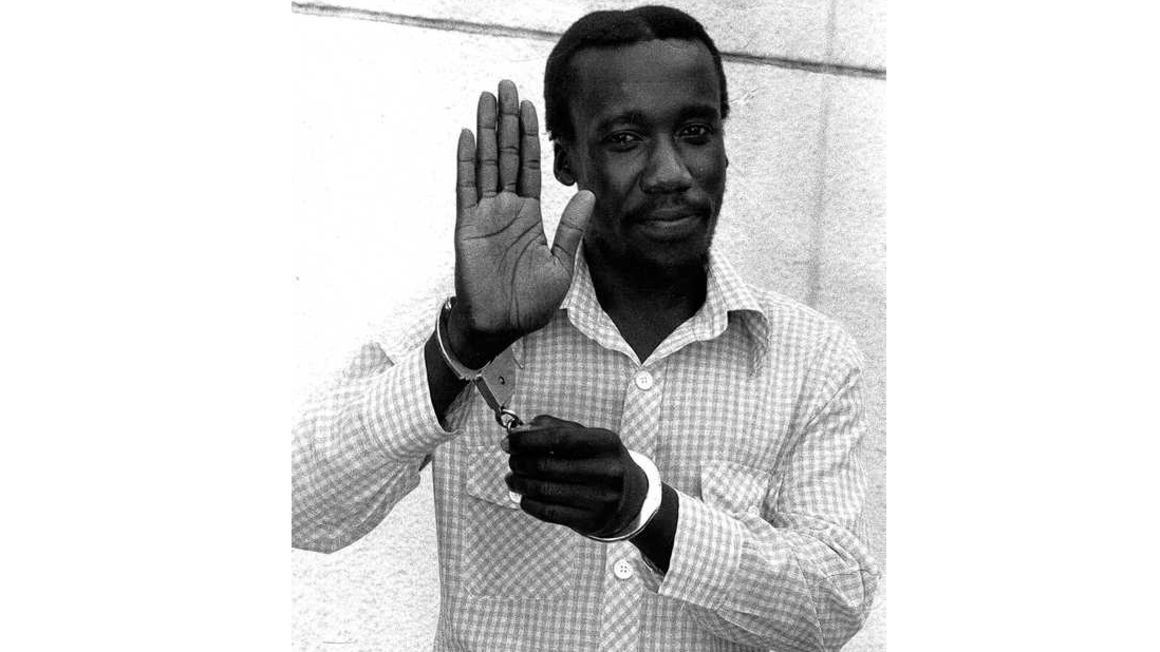

Somewhere in an unmarked grave behind the high walls of Kamiti Maximum Security Prison lie the remains of Hezekiah Ochuka. Kamiti is the place where Kirugumi wa Wanjuki used to hang condemned people before Kenya lost the stomach for that practice.

The story of how Ochuka’s attempt to overthrow the government of President Daniel arap Moi failed and took him straight into Kirugumi’s hands is now well known in Kenya. Less analysed is how it fundamentally affected the course of the country’s political development and life in general.

After Ochuka’s execution, his body wasn’t given back to his family, and although no official reason was ever given, the thinking behind such an action is easy to make out. After the oftentimes violent episodes in any country’s life, graves of people like Ochuka can become shrines of worship and magnets of inspiration for people disaffected with the government.

People who court martyrdom, even when to the objective observer their plans – like Ochuka’s – are a cocktail of ambition, foolhardiness and incompetence. They have a habit of attracting deep public sympathy, and in death they become icons.

Even the greatest of political actors are never able to compete with the power of the dead and they try to neutralise its appeal by always paying homage to the memory of the heroically fallen. But it is easier done when the dead are out of sight and reach.

History is written by winners, and as far as Kenya’s goes, Ochuka is not one of them. He lies in an unmarked grave as a criminal who committed the high crime of treason against the republic, and thus properly made his rendezvous with the hangman’s justice.

But it is within the realm of probability that a future Kenya government will revisit this episode of our history. Such a government could conclude that Ochuka and his cohorts were not criminals but patriots attempting to free Kenya from dictatorship. And like terrorists who morphed into freedom fighters before or after their deaths, he would be rehabilitated and claim his place in the sun in our national story.

That may or may not happen. What, however, is certain is that in profoundly personal and public ways, Ochuka’s intervention in our political life on August 1, 1982 changed our lives.

As his date with the gallows that were to be his destiny neared, the career of his nemeses on that wild Sunday morning, Gen Mahmoud Mohammed, started on its meteoric rise.

Senior officer

Mohammed was serving out his days of terminal leave and so was the only senior officer left behind when the rest of the armed forces were away in northern Kenya simulating a Sudanese attack on Kenya over oilfields in Turkana and the country’s would-be response. This is how it fell upon him, at the head of just a skeletal force, to beat back Ochuka’s euphoric conspirators.

President Moi put the brakes on Mohammed’s retirement and made him the Air Force Commander and later Chief of Defence Forces. He would go on to become one of the richest men to ever don a Kenya Defence Forces uniform. Meanwhile, the lives of thousands of soldiers and their families were turned upside down and many never recovered.

Long prison sentences, many completely unjustified, followed. Arbitrary sackings and demotions became the order of the day and formerly stable families broke up under the stress of the convulsions engulfing the Air Force fraternity. The year 1982 destroyed an uncountable number of Kenyans without actually taking their lives, a fate sometimes worse than death.

Nairobi, the capital where all this took place, changed its character completely. Following the widespread violence and looting that took place during the coup attempt, dazed traders vowed never to suffer such losses again.

A paradise

Until then, the city had been a window shoppers’ paradise. During long and safe hours of the night, people, especially lovers, would walk the streets taking in the delights displayed behind glass windows.

In an excellent article titled ‘The City of Gates’, architect Alfred Omenya bemoaned the loss of Nairobi’s glazed shopping windows thus: “They were replaced by gray, ugly, metallic roller shutters; afterthoughts that denied the eyes the opportunity to enjoy the visual pleasure of the ‘unreachables’ contained inside the shops. The poor citizen is thus denied what architects like to call the ‘capacity to aspire’”.

It is 1982 that converted Nairobi into the big, ugly slum that for the most part it is. Of course, it exported this trait of being severely challenged in the area of aesthetics to the rest of the country, as it does with everything else. Security, to the exclusion of almost everything else, became an obsession and the sight of poor people was now the strong warning sign that danger was at hand.

Again, Omenya captures it well: “Nairobi is not a planned city. It is a city built on reaction, on an incremental fervour, on the need to exclude and protect, to smother our neurosis – realistic to some extent – that the barbarians will get us. It is the insecure classes, feeling themselves to be unsecure, whose fears shape the city”.

To the citizens of Nairobi, the notion that security began with themselves seriously took root in the aftermath of August 1, 1982. And the metal industry boomed.

Yet it was the area of governance that the profoundest effects of Ochuka’s putsch were felt. Between 1960 and 1982, an African country that had not had a military intervention in its political affairs, either successfully or otherwise, was the exception rather than the rule.

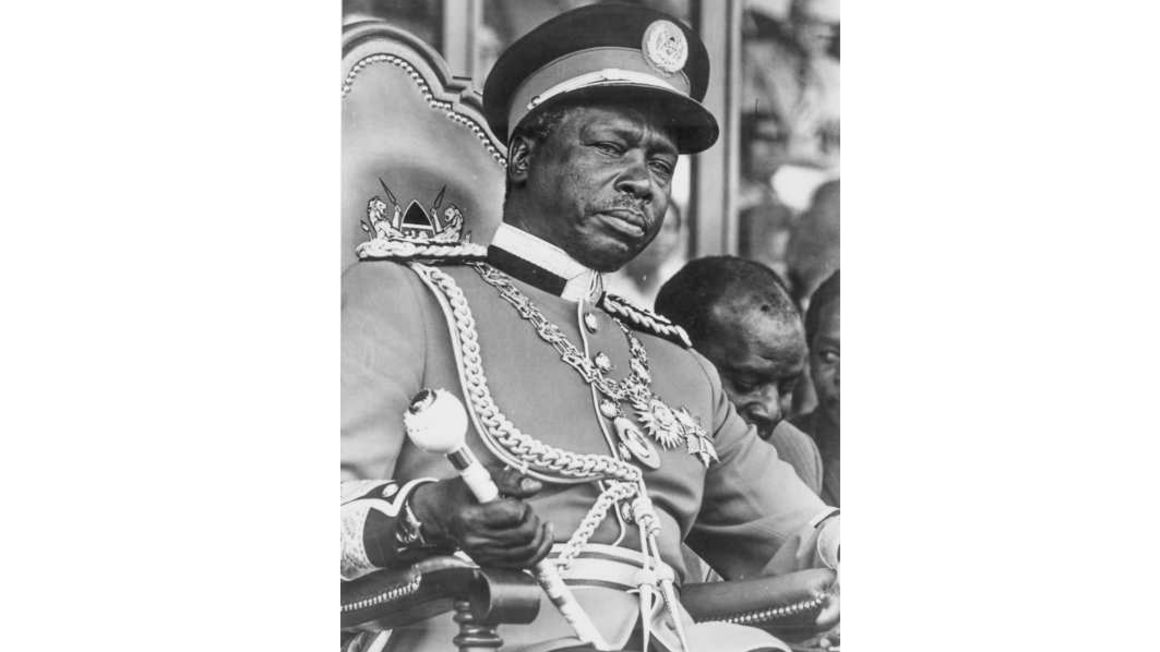

Among Kenya’s neighbours, only Tanzania to the south was peacefully ruled by a civilian administration. The rest – Somalia, Ethiopia, Sudan, Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi – were under military strongmen. The situation was much the same further afield.

By crushing Ochuka’s coup attempt, the Kenya Army almost certainly saved the country the familiar African story of coups and counter-coups and set the country on course to change its governments only through elections. And for its part, the military established for itself a reputation of being professional, meaning being apolitical and subservient to civilian authority. Kenya thus placed itself in the column of democratic countries, but the jury is out about how well it has fared.

In his study of the world’s democracies, Mancur Olson coined the term “distributive coalitions”. In his seminal book, Rise and Decline of Nations, Olson describes distributive coalitions as interest groups that continuously accumulate more and more power and soon become powerful enough to capture political institutions. When that is accomplished, they work for themselves and not the public good. At that point, the country gets into a state of political decay, and it gets worse by the day.

He also says there is no solution to this problem; no democracy can fix this problem once distributive coalitions capture the system. It is solved in one of only two ways: a revolution or an external shock, such as a war. Short of that, there is no way to break out of it.

In September 2019, many people were aghast when the former Israeli Ambassador to Kenya, Noah Gendler, publicly announced that he had requested to be recalled home after only two years on the job because he saw no use in serving in a country where the government was hostage to faceless powers who operated outside the established government system.

He said: “In the history of Israel, no government-to-government development project has ever failed. I am talking about the Galana-Kulalu irrigation project. It is the first ever to fail in the history of Israel”.

Political decay

Have powerful interest groups – to use the correct Kenyan term, have cartels – captured the Kenyan state? If so, can the country correctly be described as being in a state of political decay?

Another problem Kenya faces is that the institutions that should act as the bulwarks of public good are the very ones that are millstones around its neck. Civil society, for example, should be a driver of public accountability. It has been held up as the panacea for our problems, a counterweight to corrupt government. But civil society is the most fertile ground for the breeding of distributive coalitions – or cartels.

As a matter of fact, civil society that is committed to keeping the government in check, is totally motivated by public good, and is ethical and transparent in its dealings, has become something of a rarity in the country.

Finally, all political problems in Kenya have become judicial ones. Nothing can get done without going through an indeterminate process of public participation, legislation, lawsuits and counter lawsuits. Even to build just a small market or a footbridge over a stream can take years to accomplish. And all this time, cartels are… yes, you said it, eating.

How are taxes serving the people of Kenya today? And how were they serving them when the first General Election after independence was held in 1969? What would a graph of service delivery to the public between these two periods look like?

German ruler

When Erick Honnecker, the last East German communist ruler, died, a perceptive West German commentator remarked of the slightly built dictator: “Erick Honnecker was himself just a small man but his misdeeds are going to keep us busy trying to undo for generations to come”.

Hezekiah Ochuka was a poorly educated, low-ranking non-commissioned officer of the Kenya Air Force who, with better luck, might have pulled off a Samuel Doe, an Idi Amin, a Jean-Bedel Bokassa or a Mobutu Sese Seko. A Captain Thomas Sankara? Not by the clues he dropped.

But he changed Kenya, even if way differently from the script he had written. His failure kept the Kenyan soldier in the barracks and made the lawyer king in our public affairs. Now you’ll hear people who never went to law school quoting sub-sections of the law to make mundane points in social settings. It can get very heavy going.

God will help us.

When he realised that his ill-conceived and even more incompetently executed plan to take over the government of Kenya had become a hopeless failure, Ochuka activated Plan B — escape. He tricked his fellow conspirators into believing that he was going to Laikipia Air Base in Nanyuki to fetch reinforcements. To this, his men readily agreed.

He would go there with his trusted number two, Pancras Oteyo Okumu. Then he put a gun to the head of a pilot, an officer of the rank of Major named Nick ole Leshan, who flew Buffalo transport planes. Leshan was in the company of another officer, Major William Marende, a fighter pilot. Marende had never flown Buffalos and was only a very competent passenger, but most important a cherished companion in distressed times.

Took off

With Leshan at the controls, captors and captives took off. But as soon as they were airborne, Ochuka ordered Leshan, a future Air Force Commander, to change course for Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Dar was a safe destination, he thought, because it was Kenya’s enemy at the time. Looking at the levels of his tanks, a horrified Leshan told the gunman that they didn’t have enough fuel to reach Dar. But a very mellow Ochuka told him: “Afande, Mungu atatusaidia (“Sir, God will help us.”)”.

The irony of a hijacker addressing his captive as “Sir” didn’t escape Leshan. But he was too busy to say anything else. God, nonetheless, helped as Ochuka had prayed, because they got to Dar.

A completely exhausted Leshan would later say he briefly passed out as soon as he landed the aircraft and brought its wheels to a complete stop. Kenya and Tanzania closed ranks and the two hijackers were repatriated to the country to face justice. But the effects of what they did is still keeping us busy and will continue to do so for generations to come.

gachuhiroy@gmail.com

Credit: Source link