HALFWAY ACROSS THE WORLD, in the country that thus far has stifled the coronavirus better than any, they’re playing baseball again. The games are intrasquad scrimmages. The players sometimes wear masks on the field. It is sports with a dystopian twist. And yet South Korea has pitchers throwing pitches and hitters swinging bats and fielders gloving balls, and the rest of the world doesn’t.

The fragility of it all isn’t lost on Dan Straily. He is 31 years old, a right-hander who for eight seasons pitched in Major League Baseball. In December, he signed a one-year contract with the Lotte Giants of the Korean Baseball Organization, a 10-team league that has served as an incubator for young talent and a proving ground for veterans seeking an alternative path back to the major leagues.

Today, the KBO is much more: a test case being watched by sports leagues around the globe. As seasons in almost all sports are postponed indefinitely, and as increasing numbers of people lock down to stop the spread of the coronavirus, Korean baseball is forging ahead with a plan to take advantage of its country’s thus-far-successful response. Exhibition games between KBO teams are scheduled to begin April 21. Following six preseason games, the regular season could begin.

Other leagues have had similar plans derailed. The Chinese Basketball Association delayed its scheduled restart. Nippon Professional Baseball in Japan paused its return after three Hanshin Tigers players, including star pitcher Shintaro Fujinami, tested positive for COVID-19. The same level of care in Korea that allowed the KBO to find itself in this situation — streaming intrasquad games on YouTube now, two weeks away from being the highest-level sports league in the world to play actual games — is also the greatest impediment to its return.

“If anybody, anybody — if the No. 1 starting pitcher to the person cleaning, security, R&D — anybody gets sick in that time, we postpone two weeks,” Straily told ESPN in an interview from Busan, South Korea, a city of 3.5 million where the Giants play. “We’ve got to make sure that no one else got sick.”

Little did Straily expect to be educating himself on the finer points of geopolitics and epidemiology when he flew from his home in Oregon to California to Australia, where the Giants would hold spring training, on Feb. 1. He joined a Lotte team that turned over most of its staff and emphasized familiarity with MLB. Among the new employees: Hank Conger, the longtime Los Angeles Angels catcher, who took a job as a catching coach; and Josh Herzenberg, a former scout and coach with the Los Angeles Dodgers and Arizona Diamondbacks, who joined as a pitching coordinator and quality-control coach.

The Giants returned from Australia to Busan in mid-March, two weeks later than planned, and were greeted by a culture that registered almost completely foreign to the Americans. Conger went into a bank without a mask covering his nose and mouth and was told by a security guard he wasn’t welcome. At Costco, Straily was stopped at the door so someone could wipe down his shopping cart and ensure he was wearing a mask before he entered.

“When we first got back from Australia, I thought the government was a bit overwhelming,” Herzenberg said. “Now I know I was wrong.”

TO UNDERSTAND WHY Korean baseball might return before any other organized sport, one must understand day-to-day life in coronavirus-times South Korea. It is a society that trades short-term personal liberties for safety, emphasizes public over self, rewards discipline and relies on functional government policies that value process and adhere to epidemiological tenets. It is why, regardless of KBO’s return date, it might not provide much of a road map for MLB: The United States has failed to replicate almost all of Korea’s institutional successes that allow the KBO to even consider playing again.

Preventing the coronavirus spread occupies every sphere of public life in Korea — a public life that has, to a reasonable extent, reopened with the number of cases flattening. South Korea witnessed a sudden surge in COVID-19 before the end of February but was able to significantly lower the numbers and minimize the spread by the middle of March. The nation averaged 658 new cases from Feb. 29 to March 5 but averaged only 99 new cases in a 25-day stretch from March 12 to this past Sunday. The U.S., by comparison, has witnessed almost a steady rise in the amount of new cases over that same stretch, from as low as 329 to as high as 34,196, reached Saturday.

As Herzenberg spoke from Busan late last week, he said 40 or so children were riding on bikes and scooters and playing on a plaza near the Giants’ stadium. They could do so because of the precautions taken around them. Upon the first positive coronavirus test in early February, the government ramped up testing capacity and quickly offered free, same-day testing stations around the country. Members of the Giants have been able to get tested and receive the results within 10 hours or less.

When someone tests positive, the government is authorized to scrape cellphone and banking data to get a full accounting of potentially at-risk locations. Text and social media blasts sent to large swaths of the population include the times, dates and locations of potential infection points. Following a 2015 outbreak of MERS that killed 36 and shut down thousands of schools, the government vowed to take measures well beyond those of a standard democracy in aiming to stem the spread of a potential pandemic. It is the macro complement to the micro inconveniences to which those living in South Korean have grown accustomed.

Hand sanitizer is ubiquitous. Masks are compulsory. Screen grabs from a recent Giants scrimmage went viral because it felt so unusual to see players and coaches donning surgical masks on a baseball field. The method was short-lived; the team scrapped the masks after a small handful of practices because the players found it difficult to breathe while playing. But even now, with the country endeavoring to return to normalcy, social distancing remains common. Before walking into most buildings, Herzenberg said, someone takes his temperature with a forehead thermometer. Those with high temperatures are not permitted in. At the Giants’ stadium, players and employees walk through a thermal camera that measures body temperature. Recently, a Giants player was feeling ill and ran a slight temperature, shy of 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

“Practice got canceled because it’s not worth the risk,” Straily said. “If someone wasn’t feeling well, he went to get tested for the virus and we all stayed home and stayed in our condos for the day until like 5 or 6 p.m. We got a text saying, hey, he’s completely fine. Just not feeling well, but he’s negative for the virus. So, you know, go get yourself some food outside your house finally.”

Getting to go outside is a perk to which Straily has grown accustomed. His wife, Amanda, who is a nurse, pointed out recently that Straily hasn’t been quarantined once. During the seven weeks the Giants spent in Australia, there was no stay-at-home order, and since they returned to Busan, he and Adrian Sampson, the former Texas Rangers right-hander, have explored the city cautiously, finding a barbecue spot and chicken joint and even a place for Straily to get his hair cut.

What the deal between MLB and the players’ union means for the 2020 season and beyond Jeff Passan and Kiley McDaniel

Straily is getting used to life in Busan, hoping he’ll be there for the remainder of the year. He has grown accustomed to the light that automatically switches on in on his condo if he walks too close to the door at night. He has plowed through the “get to know South Korea” PowerPoint presentation curated by Sung Min Kim — a former writer for FanGraphs and The Athletic who joined the Giants as a do-everything front-office official in the offseason — and Straily is transitioning to learning a new word in Korean every day. So far, all he has is annyeonghaseyo (hello), joh-eun (good) and kamsahamnida (thank you), but there’s time.

The differences are trivial. Straily still isn’t quite certain when an umpire is calling a ball or a strike. The Giants’ stretching routine takes adjusting to. A stiff bed caused Straily’s back to hurt, so Lotte got him a mattress pad. He had grown used to using a sauna while with the Miami Marlins, so the Giants bought one and are installing it in the clubhouse. The little things still register in South Korea because the pervasive fear of the coronavirus hasn’t paralyzed the country as it has so many others. And it informs the KBO’s approach: forward-thinking and exceedingly cautious.

“This is just my opinion, but I think the first thing they did was they threw the bottom line out the door and they were like, this is not about the money,” Straily said. “This is about keeping the people safe. This is about keeping our employees safe. It’s about keeping our fans safe and keeping as many people from getting sick as they could possibly control. And they’ve made us feel very comfortable to be here. I was pretty nervous to come to a foreign country during all this, and these guys have done an incredible job of making us feel comfortable, making us feel safe, since we got here.”

Straily regularly receives text-message updates from Min-Kyu Sung, the team’s new general manager who spent more than a decade with the Chicago Cubs and is overhauling a team that went 45-85 last season. Straily expects another soon, as every Tuesday the league meets with high-ranking team executives to inform them of the latest plans. The season has been pushed back multiple times already, so even with optimism and the lack of a positive test from a player, fear over what could be remains.

“Let’s say that everything does go good and we do decide to start the season,” Conger said. “What are you gonna do if a player on a team has it? Are you just gonna go ahead and shut down the season again or are you gonna try to isolate and quarantine him for two weeks? No one really has the right answer for it, so that’s the whole kind of uncertainty around everything.

“Yeah, we’re trying to get a timeline going to start everything. But it’s just tough because you don’t know what’s going to happen — you don’t know what’s going to happen if somebody gets it. What are you supposed to do at that point? Is there really a right answer about what to do baseball-wise?”

NO, ACTUALLY. THERE is no right answer. However much South Korea tries to control the coronavirus, until a vaccine is available, risks abound. It helps, Herzenberg said, that he’s in a country with a functional, robust response to outbreaks — and that baseball is a sport that almost naturally socially distances, with limited physical proximity let alone contact. He’s also aware that neither inures players, not when so many elements of baseball that are taken for granted are suddenly clear hazards.

“You go to your mouth, you go to your forehead, you touch your face constantly as a pitcher,” Straily said. “I don’t know why we do, but we do. The way things work here, one thing that’s like a little different, too: They don’t rub up the baseballs. The baseballs are basically pre-treated. So when they show up to you pearly white, they have a little bit of tackiness to them. They’re just not this smooth, glass-tabletop leather that they have in MLB. It’s got a little bit more than that.

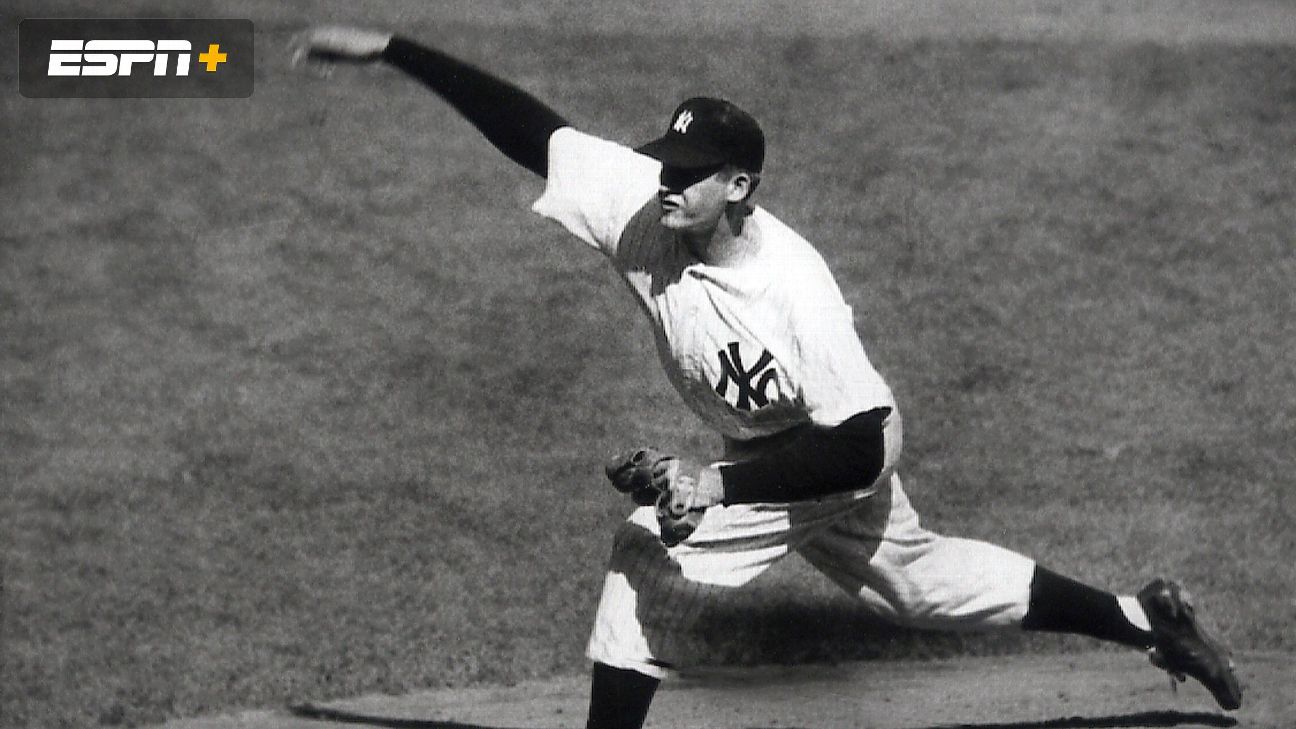

Relive 13 of baseball’s finest pitching performances: from Don Larsen’s perfect game in Game 5 of the 1956 World Series to Roy Halladay’s no-hitter in the 2010 NLDS.

“Basically the idea is that there’s no foreign substances needed. You have sweat and rosin and you have all the grip in the world that you need. So the baseballs haven’t been touched by seven people to get to you. They’ve been touched by the ball boy and the umpire, which is still two too many when you’re going to be touching your face in times like this.”

In times like this. Every moment is big, every decision consequential. It’s why Ji-Man Choi, the Tampa Bay Rays first baseman, chose to return to South Korea after MLB shut down spring training March 13 and postponed the season indefinitely.

“I made the decision to go back to my homeland for one because there’s no place to train in the States,” Choi said in an email. “My agent and I had tried to find a place but it seemed almost impossible. There was also the uncertainty of time frames. Problems like ‘how soon are we even going to overcome the coronavirus and play baseball’ made it easy for me to make a decision.”

Choi arrived in South Korea on March 24, eight days before the country ordered all incoming travelers to self-quarantine for 14 days. Choi imposed the restrictions on himself, remaining indoors even though the government allowed him to venture outside for groceries. In a couple of days, Choi will allow himself to begin working out on a baseball field again. He doesn’t know when MLB will return or what will augur the proper time. Conger wonders about baseball with fans, which in South Korea and MLB seems unlikely regardless of the differences between the countries. At one point, more than 60% of cases in South Korea were linked to a church in Daegu, and the size of crowds and proximity of fans in stadium settings concern medical officials, who say large gatherings are the greatest culprit for community spread, whether in South Korea, the United States or elsewhere.

“So just imagine: 15,000, 20,000 people one foot away from each other,” Conger said. “I know everyone loves sports and everyone wants to watch sports, but at what cost? Being one foot away from somebody, right now, even back in the States, you wouldn’t wanna be next to somebody even remotely close watching a ballgame.”

Straily thinks about these things, about his health, about the safety of his wife and son more than 5,000 miles away, about the world in which he lives now, which feels like a novel. Like Herzenberg, he sees kids playing outside the stadium, too, throwing balls around, riding on scooters, and it gives him hope. That and baseball.

The outspoken Reds pitcher talks with Jeff Passan about the future of baseball — MLB’s relationship with the players’ union, training during the shutdown and whether the game is too slow.

“I think it keeps me sane,” Straily said. “I talk to a lot of guys that are back in the States and they’re all curious, like, what are you guys doing, when are you guys starting, how are things going? A few of them had opportunities to come over here that chose to stay in America. And at this point, it’s looking like I made the right choice to come over here just for the simple fact that I’m playing and getting a chance to be out here. And, you know, not that we know for sure that we’re gonna play our season, but we’re pretty sure what’s gonna happen pretty soon. This is what I’m good at. Like, there’s one thing in the world that I’m good at. It’s playing baseball.”

So he works on his new curveball, the one whose grip he learned from 24-year-old teammate Se-Woong Park, whose thumb placement he refined using a high-speed Edgertronic camera and whose spin rate of 2,700 rpm could allow him to be the latest to develop a new pitch in Korea and return to MLB. He spends his days immersed in this, and in making sure the woman at the chicken joint knows that just because he’s American he can handle a little more spice, and in trying to make life a little more normal.

The truest arbiter of that for Straily, though, won’t be seen in South Korea.

“I hope there’s baseball in America because that means that things are doing much better,” he said. “I think that’ll be a big sign that everything’s going in the right direction, that everyone can stay the course but take a deep breath when there’s that announcement that, hey, Major League Baseball is going to start on this date. Even if there’s no fans allowed. I don’t think any fans at this point would be upset about that.

“Once it’s announced that, hey, baseball’s coming back, that it’ll be a great sign that things are heading in the right direction because it’s not going to be allowed until they are. So my big hope for this whole thing is that we get baseball soon.”

Credit: Source link