This is a tale of two December nights before Christmas – one on each side of the Atlantic – with visits by the ghosts of elections present, and elections yet to come.

Last Thursday, British voters handed their country’s Labour Party its worst defeat at the polls since 1935, setting off a round of soul-searching, angst, accusations and second-guessing.

A week later, and an ocean and a continent away, would-be presidential nominees of the US Democratic Party debated the direction for their party in Los Angeles, confronting many of the same questions that have vexed their UK counterparts, as they face their own rendezvous with electoral destiny next November.

‘I’m despondent’

Last Thursday, a crowd packed the Lexington pub in the London neighbourhood of Islington, not far from Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn’s constituency, to watch election-night coverage blasted on screens throughout the bar. An evening that began with cautious optimism for the largely left-of-centre patrons turned to shock, as exit polls indicated a Conservative triumph, and despair, as seemingly impervious Labour seats began falling like dominoes.

Blythe Valley was first, then Stoke on Trent, Bolsover, Great Grimsby, Wolverhampton, Wrexham and Workington. In all 27 seats that had been under Labour control for decades – the so-called red wall of the north – flipped to the Tories. The working-class backbone of the Labour Party had been broken, giving Conservative leader Boris Johnson a mandate for his policies and a comfortable majority to govern.

The only joy at the Lexington came when the televisions automatically turned off at midnight, prompting cheers for the momentary break from a bleak reality. They were quickly turned back on, however, and as the truth set in, everyone had their own explanation for what went wrong – and what it all meant.

A pair of Corbyn loyalists lamented what they considered to be a once-in-a-generation opportunity missed.

“We had a chance to have a socialist government, and it’s gone now,” one said, between long swigs of beer. “You’re damn right I’m despondent.”

Some didn’t quite see it that way, instead blaming Corbyn for pulling Labour too far to the left by backing policies like nationalisation of the mail, trains, power suppliers and private boarding schools, raising the national minimum wage, and instituting a four-day work week.

“I miss centre politics,” says Caroline, a 37-year-old account director from London. “I think the centre is where you capture votes. Instead, as the Tories have gone extreme right, Labour has gone to the left. And Tories are better at exploiting the fear of voters.”

Others said the defeat, while dispiriting, should not be an excuse to back away from hard-fought ideas and policies that are worth fighting for.

“There’s been a spark, and we need to nurture it and move forward,” said Joe Fenning, a 22-year-old jazz trombonist. “Even though this is a loss, you have principles, and we have to feel solid enough in those principles to stand by them and continue to work.”

Eli, a 20-year-old college student, attributed Labour’s loss to its mixed message on Brexit and call for a second referendum on whether the UK should withdraw from the European Union.

“A lot of the politics that Jeremy Corbyn espouses are politics I agree with and a lot of my family and community agree with,” he said. “The issue is being in the European Union.”

Rhodri Meredith, an 18-year-old engineer trainee, blamed Corbyn himself – and said he left his ballot blank rather than pick a candidate.

“I support a lot of Labour’s policies, but I just couldn’t bring myself to vote for him,” he said, citing Corbyn’s past praise of Sinn Fein, an Irish republican party, and allegations of tolerance of anti-Semitism within Labour’s ranks. “I know a lot of young people say you’ve got to vote for the policies, not the man in charge. But I couldn’t.”

In the days that followed, the kinds of conversations that took place at the Lexington were mirrored across the UK and in public forums. Some pundits and politicians cited Corbyn’s dismal personal approval ratings – as low as 21% favourable in one poll – as evidence that he was woefully ill-equipped to lead his party to a national election. Others focused on the battle over policies and priorities.

Corbyn himself, declining to immediately resign his leadership position, cited Brexit as the reason for the Labour defeat and stood by his left-wing proposals.

“I have pride in our manifesto that we put forward and all our policies we put forward that actually had huge public support on issues of universal credit, the green industrial revolution and investment for the future,” he said.

There were plenty of critics in the public sphere, however, who said it was those policies – and the message behind them – that were to blame.

“I think we need to think seriously now about, first of all, how you bring those lifelong Labour voters who felt that they not only couldn’t vote Labour but actually in many circumstances chose the Tories, how you bring Labour home to them,” Lisa Nandy, a Labour MP from Wigan and potential candidate for the party’s leadership, told the BBC.

“I also think we have to think seriously about how we rebuild that coalition that has propelled us into power three times in the last 100 years.”

A Democratic divide on display

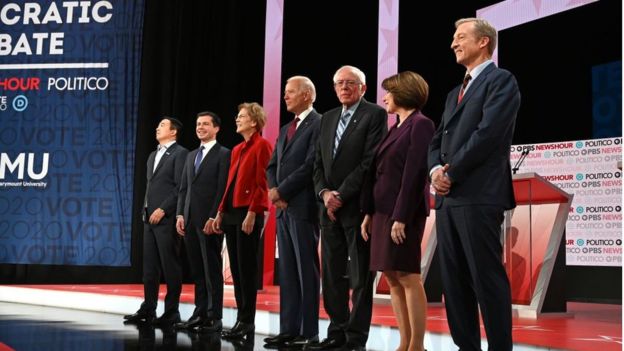

Fast-forward to the next Thursday and skip to the other side of the Atlantic, and the best way to rebuild a winning electoral coalition was also weighing on the minds of Democrat presidential hopefuls as they gathered in Los Angeles for their sixth candidate debate.

A divide within the party – between the progressives and the moderates – that has made itself apparent in nearly a year of campaigning was once again on full display.

On one side were candidates like Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, who said the path to victory was full-throated progressivism that could engage new voters and drive up turnout among the Democratic base.

“Let’s talk about how we win an election, which is something everybody here wants to do,” Sanders said. “You have the largest voter turnout in the history of America. And you don’t have the largest voter turnout unless you create energy and excitement. And you don’t create energy and excitement unless you are prepared to take on the people who own America and are prepared to speak to the people who are working in America.”

Sanders said the way to do this was with a “progressive agenda” that included government-run healthcare, a higher minimum wage, new environmental regulation, free university education and an across-the-board forgiveness of student debt.

While that may seem like weak sauce for dedicated Corbynites, a Sanders nomination with this kind of platform would mark the kind of decidedly leftward surge in the Democratic Party that Corbyn’s rise to the leadership in 2015 meant for Labour.

Meanwhile, the moderates at the Democratic debate made their own pitch for electability.

“We should have someone heading up this ticket that has actually won and been able to show that they can gather the support … of moderate Republicans and independents, as well as a fired-up Democratic base,” said Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar, touting her own electoral record.

“I think winning matters. I think a track record of getting things done matters. And I also think showing our party that we can actually bring people with us, have a wider tent, have a bigger coalition, and, yes, longer coattails, that matters.”

US moderates see a UK warning

While no one at the debate mentioned the UK general election directly, front-runner Joe Biden had already offered his opinion, putting himself firmly in the practical, moderate camp.

“Look what happens when the Labour Party moves so, so far to the left,” Biden said at a fund-raiser in San Francisco hours after the British results came in. “It comes up with ideas that are not able to be contained within a rational basis quickly.”

He went on to warn that if Johnson – “a kind of a physical and emotional clone of the president” – can win in the UK, Trump is a very real threat to win re-election in the US.

Highlighting this could be a savvy strategy for the former vice-president, given that Democratic voters, in poll after poll, say that their top priority is defeating Trump in the upcoming November 2020 presidential election – and a plurality of voters view Biden as the candidate with the best chance to do so.

He wasn’t the only moderate Democratic candidate to chime in about the UK results, however. New York businessman Michael Bloomberg said it was a sign Americans didn’t want “revolutionary change”.

And Pete Buttigieg, the South Bend, Indiana, mayor who has been surging in some early-state primary polls, told the Washington Post that the Conservative victory may actually be good news for Democrats, given that British Conservatives would be considered centre-left in today’s US politics.

“The climate policies, even a lot of the health and social policies that are considered more right or centre-right over there, are not at all welcome in today’s American Republican Party,” he said.

A kindred spirit no more

Progressives had once championed Corbyn as a kindred spirit to an American left that was becoming more influential with Sanders’ surprisingly strong challenge to Hillary Clinton in the 2016 Democratic presidential contest. Both benefitted from a vocal and engaged youth movement and called not only for a radical restructuring of what they viewed as entrenched corporate institutions, but also of their own party’s apparatus.

Sanders was a tonic for the Clinton dynasty, in this view, just as Corbyn marked a decided shift away from the Tony Blair years.

Labour’s surprisingly strong showing in the 2017 general election, even in defeat, was cited as evidence of the case. Sanders himself said that both he and Corbyn were taking on the “liberal elite” within their parties.

On the day of the UK election, US progressive standout Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez retweeted a video posted by Corbyn that derided income inequality and Conservative cuts to social programmes.

“This video is about the UK, but it might as well have been produced about the United States,” she wrote. “The hoarding of wealth by the few is coming at the cost of peoples’ lives.”

After the election, progressive politicians largely held their tongues.

California congressman Ro Khanna, who serves as a co-chair of the Sanders campaign, was one of the few with a public comment, saying that the Conservative victory showed that “nationalistic populism” was capitalising on stagnant working-class wages that result from globalisation and deindustrialisation.

“The task of the left is to offer an aspirational vision instead – how can we bring new, good paying jobs to people and communities left behind,” he said.

One election, two strategies

The debate – about the direction of the Democratic Party, as well as the relevance the UK general election could have for US politics – is far from over.

Will Marshall, president of the Progressive Policy Institute, a think tank that bills itself as “radically pragmatic”, sees some big takeaways for US Democrats from the British election.

“Economic radicalism or populism alone is not a winning hand for progressives,” he says. “Progressive parties ignore the new politics of culture and identity at their peril.”

He says Labour and the Democrats risk alienating voters if they focus on economic remedies and ignore the politics of cultural anxiety. Those politics – on issues like immigration, crime, terrorism and trade – animated support for Brexit in the UK and spelled disaster for Labour, and it’s what fuelled Trump’s rise in 2016.

“The British election confirms that 2016 was a political watershed,” he says. “It was not a year of political flukes. It marked the beginning of this dramatic realignment in which the new political divisions of culture, identity and geography have shoved aside the old left and right.”

Democratic strategist Avis Jones-DeWeever, on the other hand, cautions that it’s risky to draw too direct a comparison between Labour’s Red Wall that crumbled last week and the Democratic Blue Wall of mid-western industrial states that failed her party in 2016. The difference, she says, is demographics.

In 2016 Trump prevailed in places like Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin because turnout dropped and minority voters stayed home, she asserts. Put her fully in the be-bold, get-out-the-vote camp of the Democratic Party.

“The Democratic Party has a nasty habit of snatching defeat out of the jaws of victory,” she says. “The big way that happens is by playing small, playing safe, playing not to lose instead of to win.”

She says the way to win is to expand the base by turning out new voters, not fighting over voters who may have flipped from the Democrats to Trump and who may never fully come back.

“The future of making sure that this party wins is by making sure that they energise and maximise the vote. It’s disturbing to me that there is this fixation on wooing the white working class. If you want to win Pennsylvania, for instance, you’ve got to maximise the power of the black vote.”

Democrats – and their presidential candidates – will spend the months ahead hashing out these differences, in more debates and at the ballot box, as voters head to the polls in a string of primaries and caucuses starting in February.

Then, in November, they’ll face off against Donald Trump – and hope that the shock and despair on display at the Lexington pub last Thursday are only a pre-Christmas shadow of US elections that may be, not an accurate and irreversible prediction of those that will be.

Credit: Source Link