The Great Wall of China, which winds for 21,000km across the north of the country, is one of humanity’s most renowned creations. It has been listed as one of the “new” Seven Wonders of the World alongside the Taj Mahal and the Colosseum. It was named a Unesco World Heritage site in 1987. When tourists come to Beijing, they head by busload to the wall’s most famous outposts.

Few of them come here.

The Jiankou section of the wall ribbons over the top of jagged green mountains for 20km. From the valley below, it looks like icing piped onto each peak.

It is located just 100km north of Beijing. But it is completely different from its better-known neighbours, like Badaling or Mutianyu. There is no souvenir shop or Starbucks, no cable car or gondola. No one is waiting to sell you tickets. No one is there to make your visit easier, either: to access this section of the wall, you must hike 45 minutes up a mountain.

And there was – until recently – no restoration. Built in the 1500s and early 1600s, this section was left untouched for centuries. Around seven kilometres of it fared especially badly. Over time, the towers melted into mounds of rubble. Some parts of the wall tumbled down completely, rendering once-wide sections so narrow that only one person could walk at a time. Trees and bushes pushed through the ground, making the wall look more forest than fortification.

The lack of work on the wall made it picturesque, but dangerous. “Every year, maybe one or two people die hiking on this part of the wall,” said Ma Yao, project manager of the Great Wall Protection Project at Tencent Charity Foundation, which funded the latest repair. “Some from hiking and falling down, dead. And some from being hit by lightning.

The technology helped us to repair the wall as traditionally as possible

In order to prevent further tragedy – and to preserve the Jiankou wall for future generations – restoration began in 2015. This intensive phase, focusing on a 750m-long section, wrapped up in 2019.

On a sunny spring day towards the project’s end, I sat on the wall with Ma. We were surrounded by fortification-topped peaks as far as the eye could see. “You can see the mountains here. The machines can’t come here. We have to use people,” he told me. “But we should use technologies to help these people to do this work better.”

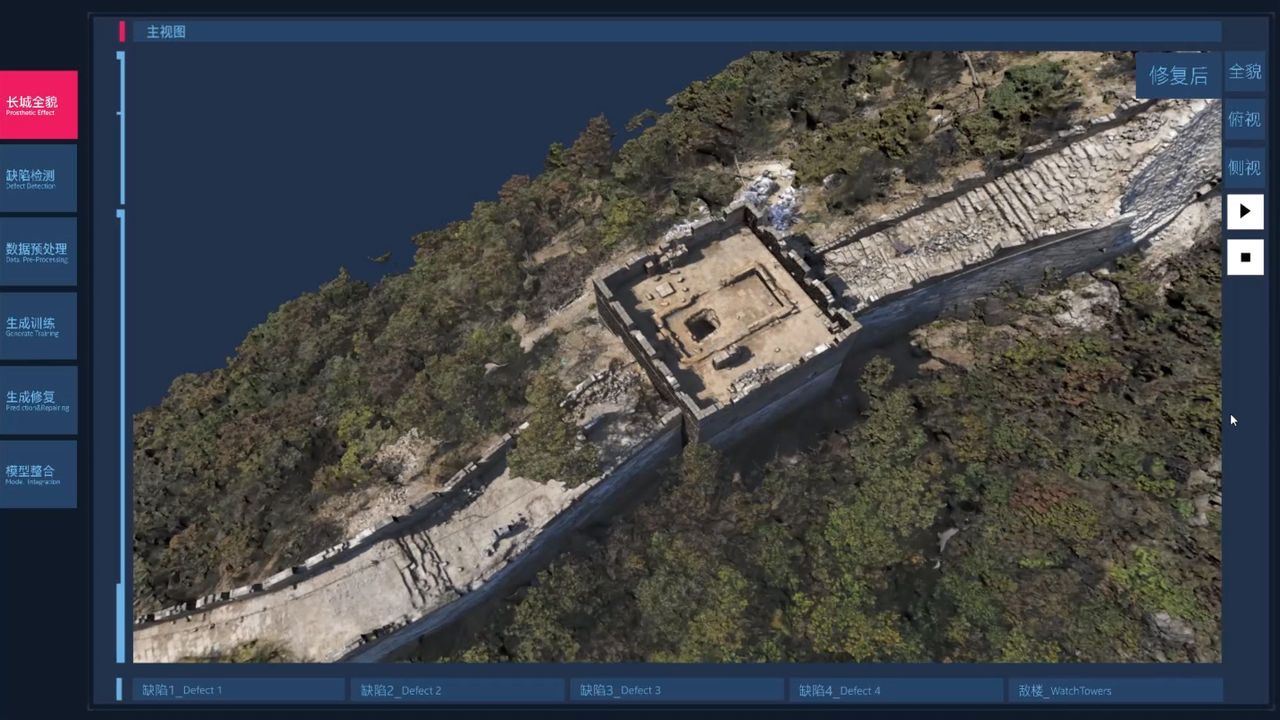

For the 2019 phase of the project, that technology included drones, 3D mapping and a computer algorithm that could tell engineers whether they had to remove that tree or fix this crack – or whether they could safely leave them as they were, reminders of when the wall had once been wild.

“The technology helped us to repair the wall as traditionally as possible,” Ma said.

Snaking across northern China, from Manchuria to the Gobi Desert to the Yellow Sea, the Great Wall is vast. Its history is equally epic: it was built over more than 2,000 years, from the 3rd Century BC up to the 17th Century AD, by 16 different dynasties.

The longest and most famous section belongs to the Ming dynasty, who built (and rebuilt) the wall from 1368 to 1644, including the Jiankou section. An archaeological survey by the State Administration of Cultural Heritage and the State Bureau of Surveying and Mapping calculated that the Ming wall ran for 8,851km – including 6,259km of wall, 359km of trenches, 2,232km of natural features and 25,000 watchtowers. Far from one line from A to B, the network includes loops, double walls, parallel walls and spurs.

Today, about one-third of the original Ming fortifications have vanished. Only about 8% are considered to be well preserved. The threats have been many: natural erosion from wind and rain; human destruction from construction; and even people selling bricks. And, of course, the damage caused by footfall. That’s true even at Jiankou, despite having so many fewer visitors than stretches like Badaling.

“Just over the hill there are 20 million people,” said historian and conservationist William Lindesay, referring to Beijing. “So, the ‘leave nothing but footprints’ [advice] – even footprints can actually damage the wall.”

Lindesay has devoted his life to researching, writing about and fighting for conservation of the wall. Originally from England, Lindesay saw it on a map as a boy in 1967 and decided he had to explore it. In 1987, three years after a run of Hadrian’s Wall that inspired him to revive his childhood fascination, he walked the Great Wall on foot. He was the first foreigner to walk the Ming wall from end to end, an undertaking he did again, albeit by Jeep, in 2016. “It wasn’t this scenic footslog. I was stopped by the police nine times – you could call them arrests,” he told me. “I was eventually charged with repeated trespassing in closed areas and I was deported. So, I went to Hong Kong and [was later able to come back in]. I had the physical adventure, the political adventure – and I made three proposals of marriage to the same girl, so I had the romantic adventure.”

“How did that turn out?” I asked.

He laughed. “Very well. We celebrated our 33rd wedding anniversary three weeks ago.”

[It] actually constitutes the world’s greatest open-air museum

He also fell in love with the Jiankou wall: the contrast of the grey fortifications against the green mountains; the trees growing through the bricks. He moved to the foot of Jiankou with his family in 1997 and coined the term “wild wall” to describe the difference between a spot like Jiankou and the reconstructed, touristed sections like Badaling. “The wild wall – and there are thousands of kilometres of it – actually constitutes the world’s greatest open-air museum,” he said.

His library is dotted with photographs from his long treks. Every surface is laden with books on the wall, many of them written by him. He showed me some of the treasures he’s accumulated over the years: a 16th-Century “rock bomb”, hollowed out to hold gunpowder; a polished crossbow that’s a reconstruction of the kind that archers shot from the wall in its earliest days.

In the more than 20 years since moving here, he has seen the Jiankou wall degenerate. At first, he said, he would have classified the section as well-preserved. Not anymore. Where the wall steps were perfect, they’ve now been gouged out by footsteps. Towers have crumbled. The wall has become more dangerous to climb.

“You can’t make the Great Wall forbidden. It’s almost an impossible task. So, I think the government has had no option but to start to reconstruct and stabilise, for safety,” Lindesay said.

He paused. “I love the wilderness wall,” he said. “But when the visitor levels reach a certain level, it doesn’t work. Then it becomes a tragedy.”

The hike up to the wall passes through orchard, then forest. The path is punctuated with the occasional sign that pleads for preservation. “Chinese civilisation belongs to the world and everyone has a responsibility to protect the wall,” says one. “Take nothing but photos, leave nothing but footprints,” says another. I hiked up and back down again every day for four days, and only once did I run into other visitors in the forest: two women who I heard long before seeing them. One was singing a folk song. When they saw me, they insisted on a selfie together. There are not many American travellers in these parts.

At the top, the repair project came into view before the wall itself did. A mass of scaffolding rose up before me. After several months, the final phase of the project was coming to an end.

“The wall is a fortune and legacy for all of us,” said Zhao Peng, the restoration’s lead designer. “Repairing it and protecting it is not merely something we’re willing to do, but that we want to do – and it’s also a responsibility.”

But repairing the wall can be opposed to protecting it. If a site is rebuilt too much, it can lose the flavour of what it once was. Many say that that was the fate of Badaling, the most popular part of the wall. During its overhaul, which started in the 1950s, it was rebuilt with new bricks, sandwiched together with modern cement. Many today are covered in graffiti. It’s been derided as a “Disneyfication” of the wall, a contemporary imagining of what once had been.

The Jiankou restoration was planned to avoid those mistakes.

Now, I watched as a team of mules waited patiently near the scaffolding. They’d come up the same way I had, laden with enormous sacks of white ash. One of the workers mixed the ash into a thick white soup. There would be no modern concrete here. Other workers spread the mortar onto bricks with a trowel, placing them carefully into the wall.

The 750m section that was the focus of this phase climbed up the hill before me. A few trees rose through the bricks. It was a far cry from the forested path that Jiankou had been before. Still, plenty of hints of wildness remained.

As I climbed up, one part was extremely steep and slippery, so much so that even in hiking boots I had to crab-walk to avoid falling. In another, the side of the wall had slid away completely. And at the end of the section, the wall just – stopped: it turned into a chute that tumbled down the mountain so steeply you couldn’t possibly survive the journey without climbing ropes or an abseil.

Minimum intervention doesn’t mean no intervention at all

Zhao pointed out the various interventions that had been made. Despite Lindesay’s concerns about footfall, the single biggest cause of damage to the Jiankou section is water erosion. Long-term, keeping the wall preserved meant changing the water flow from rainfall. The team introduced drainage holes and other channels for the water to pass through. And in sections where water tended to accumulate, they used new bricks – these were denser, so the water couldn’t penetrate, and flatter, so it could move. The new bricks look noticeably different from the old ones, a way for future generations to tell the difference between the original and the restoration.

“We have one principle – that is the minimum intervention principle,” Zhao said. “But minimum intervention doesn’t mean no intervention at all.”

One of the ways that the project minimised its intervention was with modern technology.

Normally, Zhao explained, designers would do a detailed inspection and survey of the wall and note any weaknesses . Back in their studio, they would work out how to manage those limitations to preserve the wall for the future.

This time, they were aided by something new. In Beijing, at Peking University’s School of Archaeology and Museology, engineer Shang Jinyu took me through the process. His team flew a drone over the section, taking around 800 images in a half a day. Using those images, they were able to build a detailed 3D model of the wall, down to every brick and crack. To get a complete picture of the restoration, they repeated the process halfway through, and again at the end.

“We have done many 3D models and panoramic photos like this in different heritage sites in China,” Shang Jinyu said. “But it’s the first project where we can use the system as part of the restoration project, and can combine it.”

That data helped inform how the design team would repair the wall with minimal intervention. One example is a crack on one of the towers. “This crack is hard to inspect by manual labour,” said Zhao. “By flying the drone, taking photos and then digitising the data, we are able to decide the size of the crack, how much the wall is tilted and pushed out. We then can decide how stable the wall is.”

The data also provides a clear record of each restoration stage. “The main goal of the 3D is to monitor the whole repair process,” Ma said. One example was one of the towers. Its roof was covered in trees, which were uprooted to keep the tower intact. To remove the trees, the team had to remove the bricks.

In the past, it would have been difficult to know how to replace the bricks with any precision. Now, they could imitate the original placements much more closely, leaving bricks out where they’d originally been missing.

“They repaired the top of the tower, but it still looks like something that’s been standing there for hundreds of years,” Ma said.

Interestingly, the Peking University team wasn’t the only one to have this idea. The computer and technology behemoth Intel did their own 3D modelling – their drone captured 10,000 images – and shared their version with the China Foundation for Cultural Heritage Conservation, which was involved in the restoration project, too.

Both projects were, largely, a proof of concept. Their data wasn’t incorporated as early, and as much, as it could have been. Still, they showed the construction and design teams just how the new technology could help them work faster in the future, and with less intervention.

Now, the teams are taking this knowledge into the next phase: restoration of a different part of the wall. “It’s in Xifengkou, about 300km from Jiankou,” Ma said. “The section is about 900m. And some of it is underwater.

“Like at Jiankou, we’ve used 3D modelling. And based on the experience of repairing the Jiankou section, the team adjusted some of their plans for the restoration because of the results of the modelling.”

It was lunchtime on my last day at the Jiankou wall. Chubby ants marched across stones. A furred bee as big as my thumb lolled past. It’s as if everything here was super-sized, epic, like the wall itself.

In the shade of one of the towers, the workers slept. Their days began with a hike up the mountain at dawn. While drones and 3D modelling might have helped their design team, it didn’t replace the labouring work using chisels and hammers.

The silence was broken only by two couples in hiking gear; the women had bandanas pulled up to their eyes to protect their skin from the sun. “Don’t go that way,” they told me, panting. “It’s too steep.” They gestured to a nearby section. A part of it had fallen down creating a sheer drop. Unless you were an adept free climber – like one of the builders, who I saw scramble up it like he was taking a stroll – the only way to the next part was by taking a dirt path around the side.

No one seemed bothered by the two white signs with crisp red strokes that said, in Mandarin, “NO TOURISTS”. Technically, the wall isn’t officially “open” to the public, although no one can clarify exactly what that means, or explain why other signs aimed at tourists dot the hiking path.

With the restoration finished, it’s likely that this tranquillity will change. The “NO TOURIST” signs probably will, too. There will be less fear of the wild wall. More and more people will come, not only the most intrepid.

The wall may be less derelict and dangerous than it once was. But it remains a striking reminder of the centuries that shaped not only the fortification, but China itself. And its spirit, if a wall can have a spirit, still has whispers of wild

—

Filmed by Michelle Gao and Amanda Ruggeri

Reported, presented and produced by Amanda Ruggeri

Translations by Michelle Gao

Edited by the BBC Travel Show

With thanks to the Tencent Charity Foundation, China Foundation for Cultural Heritage Conservation, Intel and Peking University’s School of Archaeology and Museology

Credit: Source link