Pricking pain. Affliction. Twinging throbs that cause expectant mothers let out loud wails in delivery rooms.

Such was the case when Newszetu visited the baby delivery section of Mbagathi Hospital in Nairobi. Women were bawling and howling, some swearing words in between the yelps and some clamorously cursing the day they became pregnant.

That has been one reason women of the contemporary era prefer C-section deliveries, which help them reduce some anxiety of waiting for labour to start. But just because they have the option of an elective caesarean delivery doesn’t mean it is painless or it comes without risks.

Targeting to end painful labour for women, several remedies, including massage, hotpacks, water immersion, meditation, incense, aromatherapy, sterile water injections and even acupuncture, have been in use, but they have had varying results for different women.

“Childbirth is a joyous but painful experience for women. Labour pain is the mother of all pains”, it is said. But labour pain is different for each woman, and different for each pregnancy of the same woman. And no one can predict what your labour will be like. It can range from mild to extreme,” says Prof Sadhana Kala, a USA-trained robotic and laparoscopic surgeon at Uppsala University, Sweden.

While many women believe that the pain cements the bond between them and the baby, they also fear the side effects of medicated births and epidurals and decline even the painkiller injections that are usually given during labour.

But a new technique that uses Artificial Intelligence (AI) could end childbirth pain as we know it. The new technology means women would not need to carry a baby for nine months.

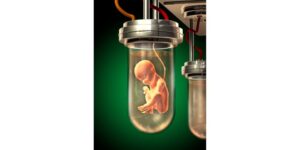

The creation of an artificial womb would have AI take care of the pregnancy for the whole gestation period after which the baby will be delivered to the mother.

But how is this possible? Isn’t this crossing an ethical border? Well, scientists who created the first artificial womb in 2020 say they are driven only by the desire to save the most vulnerable humans on Earth.

Emily Partridge, Marcus Davey and Alan Flake, neonatologists, developmental physiologists and surgeons who work with extremely premature babies at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in the US, say after three years of tweaking, their prototype is designed to give babies born too soon a greater chance of survival than ever before.

In 2017, they published their research findings in the Nature Communications journal explaining how they had found a way to gestate sheep foetuses outside maternal bodies, foetuses that would eventually become lambs no different from those that had grown in ewes’ wombs.

Their invention consists of a replacement placenta which comes as an oxygenator plugged into the lamb’s umbilical cord, which also removes carbon dioxide and delivers nutrients.

Blood is pumped entirely by the beating of the foetus’ heart, just as it would be in the womb. The bag acts like an amniotic sac filled with warm, sterile, lab-made fluid that the lamb breathes and swallows, just as a human foetus would.

This, scientists have predicted, could be replicated in humans, and help thousands of childless women enjoy motherhood for the first time ever while erasing labour from the childbirth process.

An artificial uterus or womb is a medical device that allows for extracorporeal pregnancy by growing a foetus outside the body of a mammal that would normally carry the pregnancy to term.

An artificial womb would need an outer shell or chamber to implant the embryo and protect it as it grows. So far, animal experiments have used acrylic tanks, plastic bags and uterine tissues removed from an organism and artificially kept alive.

Such a womb would also need a synthetic replacement for amniotic fluid, a shock absorber in the womb during natural pregnancy. There would have to be a way to exchange oxygen and nutrients — researchers would have to build an artificial placenta.

An artificial uterus might provide an optimum environment for the foetus to grow, giving it the appropriate balance of hormones and nutrients. It would also avoid exposing the growing foetus to external harms such as infectious diseases.

Once these are in place, scientists believe artificial gestation could one day become as common as IVF is today, a technique considered revolutionary a few decades ago.

It could be used to assist male or female couples in the development of a foetus. This can potentially be performed as a switch from a natural uterus to an artificial uterus, thereby moving the threshold of foetal viability to a much earlier stage of pregnancy. This could see the end of long-term hospital stays for premature infants.

Similarly interesting is how it could allow single men and gay male couples become parents without needing a surrogate.

But have we reached a point where humans can actively engage with and choose to utilise artificial wombs? A variety of legal and ethical concerns come to play.

One is the ‘14-day rule,’ law created in 1979 that remains in force in12 countries. It states that all research on human embryos must be limited to a maximum period of 14 days. This law was created in response to the birth of the world’s first successful in vitro fertilisation baby (IVF).

Though the rule has both scientific and moral implications, it was created with knowledge of what humans were capable of achieving at the time.

“But with the current advances in gestational and embryonic science, including work relating to artificial wombs, the rule seems practically obsolete,” says Dr Olga Adereyko, a general practitioner at Flo.

However, when Kenyan women learnt of the technology, divided opinion arose. On a Facebook engagement that this writer posted, Rubisky Kerry commented, “I saw this and I politely wanted to ask how much? Because this is the best invention ever!”

Maureen Achieng said she would be the first one on the painless baby delivery line. “Every time I think of giving birth, my body cringes. If I can’t withstand small period pains, what about labour pains? Yes to AI.”

For Miseda Winnie, a foetus should remain inseparable from its mother, from conception to birth. “No please, thank you. We must bond. There has to be a kick inside,” she said.

The implications of being incubated in an artificial womb were Felista Wangari’s concern, reminding scientists that once you create one solution, it comes with challenges.

“What do those in the normal womb get that they could miss in the artificial womb?

I’m thinking in the lines of cloning, genetic engineering and the things they missed that were discovered once the innovation was put into practice,”she observed.

The prospect of artificial wombs might offer hope for many, but it also highlights a number of potential hazards.

For some women, using an artificial womb for gestation to continue might seem like a welcome alternative to terminating a pregnancy. But there are fears that other women thinking about an abortion might be compelled to use an artificial womb to continue gestation.

Artificial wombs might also further increase the gap between the rich and the poor. Wealthy prospective parents may opt to pay for artificial wombs, while poorer people will rely on women’s bodies to gestate their babies. One critical issue of concern is the potential discrimination individuals born via an artificial womb may face. How can governments prevent discrimination or invasive publicity and ensure individuals’ origin stories are not subject to negative public curiosity or ridicule?

It might be easier to defend using artificial wombs in emergency situations such as saving the lives of extremely premature neonates. However, using them in other circumstances might need broader social and policy considerations.

But researchers are also studying the potential of using virtual reality (VR) to manage pain during childbirth.

VR technology offers simulated 360-degree experiences that look actual. VR, already popular for gaming but with limited applications in medicine outside surgical training, has been studied in recent years as a distraction therapy for reducing pain associated with blood draws in paediatric patients.

It has also been researched as ‘exposure therapy’ to help patients manage challenging symptoms associated with anxiety, phobias, and autism spectrum disorders.

“VR is a promising option, given the interest in non-drug pain management alternatives for childbirth. I suspect it will be studied more. And while I don’t expect VR headsets to be available at most hospitals in the near future, some patients might consider packing their own in their delivery go-bag,” says Dr Robyn Horsager, an obstetrics and gynaecology specialist at UT Southwestern Medical Centre.

It can influence the way users process pain by engaging the visual cortex and other senses, according to researchers from Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

During one study, researchers divided 40 women into two randomised groups, neither of which received pain medication during labour. Both groups included women who reported having moderate pain while their contractions were occurring at least five minutes apart.

One group received up to 30 minutes of VR. The other did not receive any intervention.

The women who used VR during labour reported feeling less pain after they began using the technology, researchers found. By contrast, the women who were not given reported feeling increased pain. They also displayed a higher heart rate.

Dr Melissa Wong, a maternal-fetal medicine sub-specialist at Cedars-Sinai, said despite its potential, using VR to help ease labour pain is one of the least looked at applications. “I think there is a tremendous opportunity to offer VR as another safe and effective option, and one that is medication-free, to help ease a woman’s pain during childbirth.”

VR could become a great tool for making childbirth more pleasant in the future as it can make the healthcare journey for patients more agreeable: alleviates all kinds of pain, dissipates fear, offers more empathy and better care.

But while early results are promising, experts say more research needs to be done before determining the actual benefit of VR with pain management in baby delivery.

Credit: Source link