In a year of startling upheaval for the aviation industry, one seismic change, at least, had already been predicted.

For years, China has been en route to become the world’s biggest aviation market, eclipsing the United States. The International Air Transport Association predicted it would happen by 2024, but it seems the Covid-19 crisis has fast-tracked the takeover.

China snatched the crown of largest country market in May 2020, according to data from aviation analysts OAG, and, while the US sputters, IATA now says that China “continues to lead the global recovery of aviation activity.”

This aligns well with the country’s “Made in China 2025” strategy, which aims to bolster domestically designed and manufactured products. For China’s aviation ecosystem, this means less reliance on buying foreign airplanes.

Underpinning this transition is a huge migrational shift of China’s workforce towards urban centers, which, at least before the pandemic, was generating a burgeoning demographic of middle-class consumers with higher disposable incomes and an insatiable appetite for air travel.

As of the beginning of this year, more than 200 extra airports were scheduled to be built in China over the next 15 years to cope with the relentless growth spurt. And, not so long ago, Boeing’s 2019-2038 Commercial Market Outlook was saying that China would require 8,090 new passenger aircraft deliveries plus associated support services over the next 20 years — a market that Boeing estimated as being worth $2.9 trillion.

Meanwhile, transportation dots are finally being joined up across the country’s vast expanse, helping to drive the extraordinary scale of China’s infrastructural ambitions.

“China has become criss-crossed with direct domestic air routes,” says Cristiano Ceccato, director of Zaha Hadid Architects, the firm behind the recently opened Beijing Daxing International Airport.

“This fine-grain reticulum of connectivity mirrors China’s High Speed Rail network and reflects the exponential growth in need for small and medium-sized airliners which can satisfy the traveling public’s demand for safe, fast and inexpensive means of travel.”

International airliner with Chinese character

The latest analysis by IATA estimates that global passenger traffic won’t return to pre-Covid-19 levels until 2024.

Against that backdrop, China is likely to remain a strong power against a weakened United States and Europe as they face ongoing lockdowns and travel restrictions due to new localized spikes of the coronavirus.

As aviation tentatively reboots, Boeing and its European rival Airbus are duking it out for the lion’s share of the recovering market with their B737 and A320 airplanes respectively — a dynamic that’s contingent upon Boeing resolving its 737 MAX woes.

Meanwhile, China has developed — and is now at the stage of flight testing — a homegrown contender, the COMAC (Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China) C919.

All three competing aircraft have comparable specifications. They’re all single-aisle, twin-engined aircraft with a seating capacity for between 150 and 180 passengers (depending on class configuration) and are suitable for servicing domestic and regional routes — exactly the flight envelope of the bulk of China’s aviation networks.

“The COMAC C919 is designed to be an ‘international airliner with Chinese characteristics,'” says Ceccato. “This means an ability to match the quality and safety established by Boeing and Airbus, but also by incorporating the specific needs of the Chinese market: High-density, high-frequency missions with fast turnaround times from airfields with broadly varying levels of development.”

The C919 has a range of up to 5,555 kilometers and has garnered a running total of 815 orders from 28 customers, predominantly Chinese airlines. That could put a serious dent in the order books of their incumbent suppliers.

At a time when many Western carriers have been parking their planes in the desert and deferring or canceling airplane deliveries from manufacturers, COMAC’s order book was boosted by the formation in February of OTT Airlines, a new China Eastern Airlines subsidiary.

The plan is that OTT will be a launch customer for the C919, with the carrier operating on trunk and regional routes, focused around the Yangtze River Delta region and radiating out towards the surrounding provinces.

But what sets the COMAC plane apart from its Western rivals in terms of the in-flight experience?

The French connection

While the major elements of the airplane such as the nose, fuselage, outer wing, vertical stabilizer, horizontal stabilizer and movable surfaces have been independently designed by COMAC, the company has enlisted Western expertise, notably that of French high-tech industrial group and aero-engine manufacturer Safran, which is producing the aircraft’s cabin and nacelles (the structure that houses the engines and connects them to the wings).

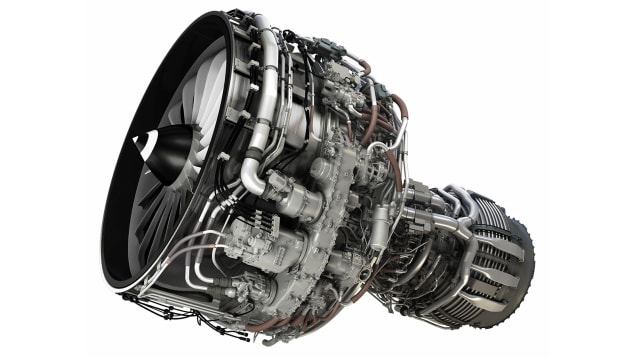

The C919’s LEAP-1C engines are being produced by CFM, a joint venture between US engine-maker GE Aviation and Safran.

Subsidiary Safran Cabin says it will supply the lavatories, galleys, and cockpit doors for the C919. The company told CNN that “the lavatories are larger than what is now commonly seen on competing aircraft.”

That will be welcome news for passengers forced to do contortions in modern airplane toilet compartments.

More spacious lavatories would mean it would be possible to move around with less contact with surfaces, and it could also make cleaning and maintenance a less onerous task for the crew that scramble on board between flights to disinfect the toilets — a boon in the Covid era.

Larger restrooms aren’t the only difference. The back of the aircraft will feature a full-sized galley with ample space for the flight crew to work. Safran says it “recognizes that many of its airline partners based in China will fly these aircraft on short routes within China, which makes meal service a challenge.”

To address the compressed flight times on domestic routes, Safran says its cabin designers have come up with an “ergonomic galley design, with large work surfaces, equipped with easy-to-maneuver ‘Hybrite S trolleys,’ which help the crew get meals, snacks and drinks out to passengers quickly.”

Spacious galleys are also likely to be a selling point worldwide as airlines work towards complying with new inflight catering guidelines set out by the Airline Catering Association (ACA).

For reasons of heightened food-handling standards introduced in response to the pandemic, airlines are now switching to touchless on board food service. This means a lot more packaging, which in turn means a need for extra gallery space. The C919’s galleys conveniently tick that box.

Carbon footprint

As for environmental concerns, Safran says it “has made advancements in its composite structures which enable interiors to be both lightweight and durable, helping to reduce carbon footprint while withstanding the rigors of short-haul service.”

The aircraft’s engines are also claimed to be more efficient. The CFM LEAP-1C engine, which was selected by COMAC as the sole Western engine option for the C919, offers “a 15% reduction in fuel consumption and CO2 emissions versus current engines, and up to a 50% margin on NOx emissions,” says Safran. The engines will also mitigate noise in and around the airports where the C919 operates.

Safran’s involvement in the C919 program is hardly surprising. The company has been trading with China for over a century and has formed strong ties with the leading companies in the Chinese aviation industry, and today supplies all the major Chinese airlines.

It also has established specialized maintenance and repair facilities with major Chinese airlines such as Air China and China Eastern Airlines.

COMAC has built a fleet of six prototype versions of the C919 that have been pacing through flight testing programs.

The first prototype made its maiden flight in 2017 and the most recent publicly declared flight test took place, despite the Covid-19 crisis, in February 2020, when prototype AC106 took off and landed at Dongying Shengli Airport.

Although the test aircraft are clocking up the air miles, no official date for the C919’s first entry into passenger service has been announced. Speculation about time frames has proved, in the past, to be optimistic. When first launched in 2008, the program had slated 2014 for a first test flight, but this slipped to 2017.

Late 2021 or early 2022 is now being mooted as a possibility for commercial operations, but a mix of factors could impede that.

The outcome of the US elections could influence America’s deteriorating relations with China — either for better or worse, which in turn could have ramifications over the export of CFM engines.

CFM partner GE Aviation recently, as reported by CNN, “dodged a bullet” by being granted permission to export the LEAP 1C to China, despite US national security concerns that the engine technology could be reverse-engineered.

Then there’s the broader context of the ongoing pandemic, which has bludgeoned public inclination towards nonessential air travel.

There’s also the question of whether a new narrow body entrant would have sufficient market demand while there’s a glut of unused short-and-medium-haul airplane capacity parked, airworthy and ready for reactivation at short notice. Attractive deals on nearly new 737s and A320s is a distinct possibility — a consequence of airline fleet cutbacks.

Finally, on a technical level, the COMAC C919 flight test regime and associated certification for airworthiness could be delayed due to unforeseen glitches that are part and parcel of developing any new type of airliner.

Clearly, Comac’s C919 still has some way to go, especially in uncertain times. But if successful, longer term, a third option for aviation’s short- and medium-haul market, as air travel emerges from the pandemic, could significantly redistribute the balance of power in civil aviation.

Credit: Source link