Early last month, Manchester City boss Pep Guardiola just came out and said it: “I love to overthink and create stupid tactics.” But for a manager who often seems to be pushing himself to the precipice of madness by layering in new levels of complexity to a completely made-up game, his most recent major solution was simple. Even he admitted it.

After losing to Tottenham on Nov. 21, 2020, City were 13th in the Premier League. A season after coughing up the league to Liverpool, they looked hopeless without the ball and frustrated with it. But come early January of last year, they hadn’t lost another game. They were on the verge of reeling in Liverpool and ultimately blowing past them and the rest of the league. What changed?

“The only difference is that we run less: we were running too much,” Guardiola said. “Without the ball you have to run. But with the football you have to walk, or run much less: stay more in position and let the ball run, not you. That’s improved in these games.”

By slowing things down, City easily won the league last season and now only need a win against Aston Villa this Sunday to do it all again. They won the race, and they’re winning the race — by pumping the brakes. Then why spend €60 million to sign Borussia Dortmund‘s Erling Haaland, a striker who doesn’t know slow?

If they want to keep winning the league and finally nab that elusive Champions League trophy, maybe it’s time for Manchester City to pick up the pace.

Why Haaland doesn’t fit Manchester City

Since the start of 2020, only one player has more non-penalty goals in domestic play across Europe’s ‘Big Five’ leagues than Haaland: Bayern Munich‘s Robert Lewandowski. Here’s the top five:

- 1. Robert Lewandowski: 75

- 2. Erling Haaland: 54

- 3. Cristiano Ronaldo: 50

- 4. Kylian Mbappe: 49

- 5. Karim Benzema: 48

Two things separate Haaland from those other four, though: 1) He’s 21, two years younger than Mbappe, and 2) He did it in 5,386 minutes, while no one else in the top five (or top 10) played fewer than 6,000. On a per-90 basis, Haaland has scored 0.90 non-penalty goals, much closer to Lewandowski’s rate of 1.01. Among players with at least 4,000 minutes of game time since January 2020, no one else is above 0.73.

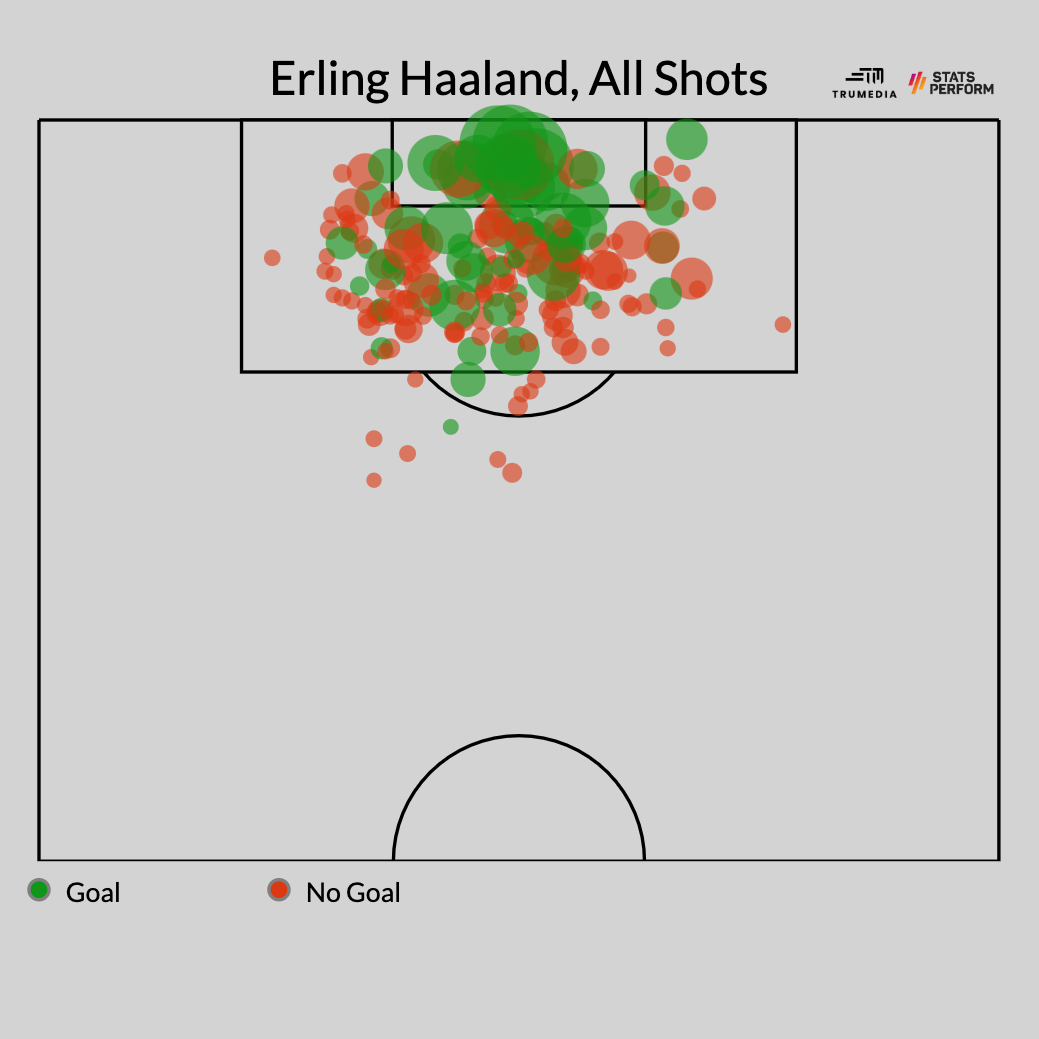

Now, Haaland has been running hot — likely to an unsustainable degree. He’s scored nearly a goal per 90 on an expected-goal-per-90 rate of 0.72. He’ll likely regress toward that number soon, but even still, that number is also only bested by Lewandowski. His shot map is the high art of soccer’s fledgling analytics movement: just 12 attempts from outside the box in two-and-a-half seasons and a morass of makes from the penalty spot, all the way up to the goal line.

It’s mostly goals you’re getting from Haaland, but not just goals. Among center-forwards with at least 4,000 minutes played since the start of 2020, Haaland ranks 13th in assists per 90 (0.25), 24th in expected assists (0.16) and 10th in touches in the penalty area (6.65). He’s not knitting together possession play or dropping deep to create — among those same strikers, he ranks 106th out of 120 players in touches per 90 — but his sheer physicality, referring to his size (6-foot-4) and his speed (22 miles per hour!), opens up space for him in the penalty area and creates relatively simple passing lanes to create chances for his teammates.

Of course, a striker who doesn’t touch the ball doesn’t seem to fit with a team that’s always touching the ball. Neither does Haaland’s reliance on transitional opportunities. Since 2020, he’s been involved in 14 goals (eight goals, four assists) from counter-attacking situations — more than any other center-forward.

Just look at all of his Bundesliga goals. Very few of them come from the situations from which Manchester City create the majority of their goals: settled possession, recycled from side to side. No, it’s all power-runs into the space in the center of the box.

This past season, City’s uninterrupted possessions (sequences) that lead to shots have moved the ball up the field 1.47 at meters per second — slowest in Europe. Those possessions have an average of 4.19 passes — most in Europe. And they last for 13.14 seconds — longest in Europe. At Dortmund, they move faster (2.23 m/s, 55th percentile), pass less (2.89, 70th percentile) and don’t hold the ball for as long (8.74 seconds, 66th percentile) when they create shots. Across those three numbers, Dortmund’s profile is almost identical to … Aston Villa’s.

So can Haaland adapt? Or should Manchester City start playing more like a mid-table team?

Why Manchester City should change to fit Haaland

It seems absurd to suggest that the greatest young goal-scorer on the planet — a player who’s already among the best in the world and is still years away from his prime — might not make a team better. But, well, it’s hard to imagine a team that’s any better than Manchester City is right now.

Per Stats Perform, City’s per-game xG differential is currently plus-1.87. Since 2010, the only team in the Big Five leagues with a better mark was Paris Saint-Germain in 2019-10 (plus-1.93), and the only team to match City was Barcelona in 2015-16. Given that the overall competitiveness of the Premier League is maybe higher right now than it’s been in any league over that stretch, I’m not sure it’s possible for City to notably improve on the things they can control: suppressing and creating chances.

That being said, I think the Haaland signing suggests something slightly different: that City want to be different. Not only should it be impossible for City to improve; it should be next-to-impossible for them to maintain their current level. But if Haaland hits, then maybe they can keep going, albeit in an entirely new and different way.

You can break Guardiola’s time at City into two distinct eras: The Fernandinho Era and the Kyle Walker Era.

Guardiola’s first two title-winning seasons were built around the Brazilian holding midfielder more so than any other player. They played a high-flying, high-pressing style that introduced the idea of “free No. 8s” — players who previously would have been “attacking midfielders” in front of a pair of holding midfielders were now playing as a pair of attacking midfielders in front of one holding midfielder. City were able to do it because they had Fernandinho, a player unlike anyone else in the world. He snuffed out counter-attacks all by himself — often through tactical fouls — but he also contributed to possession play with line-breaking progressive passes.

With Fernandinho at the base of midfield, they put together perhaps the best two-year stretch in the history of domestic football — 100 points, then 98 points — but the cracks started to show in 2019-20. Fernandinho still played most of the minutes, but he was 34 and had lost a lot of his physical range. They finished second, scoring 102 goals but allowing 35, 12 more than the year before. Then it all fell apart in the first few months of last season. Fernandinho was phased out for Rodri, but his real replacement was another one-of-a-kind player in Kyle Walker.

With Walker, City were able to transform into playing such a deliberate style because everyone on the field was comfortable and dangerous in settled possession. Rodri, Joao Cancelo and both center-backs were all very involved in passing play in the final-third. This let them keep possession for longer without having to press (and run) and it also added extra bodies for the defense to pay attention to.

The problem: all that space behind. The solution: Walker’s recovery speed.

The England international was capable of overlapping his same-side winger, but was also proficient enough with the ball at his feet that he could help recycle and probe possession alongside the center-backs. Whenever the opposition broke free with a ball over the top, Walker would chase down the winger or the striker and slow the other team down. There isn’t another player in the world who has the 1-on-1 defending ability, the passing and the blazing open-field speed that he does.

Right now, there’s no one else who can do what Walker does for City. They’re simply a different team without him:

Number of opponent's fast break attacks reached #ManchesterCity third (per 90):

with Kyle Walker – 0.8

without Kyle Walker – 1.5* 'fast break' – first 10 seconds of possession after turnover

** this type of analysis might be impacted by strength of opponent pic.twitter.com/46IYwYlGrZ— markstats (@markrstats) May 15, 2022

It’s a bit of an oversimplification, but it illustrates the same point: City allowed zero goals against Real Madrid with Walker on the field, and six with him off of it. The issue with employing Walker as your skeleton key is that he turns 32 in two weeks, and he’s playing one of the more physically demanding roles in the sport. He hasn’t broken 2,000 minutes in either of the last two Premier League seasons, and it would be silly to rely on him doing it ever again. The team is going to decline if they do.

So rather than trying to replace the irreplaceable Walker, and fit Haaland into a system and style of play that’s incredibly different from anything he’s played in before, maybe City will shift to an approach that plays to Haaland’s strengths and lessens the need for Walker.

What would that mean? Less control and more transition. More possessions changing hands. It would require City to be willing to concede more goals for the benefit of scoring more. It would mean faster forward passing, at the risk of losing the ball more often, for the reward of capitalizing on all the space that Haaland is better than anyone else in the world at running into.

It might also mean more success in Europe. While City’s slow-mo style clearly fits the 38-game slog of a Premier League season, it’s unclear if it’s the right way to play in the Champions League. Yes, they reached the final last season and were mere seconds away from making it back this year, but City haven’t been quite as dominant in Europe as their league form suggests they should be. One of the reasons is likely that they simply can’t control the game against Europe’s top teams in the same way as they do in the Premier League.

Beyond that, a decisive goal-scorer is simply way more valuable in the volatility of a knockout competition than across a 38-game season when things tend to even out. No City player has scored more than 15 non-penalty goals in each of the past two seasons. Since Guardiola came to the club, City haven’t “stolen” a single result in any Champions League match; they haven’t had an individual player take over and render the previous pattern of the game meaningless. No, that always happens to them.

Ultimately, City didn’t sign Haaland so they could keep dominating the Premier League. They signed him so they could finally win the Champions League. But if they really want to do that — and if they want to do it with Haaland leading the way — then it might be time to forget about the ball and start running again.

Credit: Source link