Has any Champions League finalist been this much of an afterthought before?

The story of Saturday’s game is the last chapter of a so-far triumphant journey. To many, it’s a tale of the power of brute force spending: when you have (comparatively) unlimited money, when you push the limits of established rules all the way up to (and possibly past) their breaking point, when you have a decade to fine-tune the process without ever slowing down, perhaps you can control the uncontrollable. In a sport governed by the whims of a bouncing ball and just three or four goals per game, anyone can win — supposedly.

To a smaller subsection of fans, it’s a slightly different story with the same endpoint.

Manchester City‘s march toward just the second treble in English soccer history is powered by billions and billions of dollars, sure. But it’s the triumph of a club outside of the traditional hierarchy, a disruptor now winning all the games that the old rich would’ve been winning instead. Plus, plenty of other clubs have similar resources, don’t they? And none of them have taken down 100 points in a season, won five of six Premier League titles, or reached two of the past three European Cup finals — now have they?

But what about, you know, the other team?

For the unaware: the Italian club Internazionale are also playing in the Champions League final. Unlike City, they’ve won the thing before — three times — and a win on Saturday would tie them for the second-most European Cups since 2010. And yet, they’re not even the most popular club with the letters “Inter Mi-“ in their name this week.

While Saturday’s game in Istanbul seems like a culmination of one of the most dominant soccer seasons we’ve ever seen — and a jumping-off point for what that says about the future of the sport — there is another possibility. Inter Milan, the third-place team in Serie A, could also win the Champions League.

How big is the gap?

Does the gap in the magnitude of pregame narratives match the gap in quality between the two sides? The latter might be even bigger than we think.

Caesars Sportsbook puts the odds of City lifting their first European Cup at -500, while Inter are at +350. When you strip out the vig (the fee you’re being charged for them to place your bet), the implied probability of a City victory is 79%, with Inter down at 21%. To contextualize that, penalty kicks were converted 78% of the time across Europe’s Big Five leagues this season. A City win, according to the betting markets, is more likely than an undefended player kicking a ball past an immobile goalkeeper from 12 yards away.

If that seems like a pretty big number for a one-off game that is theoretically supposed to match up two of the best teams in Europe, it’s because it is. City are — by far — the biggest favorite in a Champions League final since 2010:

Those relatively shorter odds make sense. The Champions League field is limited to the theoretical best teams in Europe. While the pull-balls-from-a-bowl draw system and the knockout structure rarely match up the consensus two best teams in Europe in the final, the group stages eliminate most of the weaker teams, meaning there’s a pretty high floor for the quality of any team that could make it all the way to the end.

That’s unlike the World Cup or the Euros, where teams can’t acquire new players and are limited to whoever has citizenship. Plus, the group stages are much shorter, so this should lead to more randomness among teams that are also way more unequal than they are in the Champions League.

Well, not quite:

We can go further back, too. While odds to lift the trophy are hard to find prior to 2010, an economics professor at Boston University named Daniele Paserman — who also spends some of his free time trying to predict the outcome of soccer tournaments — looked at the odds to win in 90 minutes for every Champions League final since 2004.

“City are big favorites,” Paserman said. “Using the odds offered by various betting sites, one can calculate that their probability of winning the final in the 90 minutes is about 65%. The last Champions League final for which betting odds are available with such a large favorite was Barcelona–Juventus in 2015. Then, Barcelona’s implied probability of winning in the 90 minutes was about 60%.”

While they’re likely not as accurate a depiction of team strength as the betting markets, the Club Elo ratings go back all the way to the 1950s. They essentially award or subtract points to or from a team based on the quality of its opponent, the result and the score. Each match moves a team’s rating up or down slightly; a similar model is used to rank the best chess players in the world.

According to Elo, City are currently the fourth-highest-rated team ever — between two teams also coached by Pep Guardiola (Barcelona in 2012 and Bayern Munich in 2014) and Carlo Ancelotti’s Real Madrid in 2014. For their part, Inter are currently rated as the ninth-best team in the world — between Real Madrid and Newcastle United — and the gap between them and City is 182 points.

“Research done by Lorenzo Carli shows that this is the seventh-highest rating difference between finalists ever,” Paserman said. “One has to go back to the 1979 final between Nottingham Forest and Malmo to find a more lopsided final (345 points difference).”

There were structural differences that encouraged this kind of more extreme inequality back in the pre-1980s versions of the final. The main one: only the champions from each league were allowed into the tournament, which had no group stage and was straight knockout soccer from the jump. This kept out some of the best teams in the world and introduced much more randomness.

Since then, the tournament’s structure has grown to include many more teams and added in a six-game round robin phase that should tone down the randomness. But there will be a new kind of structural change at play on Saturday: the rise of the Premier League and the decline of Serie A. While Italy used to be the destination for the world’s best players, that all changed after the 2008 financial crisis, as most of the family-owned teams in Italy lost their spending power while the Premier League went in the other direction, with rapid commercialization of the league and the uber-rich foreign owners supercharging league-wide revenues.

City brought in more money than any other team in the world last year (big if: if Deloitte’s accounting is accurate). Inter, meanwhile, had revenues roughly equivalent to West Ham United, who just finished 14th in the Premier League.

So how could Inter win?

You’ve tried to cup water in your hands before, right? Maybe you were a kid in a bathtub; maybe you were an adult in a bathtub. Perhaps it was a pool, a sink, whatever. You’ve done it before, and according to one manager with experience across the Big Five leagues and the Champions League, therefore you have some sense of what it’s like to play against Guardiola’s Manchester City.

“If you can imagine cupping your hands together and trying to hold water: it starts to leak out a little — maybe in between two fingers, where they meet,” he said. “And so you start to cover that, but then it opens up another little gap somewhere else, and then water starts to go out there. Every time you try to adjust to what they do, they’re ready to adjust again. It’s impossible to hold them. It’s impossible to contain them with their movement and quality and fall movement and connections and timing.”

The inevitability of the difficulty, according to the manager, stems from the diverse talents of City’s two slightly more advanced midfielders: Kevin De Bruyne and Ilkay Gundogan. They’re both able to progress the ball up the field, carry it at their feet, play through balls, drift wide, play crosses, shoot from range or break into the penalty area — all in the same game.

“It’s a combination of incredible talent with incredible intelligence,” he said. “Those players are really clever about knowing when to go where and then how to connect everything.”

They can both execute with the ball in basically any situation, but they also both know which situations to enter. When there’s space in the box, they’ll break into it. When there’s the possibility for an overload on the wing, they’ll drift wide. When they need numbers deeper in order to progress the ball up the field, they’ll drop deep. And when they need to make a run to open up space for a teammate, they’ll do that.

“For me, Pep is the best,” the manager told me. “His tactics feed the top-level footballer better than any other tactical model that’s out there.”

The hard-to-replicate skills of those midfielders mean that City don’t have to be as aggressive in attacking space as soon as it appears in order to create goal-scoring opportunities. This allows them to be more patient with the ball, which means the opposition doesn’t have the ball and means that they don’t risk turning the ball over with too many bodies pushed forward.

This season, they play with essentially four “flat” centre-backs without the ball, but then John Stones (more skilled than just about any other centre-back out there) steps up into the midfield with the ball. But even with that wrinkle, they essentially still have three centre-backs behind the ball at all times, which makes them harder to counterattack than your average high-possession team.

Rodri is probably the best defensive midfielder in the world — always balancing the need to aid the attack with the necessity to snuff out a potential counterattack. Bernardo Silva gives them world-class defense on the wing and a similar all-around impact to KDB and Gundogan.

On the other wing, Jack Grealish is one of the best ball carriers in the world, which gives City the luxury of just sticking him out there without an overlapping full-back to combine with. And then, well, Erling Haaland doesn’t need to touch the ball; he just makes run after run off the back shoulder of the defense. This is possible because City’s other players are so good in possession that they need only 10 players involved to keep the ball as much as they do.

And, oh yeah: Haaland also gives them the ability to sit deep and just bomb balls long to him. Since they play so many defenders now, they’re better at defending deep than they’ve ever been before. And their keeper, Ederson, is better at bombing balls long than any other keeper in the world. Everything complements everything else.

How much of this was made possible by the 115 financial violations that they’re currently being investigated by the Premier League for? We might not ever know the exact extent, and that hangs heavily over the club’s success and Saturday’s match. But the result of it all, right now, can sometimes feel like something we’ve never seen before: a soccer team that doesn’t have to make any trade-offs and doesn’t have any weaknesses.

OK, so, to ask the same question again: How can Inter win?

Despite all of that, City are not invincible. They’ve lost six times this season and hell, the last time they were a massive favorite in the Champions League final … they lost to Chelsea, 1-0. So there are a couple of different ways Inter could do it:

1. Get lucky.

It happens all the time. One team dominates, creates a ton of chances but doesn’t score, and its opponent grinds out a set piece goal, scores on a counterattack, wins a sketchy penalty or holds on for 120 minutes and then takes the W in penalties. This is why we love soccer. This is why we hate soccer.

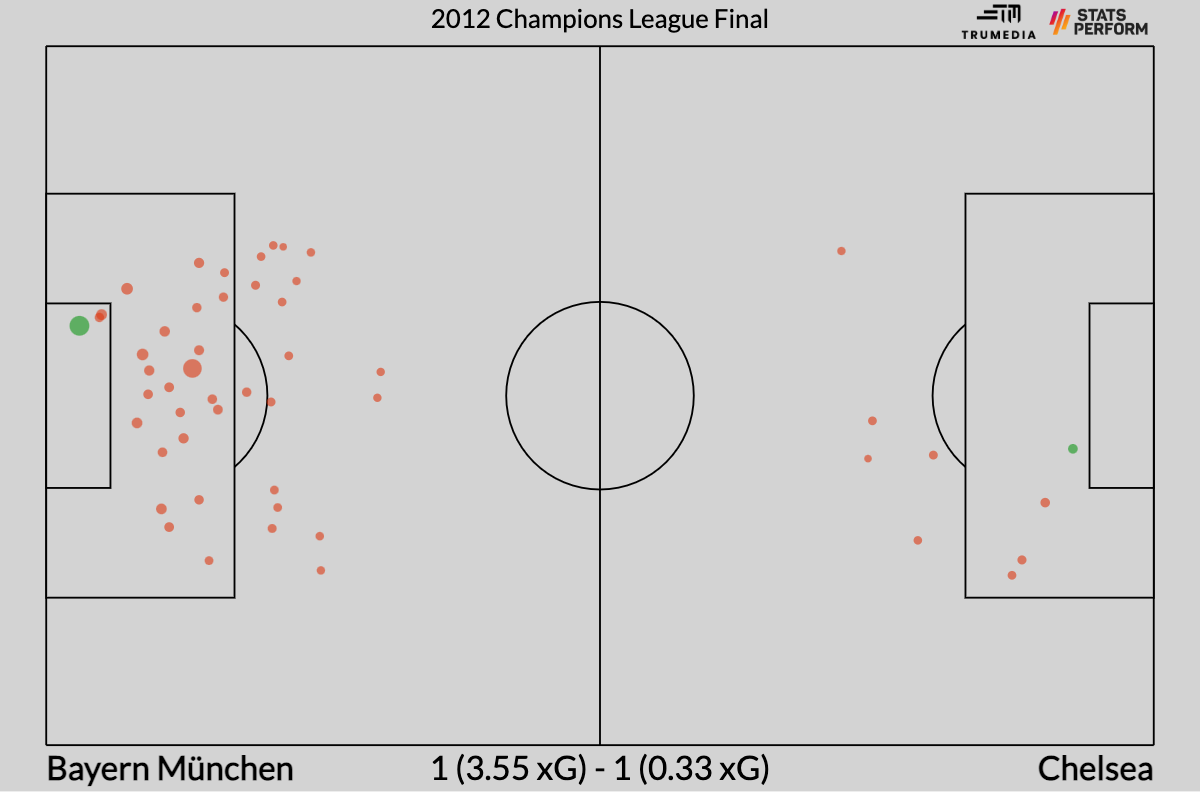

Per Stats Perform, which has data going back to the 2011-12 season, the most lopsided Champions League final was Chelsea vs. Bayern Munich. Bayern attempted 43 shots and generated 3.22 expected goals. They conceded nine shots worth 0.33 xG … and tied Chelsea 1-1 before losing in penalties:

You can’t really count on that happening if you’re Inter, but soccer is a fickle sport. Almost every shot is more likely to miss than it is to end up in the net. Sometimes you go 2-for-5 while your opponent goes 1-for-30.

2. Get hot.

Perhaps this should be an addendum to the first point, but I think it’s a decidedly different experience. In this version of a victory, you still get buried under a barrage of chances, but you limit the quality of the opportunities, counter a couple of times for high-quality chances and rely on your world-class keeper to bail you out, over and over and over again.

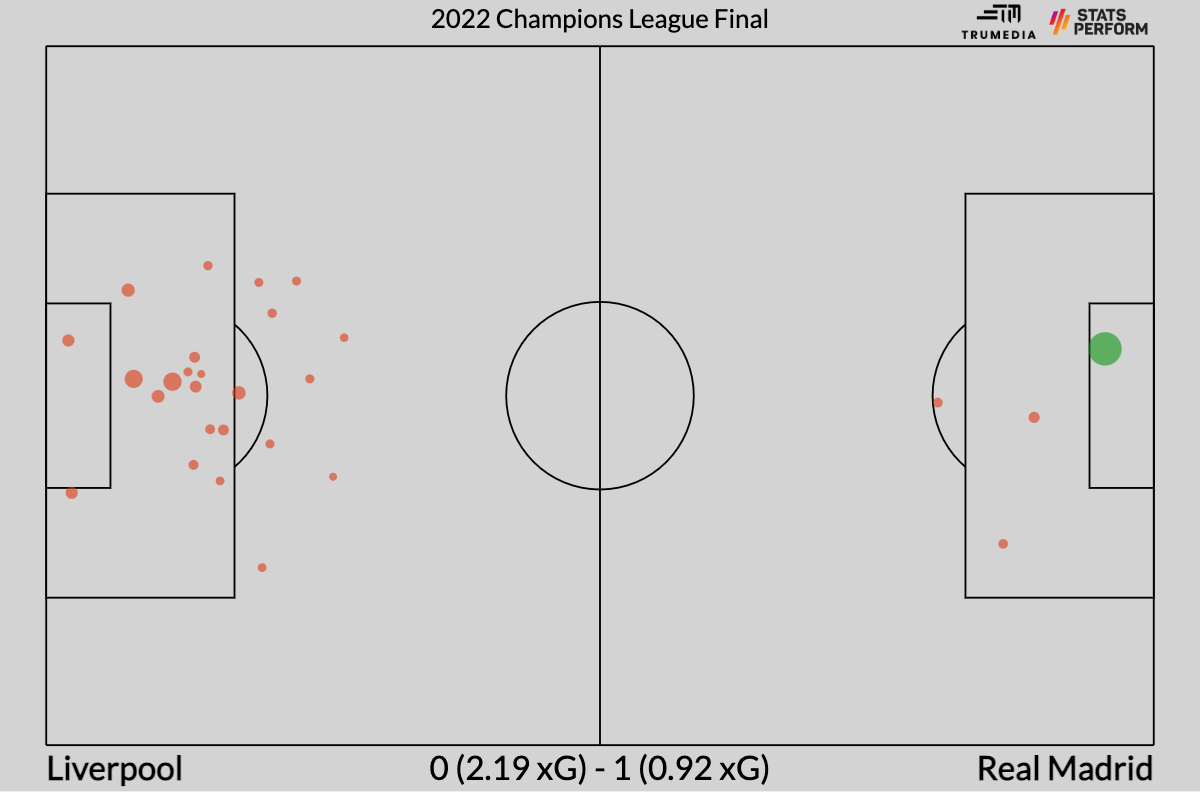

In other words, you do exactly what Real Madrid did to Liverpool last season:

Liverpool took a larger percentage of the shots (85.7%) than any other finalist in the Stats Perform database, and they generated nine shots that, based on where they ended up on the goal frame, would typically lead to 2.5 goals against an average keeper. Instead, Thibaut Courtois saved every single one, setting a Champions League final record in the process.

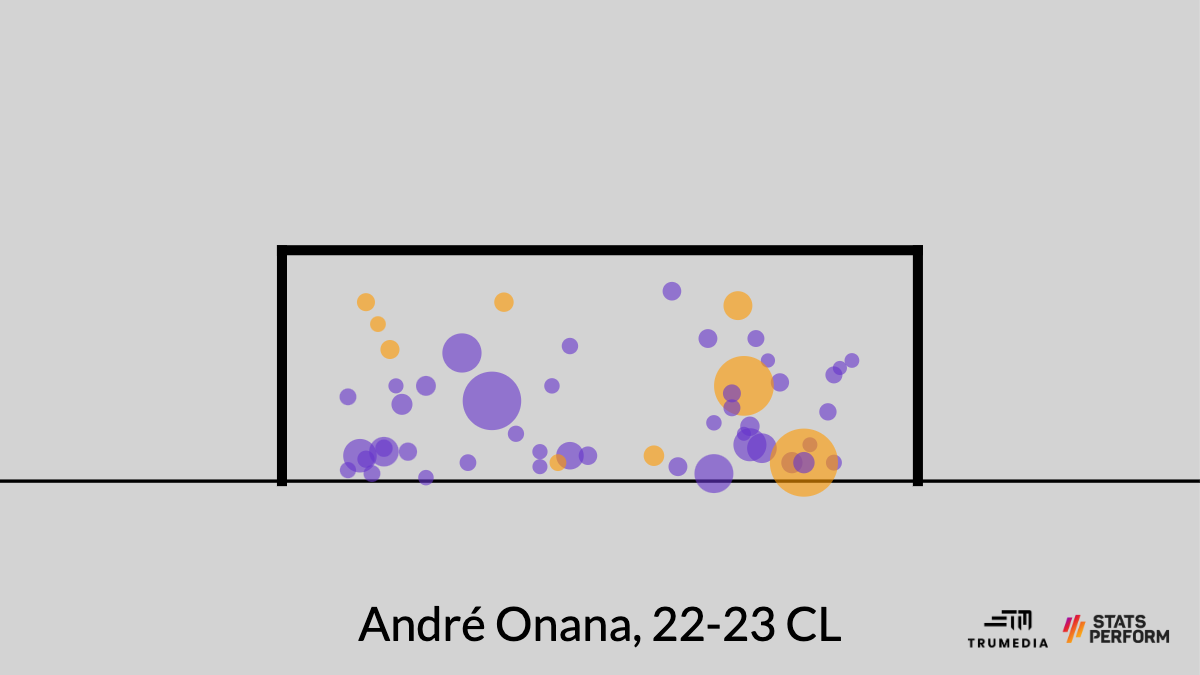

And, well, guess who has saved the most goals over expected in the Champions League this season?

Per Stats Perform, Onana was expected to concede 16.5 goals from the shots he’s faced in the competition so far this season, but he has conceded only nine (plus a 10th own goal). It’s really hard to envision an Inter win that doesn’t involve Onana standing on his head — but the good news for Inter is that he’s been standing on his head all season long.

3. Get weird.

Inter are weird. As my colleague Gabriele Marcotti pointed out a few weeks ago, this is true in two ways: manager Simone Inzaghi plays with two forwards, and he makes a ton of subs. Most notably, he frequently cycles out both of his forwards and both of his wingbacks.

In theory, this would allow the players who start the match to max themselves out physically if they know they’re not going to play the full 90. And it would allow Inter to get close to max physical effort from four of the 10 outfield slots.

The players themselves — outside of Lautaro Martinez, the team’s star — are all roughly similar in quality, so Inter aren’t really risking a sudden decline in performance by making the moves, either. And the positions aren’t ones that will drastically change the way a team plays, like a center midfielder or central defender — two positions that touch the ball a ton — might. It’s a really sound approach.

Most managers are too conservative with substitutions; players who are subbed on perform better than players who play the full game. And the logic is obvious: players who start the game will steadily lose energy, while subs get to come on with a full energy load and they get to play against guys who are tired. Inzaghi is taking advantage of a recent change in the rules — three subs to five — that no managers really seem all that interested in using.

In fact, for all his achievements as a manager, Guardiola might be the worst offender when it comes to eating his subs. Despite a deep and uber-talented roster, City made only 3.2 subs per game in domestic play this season — the second-lowest number of any team across Europe’s Big Five leagues. Inzaghi, meanwhile, made 4.9 changes per match — tied for the second most after Real Valladolid, who used up all their subs in every match.

The margin between these teams is massive, but the margins on which a single game is decided tend to be tiny. Could I see a match where Inter manages to keep City at arm’s length for 45 or 60 minutes, Onana makes a couple of big saves, Guardiola refuses to mix things up, and then Inzaghi’s forward and wingback subs make a difference against City’s tiring legs? I think this is probably the most likely path to victory.

But on top of the subs, Inter’s general weirdness might just make them hard to play against in a single game. Most teams don’t play with two strikers anymore, so when Inter do have the ball, City will be faced with a unique challenge, as their two centre-backs will be matched up man-to-man with two forwards. Normally, there’s just one centre-forward, plus the occasional midfielder running into the box, for the centre-backs to deal with.

Inter, though, have both. Although they play with three midfielders, they’re all attacking midfielders — or at least all used to be. A former No. 10, Hakan Calhanoglu is their defensive midfielder, while Nicolo Barella is a star in that Gundogan mold, and then there’s Henrikh Mkhitaryan, who, um, tries to impact the game in the same way. We’ll see how often they’re even able to get into these situations, but if Inter are able to advance the ball occasionally and take some risks when they do, City could struggle to deal with the two centre-forwards and then another midfielder breaking into the box.

Guardiola will no doubt be preparing for this, but the defensive rotations and responsibilities demanded by Inter’s unique setup and set of players will be different from what City are used to facing. Over a full season or even just a two-legged tie, they’d likely figure it out. But over one game? Maybe it causes some problems.

4. Get set.

Of course, the flip side is that Inter’s three attacking midfielders will have to deal with the most vexing part of playing against City: the movement of De Bruyne and Gundogan. Plus, the more times that Barella and Mkhitaryan break forward, the more opportunities City — and Haaland, in particular — will have to win the ball back and then attack into space. Given the demands of playing against those particular players in those particular spaces, perhaps Marcelo Brozovic, Inter’s stalwart defensive midfielder for the past half-decade, comes in to help deal with the challenge that Calhanoglu, in particular, has never had to face before.

A way to attack without risking instability, though, would be to capitalize on set pieces. Before a game against City, the manager told me that both defensive and offensive set plays take on an even greater degree of importance. Without the ball, you expend so much energy dealing with all of City’s movements and trying to track their rotations. Doing all of that right and then conceding a goal from a corner kick is basically a death blow to team morale, and it completely removes whatever tiny margin for error might’ve existed before it.

On the other end, you just know you’re not going to create many opportunities because you’re not going to have the ball and you’re also not going to risk too many bodies forward in open play. So, the few opportunities to draw up a play and create a situation where you have the advantage against Manchester City are invaluable.

As it happens, this is another area where Inter have been one of the best sides in Europe this season. Only 10 clubs generated more expected goals from dead-ball situations than Inter did. And per Stats Perform, 28% of the xG City allowed this year came from set plays — the second-biggest chunk in the Premier League this season. Of course, since they allow so few opportunities in general — 7.7 shots per game, the lowest mark in Europe by a full shot — they ultimately conceded only seven set piece goals across 38 Premier League matches.

Now, all of this isn’t to say that Inter don’t have lots of talent; they do. On aggregate, they’ve easily been the best team in Serie A over the past three seasons. And remember, they’re a top-10 team in the world, according to the results-based Club Elo model. But a top-10 team still doesn’t equate to anything close to where City currently are.

“Obviously at the highest level, you also have weapons, but in the end they’re just going to be better than you,” the manager said. So, how do you pull off the upset? When I asked, he laughed and then said, “You hope they have a bad day and you can nick one. I mean, that’s your best chance.”

Credit: Source link