for its colonial troops. As a result, quinine is frequently cited by historians as one of the major “tools of imperialism” that powered the British Empire.

“Much like countries today are rushing to get to a Covid-19 vaccine to get a competitive advantage, countries back then rushed to get quinine” explained Patricia Schlagenhauf, a professor of travel medicine at the University of Zurich specialising in malaria.

Churchill allegedly said the drink had saved ‘more Englishmen’s lives, and minds, than all the doctors in the Empire’

It wasn’t just cinchona bark that was valuable. Its seeds become a high-demand commodity too. “British and Dutch governments wanted to plant cinchona in their own colonies to stop their dependence on South America,” Deb Roy explained. But choosing the right seed wasn’t easy. Each of the 23 species of cinchona has a different quinine content. It was thanks to locals with indigenous botanical knowledge that Europeans could secure quinine-rich species to export abroad.

By the mid-1850s, the British had successfully established “fever tree” plantations in southern India, where malaria was rampant. Soon, British authorities started distributing locally harvested quinine to soldiers and civil servants. It’s long been rumoured that they allegedly mixed gin with their quinine to make it more palatable, thus inventing the first tonic water and the famous gin and tonic drink. Today, small amounts of quinine are still found in tonic water. But as Kim Walker, who co-authored the book Just the Tonic points out, this British origin story is likely a myth. “It seems like they added whatever was handy” – be it rum, brandy or arrack, she explained.

Plus, as Schlagenhauf adds, quinine has a short lifespan in the body so sipping on a gin and tonic at cocktail hour would not be enough to guarantee protection against malaria. Nevertheless, the myth of gin and tonic as a potent anti-malaria prevention tricked even Winston Churchill, who allegedly said the drink had saved “more Englishmen’s lives, and minds, than all the doctors in the Empire.”

Of course, the gin and tonic is just one drink tied to the “fever tree”. Today, the most famous cocktail in Peru may be the American-invented pisco sour, but the most popular among Peruvians is arguably the bitter, quinine-flavoured pisco tonic, a homegrown invention that’s often mixed with maiz morado (purple corn) from the Andes to make a pisco morada tonic. If you’ve ever sipped liqueurs like Campari, Pimm’s or the French aperitif Lillet (a key ingredient in James Bond’s famous Vesper martini), you’ve tasted quinine. It’s also found in Scotland’s “other” national drink, Irn-Bru, and in what is reported to be Queen Elizabeth II’s favourite drink, gin and Dubonnet – an aperitif which, coincidentally, was invented by a French chemist to make quinine more palatable for French troops stationed in North African colonies.

Quinine was eventually pushed aside in the 1970s by artemisinin, a drug derived from the sweet wormwood plant, as the world’s go-to malaria remedy. Still, the legacy of quinine runs deep around the world. Today, Ban-dung, Indonesia, is known as “The Paris of Java” because the Dutch transformed this once-sleepy port into the world’s largest quinine centre, brimming with Art Deco buildings, ballrooms and hotels. English is widely spoken in places as diverse as India, Hong Kong, Sierra Leone, Kenya and coastal Sri Lanka; and French in Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria today partly because of quinine. And in Spanish, there is still an expression that states, “ser más malo que la quina” – which roughly translates as, “to be worse than quinine”, a reference to the bark’s bitter taste.

At the height of the global “quinine hunt” in the 1850s, Peru and Bolivia both established monopolies over their highly lucrative tree bark exports. In fact, much of La Paz’s Neoclassical cathedral and many of the cobblestone streets running through the city’s plaza-filled historic centre today were built with cinchona bark, which at one point accounted for 15% of Bolivia’s total tax revenue.

However, the centuries-long demand for cinchona bark has left a visible scar on its native habitat. In 1805, explorers documented 25,000 cinchona trees in the Ecuadorean Andes. The same area, now part of the Podocarpus National Park, counts just 29 trees.

It is to plants that we owe some of the major medicinal breakthroughs in human history

Canales explained that the removal of quinine-rich species from the Andes has changed the genetic structure of cinchona plants, reducing their ability to evolve and change. Part of Canales’ work, in collaboration with the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew outside London, is to look at old cinchona bark specimens preserved in museums to study how human behaviour may have altered the plant. “We think that cinchona may have evolved to contain less quinine because of overharvesting,” she explained.

Recently, the World Health Organization halted studies of quinine’s synthetic descendant, hydroxychloroquine, as a possible coronavirus treatment amid safety concerns. Despite the fact that the drug is now developed in labs versus extracted from forests, Canales says the protection of the cinchona and the endangered “pharmacy of the world” that nurtures it, is crucial for the discovery of new drugs in the future.

In the absence of government protection of cinchona, local conservation groups are stepping in. Environmental organisation Semilla Bendita, literally “blessed seeds”, is planning to plant 2021 cinchona seeds for the 200th anniversary of Peru’s independence in 2021, and scientists like Schlagenhauf hope that more efforts to preserve the Andes’ biodiversity will follow.

“What the story of quinine shows is that biodiversity and human health go hand in hand,” Schlagenhauf said. “People often think of plant-based remedies as ‘alternative medicine’, but it is to plants that we owe some of the major medicinal breakthroughs in human history.

Credit: Source link