Not that long ago, Christian Pulisic did everything.

Among Premier League wingers and attacking midfielders in the 2019-20 season, the Chelsea and U.S. men’s national team star did all of these things at an above-average rate, per the site FBRef: took shots, created chances for his teammates, passed the ball into the penalty area, received the ball inside the penalty area, pressured the opposition in the attacking third, dribbled past defenders, carried the ball forward, passed the ball forward, received passes forward, drew fouls, nutmegged opponents, won penalties and won headers.

As an American soccer player, Pulisic was facing a special kind of the impossible expectations that all star athletes face — and, somehow, he was meeting them. Unlike, say, his former Borussia Dortmund teammate and uber-prospect Jadon Sancho, he couldn’t afford to fail. If Sancho didn’t become one of the best players in the world; the English national team would be just fine. But even with Pulisic electrifying opponents in CONCACAF, the United States missed the 2018 World Cup. The future of the national team seemed to hinge on Pulisic, who was already the best player to ever wear the USMNT jersey, getting even better.

And he would … right? RIGHT?

This is the story of Pulisic’s progression, and regression. What’s he doing with the ball, what’s he doing without it and what’s next?

I imagine it’s hard for non-Americans to understand the bizarre neuroses that come with supporting the USMNT. When Pulisic moved from Borussia Dortmund to Chelsea for more than Liverpool paid to sign Mohamed Salah, the reaction in the United States was not, universally, one of “It’s amazing that one of the best teams in the world is finally willing to pay that much money for an American soccer player.” No: there was also a not-insignificant subset of observers who wondered, “Hm, is this the best move for his career? What if he doesn’t get enough playing time?”

When you view European soccer through the lens of the USMNT, you behave something like a distant stage-parent, attempting to optimize the un-optimizable developmental paths of a group of 20-somethings who live at least an ocean away. Although fans are looking at each player in terms of what they mean for the national team’s chances of succeeding in a tournament that happens once every four years, the players just don’t do that. They’re living their lives and creating their careers in an inefficient and illogical market for players, trying to get paid as much as they can and find whatever sort of professional fulfillment they’re looking for. What’s best for them often isn’t best for the national team.

Except, with Pulisic, it was. He was so good that it didn’t matter. His career path didn’t need to be optimized because almost every soccer team in the world seemed as if it would be better with Christian Pulisic rather than without him. In his first start after the 2019-20 season was paused due to the pandemic, he was the best player on the field in a 2-1 win against Manchester City. A few weeks later, he was the best player on the field against the about-to-be-crowned Premier League champs, Liverpool. And a few weeks after that, he was the best player on the field in the FA Cup final, scoring the opener against Arsenal before injuring his hamstring in the 49th minute.

The first half of last season was a wash for everyone at Chelsea, and although he wasn’t an automatic starter under Thomas Tuchel, Pulisic was, once again, the best player on the field against Real Madrid in the first leg of the Champions League semifinals in Spain. He won the Champions League and followed that by scoring the winner in extra time against Mexico in the CONCACAF Nations League final. And then came this season.

It’s not just that he has barely played, but even when he does play, he isn’t doing much of anything.

What’s happening on the ball?

First, let’s go through what has disappeared.

To start, he’s not shooting much at all. In 12 Premier League appearances for Chelsea this season, Pulisic has attempted 12 shots. Per 90, he’s attempting 1.43, which puts him in the 19th percentile for players at his position in the Premier League. He’s down from 2.23 shots per 90 last year and 3.25 shots the year before.

If you’re gonna make an impact for one of the best clubs in the world with so few attempts, you have to make up for it by creating a ton of chances for your teammates, right? But Pulisic is doing even less of that. He’s creating 0.06 expected assists per 90 minutes — all the way down in the 5th percentile among players at his position in the Premier League. That’s down from 0.15 xA/90 the year before and 0.18 the year before that. He’s creating under one chance per 90 minutes.

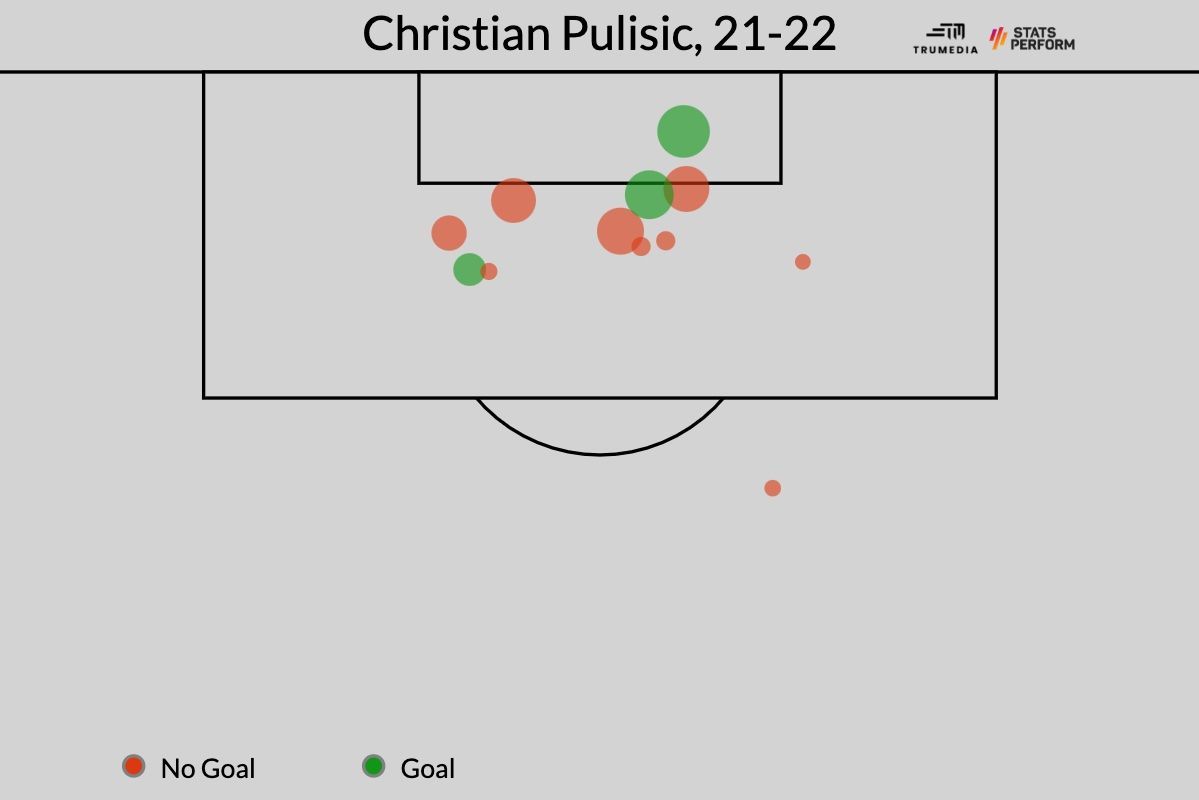

In terms of the two things clubs pay their attackers big money for — taking lots of shots and creating them for your teammates — it’s been grim so far. However, Pulisic has made up for the decline in shots with the quality of his attempts. He’s attempting shots from closer to the goal than any other winger/attacking midfielder in the league: just 10.1 yards away, on average.

With the increased quality, he basically has maintained his non-penalty xG output from last season — 0.29 npxG per 90 this season, 0.28 last season — but that’s still a big drop-off from the 0.43 of his first Chelsea season.

You know what’s also gone? Those driving runs that left everyone breathless when he first burst onto the scene with Borussia Dortmund and the USMNT.

You know what’s also gone? Those driving runs that left everyone breathless when he first burst onto the scene with Borussia Dortmund and the USMNT.

In his first season with Chelsea, Pulisic completed 10 progressive carries per 90 minutes. (The definition, per FBref: “Carries that move the ball towards the opponent’s goal at least 5 yards, or any carry into the penalty area. Excludes carries from the defending 40% of the pitch.”) That dropped down to 8.86 last season, and it has fallen even further this season, to 5.95, which is right about league-average for his position.

If you squint hard enough, though, you can see a common maturation happening. As dribble-heavy players get older, the ones who become stars tend to dribble less often, replacing that dribbling with better off-ball movement and passing. The ones who don’t are the ones who plateau and never develop beyond all the initial excitement they generated when they were embarrassing defenders in their teenage years. Pulisic isn’t dribbling anywhere near as much as he used to, but he’s getting on the end of better chances than he ever has before.

He’s certainly a different kind of player this season. Analyst Michael Imburgio created a model called DAVIES that uses data from FBref to value the on-ball actions of players and to classify them into player types based on where they touch the ball and what they do with it. The three types of attackers are “dribblers,” “playmakers” and “finishers.” On average, dribblers are both less valuable and younger than the other two categories.

In Pulisic’s first four seasons for which the model has data, it saw him as a “dribbler.” This year, it shifted him to a “finisher.” This also tracks with the formation change to a back three enacted by Tuchel when he took over midway through last season; with wing-backs occupying the wide areas, Chelsea’s wide attackers now function much more like second strikers or attacking midfielders.

Although it’s a new role or an evolution or more likely a bit of both, it’s not necessarily better. In Pulisic’s first season at Chelsea, the DAVIES model saw him adding 0.41 expected goals per 90 minutes with everything he did on the ball. It dipped to 0.27 last season, and this year it’s down to 0.21, his lowest mark in the model’s dataset.

“Finishers usually get most of their value from shooting (shot volume, shot-on-target accuracy and npxG) and getting on the ball in the box,” Imburgio said. “Despite the revised role, he’s not doing either of those things any more than he was last year [his ratings for those two are almost exactly the same]. He’s also contributing less in buildup, less with dribbles, and his key pass/xA/general shot creation numbers have dropped off. So the change is a net loss. If he’s really a ‘finisher’ now, he should be in a position to improve his shot production and get on the ball in the box more to compensate for the drop-offs, but he isn’t doing that.”

It’s not all about the ball

Despite his ability to glide past defenders and drive possessions forward, what really made Pulisic special at the club level was his ability off the ball.

Top teams like Chelsea don’t really need Pulisic moving the ball up the field for them or breaking down defenders too often. It helps, sure, but these teams have world-class midfielders, full-backs and center-backs who have no problem moving the ball into the attacking third or finding players inside the box. Instead, they need attackers who know how to move off the ball in the most crowded area of the field. And with Pulisic on your team in previous years, you had a winger with the physical ability and anticipatory skills to get on the ball in the box as often as your central striker. Even when he didn’t get on the ball, his movement in the penalty area constantly created gaps in the opposing defense.

Some of this shows up in the on-ball data. He’s getting such high-quality shots because he understands how to move inside the penalty area. Although his touches in the penalty area haven’t increased as he has drifted higher and further infield, he’s still in the 81st percentile for his position for that statistic. He’s also receiving 9.05 progressive passes per game — more than last season, and good enough for the 92nd percentile of the Premier League.

His two best moments of the season showcased this skill. In the World Cup qualifier against Mexico on Nov. 12, he senses a cross coming, shifts toward the penalty spot and then darts across the face of the defender to head in the winner. It’s a nice ball in, but the main reason this goal happens is because of what Pulisic does without the ball:

Then, for the equalizer against Liverpool on Jan. 2 — easily his best game of the season — he recognized where the space behind the opposition backline would be and exploited it for a goal.

You can see the moment he sees the space present itself — before the ball even gets to N’Golo Kante — and then he takes off and times his run perfectly. Again: it’s a nice pass, but the goal doesn’t happen without the recognition of the potential opportunity and the run to take advantage of it.

However, these examples (and the aforementioned stats) only account for the times when Pulisic receives a pass. What about all the runs he makes when he doesn’t receive the ball? The ones that open up space for his teammates? That’s all absent from Pulisic’s paltry-looking on-ball numbers.

Using tracking data from broadcast streams gathered by the company SkillCorner, Twelve Football created a number of metrics that aim to quantify how players move off the ball.

Founded by math professor and author David Sumpter, Twelve has an app and also provides consulting work to clubs. Sumpter’s team looks at

- “target runs,” which are runs when a player receives a pass

- “disruptive runs,” when a player makes a run but the pass goes elsewhere

- “potential runs,” when a player makes a run and a pass is attempted to him but isn’t completed

- “space creation”, the value of a run if a teammate had completed a pass to him

They also track “sprints” and “high-speed runs,” the latter of which is just a slightly slower version of a sprint.

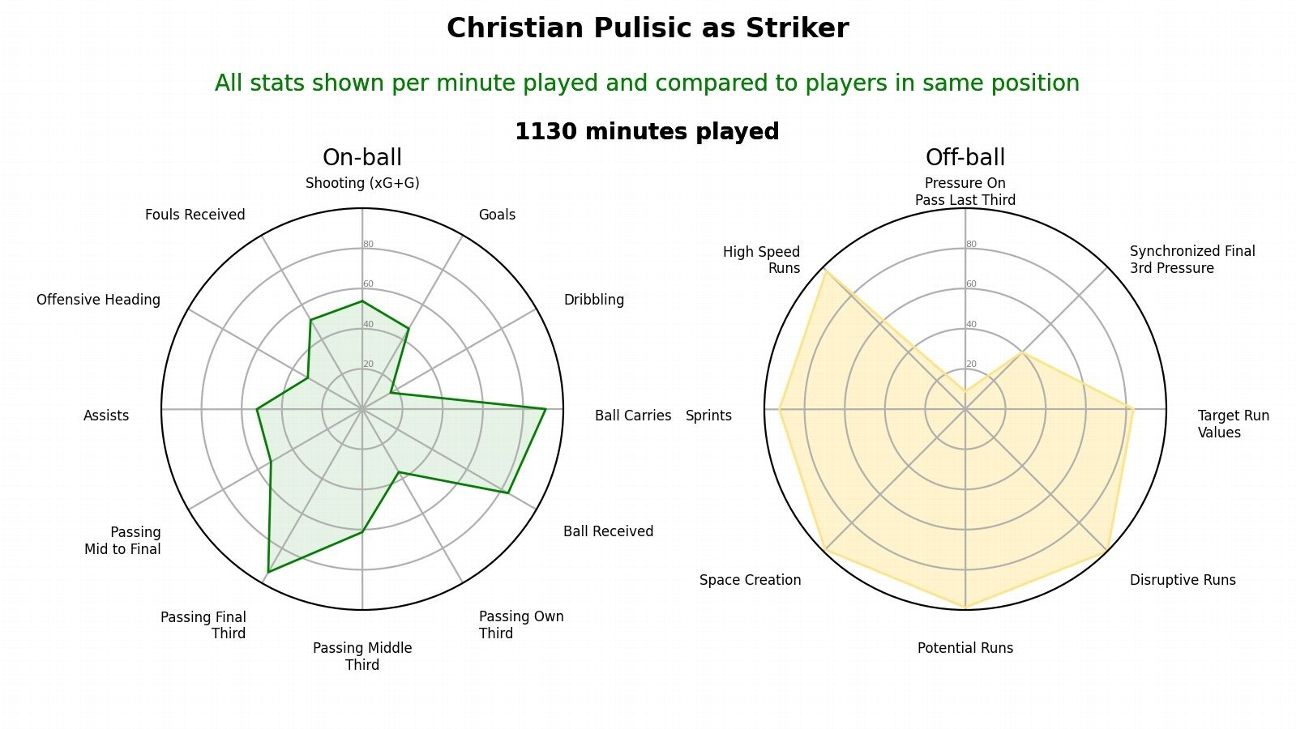

Last season, Pulisic’s off-ball movement was as valuable and as frequent as that of any player in the league. He was an absolute menace when another Chelsea player was in possession. His off-ball numbers are on the right, while the radar on the left shows how much value he added through various on-ball actions, per a model similar to Imburgio’s.

Each circle represents a different ranking percentile:

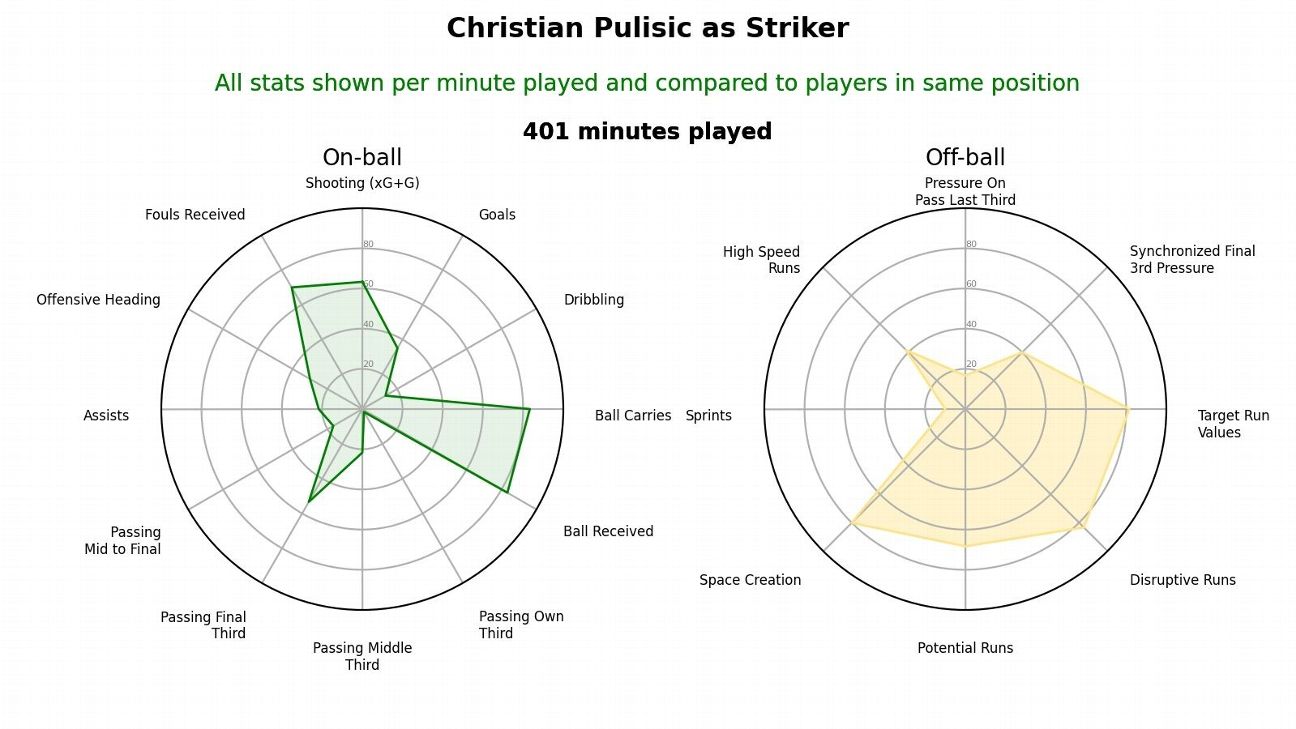

With even less on-ball action this year, perhaps Pulisic has been even more dynamic off the ball, dragging defenses up and down the field, opening space for Chelsea’s other attackers to shine? Unfortunately, that just hasn’t been the case. He’s way less active off the ball, too:

With even less on-ball action this year, perhaps Pulisic has been even more dynamic off the ball, dragging defenses up and down the field, opening space for Chelsea’s other attackers to shine? Unfortunately, that just hasn’t been the case. He’s way less active off the ball, too:

It’s a limited sample of minutes, and he’s still in the 80th percentile or above for space creation, targeted runs, and disruptive runs, but look at the massive drop-off in sprints and high-speed runs. He’s just simply not running anymore.

It’s a limited sample of minutes, and he’s still in the 80th percentile or above for space creation, targeted runs, and disruptive runs, but look at the massive drop-off in sprints and high-speed runs. He’s just simply not running anymore.

What comes next?

It’s really hard to look at all of the above and come away with any conclusion other than: he’s dealing with the effects of being hurt so often.

Per the site Transfermarkt, he has missed 42 games in his first two-and-a-half seasons with Chelsea. Most recently, he was out from the beginning of September through the end of October with an ankle injury picked up in the qualifier at Honduras. He tested positive for COVID-19 last summer. There was the hamstring injury in the FA Cup final, and he also tore an adductor muscle in January of 2020. Throw in a 2020-21 season that was condensed due to the coronavirus pandemic, a Champions League final run, a pair of Nations League games and a bunch of World Cup qualifiers halfway across the world and Pulisic’s only real extended time off has come from, well, getting hurt and not being able to play.

That’s not recuperation time or recovery; it’s a rehab grind to get your body back to the point where it can sprint as much as it used to. He’s been playing soccer or rehabbing from soccer-related injuries for nearly three straight years at this point.

On top of that, he’s a 23-year-old living in Europe in the middle of a pandemic. He gets paid well, but not well enough to isolate him from the anxieties and stressors of the past two years. He has talked openly about his mental health and the increased pressure he has felt playing for the United States. Playing for Chelsea can be stressful, too; they’re constantly bringing in big-money attackers, seemingly regardless of positional need or past performance of current players, and the coach changes all the time. They’re the one consistently successful big club in the world that operates under constant volatility.

And so, this is really the first bad season of Pulisic’s career. He’s not playing much for Chelsea, and he’s rarely playing well when he does play. With the USMNT, it often feels as if he’s trying to do the things he doesn’t do at Chelsea anymore — taking a ton of touches, dropping deep, dribbling at defenders left and right — even though he’s most effective doing what he did against Mexico: finding space and making runs in the box.

Despite that, he still isn’t even in his prime yet. His development had been linear, up to now, but soccer players rarely progress in a straight line. Players who have played as much as Pulisic has by age 23 — and played as well and for clubs as good as Borussia Dortmund and Chelsea — just turn into stars more often than not.

This season is concerning, especially the physical decline, but it still makes up just a small percentage of a much larger and much more impressive sample of play. He needs to figure out a way to get his legs back, or, if injuries and the grueling schedule have forever sapped him of some of his burst, he needs to find new ways to contribute toward winning soccer.

History suggests he will, but for the first time in his career, Christian Pulisic has given USMNT fans a reason to worry — not that they needed one.

Credit: Source link