A man in his prime is arrested, tried and sentenced to hang. For years, he is in jail among a group labelled “condemned” till 2016 when presidential pardon gets him out.

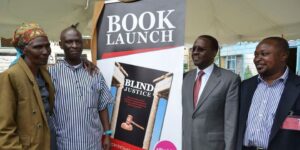

Three years before the pardon, Haron Thomas Nyandoro released a book, Blind Justice, written behind prison walls. The launch of the book was attended by then Chief Justice Willy Mutunga, and the then Director of Public Prosecutions Keriako Tobiko.

And now, six years after his release, his book is being adapted into a full-length film by Freenation Films.

In the book, Nyandoro claims he did not commit the robbery with violence that put him on death row.

The story begins in 1997. One day, Nyandoro is taken to Nyangusu Police Station and accused of being in a group of seven that allegedly robbed a woman of Sh75,670.

That arrest takes an interesting twist when the narrative of a rich and influential magistrate comes into focus. The magistrate wants to buy a piece of land from Nyandoro’s father but Nyandoro stops the transaction as he believes the land should remain the family’s property.

This action triggers enmity. Unbeknown to Nyandoro, the magistrate lays numerous traps to capture and kill him, believing that if Nyandoro is out of the way, his father will easily part with the land. All the traps fail. Except one.

Nyandoro is finally captured but before his life is snuffed out, a crowd coming from a funeral vigil saves him from death and he is handed over to the police.

“The rest is a moving story about a failed criminal justice system, a cruel prison system, the heroic suffering and stoic faith of a mother and the unyielding quest for justice by an innocent man,” reads the book’s blurb.

Nyandoro starts the book by giving the background of his life and family. As the story unfolds, there are numerous attempts on his life until he is tricked into being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Then he is captured by an unknown group of people.

As he is handed over to the police, Nyandoro protests and tries to assert his innocence regarding the charges against him. Initially, he is confident that the truth will set him free.

As the book progresses, his numerous attempts to clear his name and gain his deserved freedom fall like dominoes. The end result? A mandatory death sentence – though he was technically on a life sentence because Kenya has not hanged a convict since the 1980s.

Nyandoro demonstrates the full range of human emotions through his different challenges from those opposed to his release. His family remains sympathetic to his plight and try their best to support and maintain his sense of hope and faith.

Despite facing courtroom injustice, starvation, violence and abuse, Nyandoro shows how, even in the darkest of days and situations, humans can still band together and support each other in the simplest of ways. The book has a surprising ending that leaves the reader yearning for a sequel.

Being a true story, there is a forewarning in the introductory pages of the book: “Some of the events you will come across in the story may be scary, extremely inhuman or even seem exaggerated. However, not a single one of them is next to fiction.”

Given the suspense-filled ending to the novel, the feelings of hopelessness and sadness that the author is trying to convey are relayed in a unique way.

Speaking with Lifestyle, Nyandoro said it took him years to write the book.

“I had written more than a dozen manuscripts; all of them on tissue paper. Back then, we were not allowed to even have a pen, let alone a book, in our cells. But that changed when then Vice President Moody Awori, or Uncle Moody (under President Mwai Kibaki’s administration), as he was popularly known, came and decided to change everything. He turned prisons into proper correctional facilities with humane consideration rather than places of torture and punishment,” said Nyandoro.

He said he befriended a prison guard who gave him a pencil and that is how he started writing. But every other month, prison guards would come and search their cells and if any contraband was found, it was thrown away and the owner punished.

“I never gave up,” said Nyandoro. “I kept on starting all over again and again until the radical prison changes by Uncle Moody came into effect.”

After the changes, Nyandoro said he sat down to write his book. At the same time, inmates were not allowed to write about things against the prison system.

“There was a school in prison and I was elected to be teaching other prisoners. I took that opportunity to write without anyone suspecting that I was writing a book,” said Nyandoro.

His woes did not end there, however. The next step after finishing his book was how to get it out there to have it published. He noted that once the book was published, it caught the prisons authorities by surprise.

“One prison guard said it was as if I had already broken out of prison; that I was inside and outside at the same time. I was happy because people could read my book. Then Chief Justice Willy Mutunga read it and came during the launch of the book while I was still incarcerated,” said Nyandoro.

He believes that were it not for the book, he would still be inside: “The book really helped in my release. After the launch of the book, I became a unique person in prison. I started receiving many visitors and it reached a point where the prison warders said enough was enough and they didn’t want me anymore.”

Before his release, Nyandoro was put in isolation; at a section previously holding political detainees during the dark days of the Nyayo era.

“They put me there and said I could be given special treatment. But I refused, fearing that staying alone there could have made it easier for them to kill me. I insisted on being held in the general cell with other prisoners,” he said.

As a Catholic, he describes 2016 – the year he was released – as the year of mercy. He said he had prayed to God to set him free.

“In 19-and-a-half years and after all the prayers, nothing had happened. I told myself that I was probably not praying enough. So, I stopped praying and told God to have mercy on me. In the year I was released, I only told God to have mercy on me and that was the year of mercy. I think my basket of mercy was full,” said Nyandoro.

Nyandoro grew up a follower of the Catholic Church and was mentored by the late Fr John Anthony Kaiser.

“I believe in truth. So, it has never been easy for me to accept that I was on death row for a crime I did not commit. But more painful is the fact that the custodians of justice from the bottom to the Court of Appeal could not see the naked truth in this case; hence the title of my book, Blind Justice.”

When Dr Mutunga and Mr Tobiko visited the Kamiti Maximum Security Prison in 2013 for the Judicial Service Week, the launch of his book was also part of the programme. While launching the book, Dr Mutunga commended prison authorities for the reforms that had taken place in correctional institutions to the point of inmates being allowed to write books.

Nyandoro’s story is bound to get a larger audience after an international producer pledged to make a film out of it. He said he had been approached by several film directors who wanted to turn his book into a film.

“Since my release in 2016, I have talked to so many people who wanted to take my story and make a film but I refused after I looked at their profiles,” he said.

According to Nyandoro, he settled for Neil Schell – who has acted with Liam Neeson in the blockbuster movie “The A-Team”. Locally, he has directed “Monica”, starring Brenda Wairimu, and has also coached Nick Mutuma.

“I cannot wait to see who will play me. Schell is writing the script and will also direct it. We hope to start shooting before the end of the year,” said Nyandoro.

The film is now in the casting stage. Nyandoro looks forward to seeing who will be cast and what its end will be like. Even in film, the story will be about Kenya and the injustices of its criminal justice system.

Nyandoro said he is writing more books, which will be published after the release of the film. He said he is also working on the conclusion of Blind Justice because it left many wondering what happened next.

“Society needs to understand that some of the people they see languishing behind bars are innocent. I hope the Judiciary can right some of these injustices,” he said.

Nyandoro, who believes that everything happens for a reason, added: “God is the ultimate judge. Every single magistrate and judge, except one, all who refused to see the naked truth in my case, have been removed from the Judiciary for one reason or the other, some over allegations of corruption and incompetence.”

His pain was exacerbated by the fact that his appeals were unanimously dismissed despite an unambiguous concession by one State Counsel at appeal that the trial court’s judgment was not supported by the evidence adduced.

It was alleged he was armed with a gun when he was arrested. The gun was never produced in court as an exhibit and there was no explanation on how it disappeared from the scene of crime as his accomplices had by then allegedly escaped.

“If I had a gun and was arrested at the scene, where was the gun? Notably, the investigating officer never testified in court either in writing or in person,” he said.

Nyandoro’s case was subsequently consolidated with another involving one John Ondabu, who died in harsh prison conditions. Nyandoro maintains he never knew the late Ondabu until he learnt about the consolidation of their cases.

Life in incarceration meant that family life disintegrated. Even though his mother was a constant visitor and pillar of support, there was a gaping hole in his personal family life.

His wife left him and even got married three years after he started his prison term. She left with their two daughters, now aged 27 and 25.

“She moved on with them. But I tried to get the girls in my life and eventually they came around to visit me in the 17th year of prison onwards. They saw their father and they knew instinctively that I was innocent,” said Nyandoro.

He added that they are now fully in his life and in constant touch.

“We are making up for lost years and I treasure every moment with them,” he said.

After leaving prison, he has been reinventing himself. Part of this involved remarrying, and he is now a father of two boys.

“I named one Kaiser Nyandoro after Fr Kaiser of the Mill Hill Fathers, who was a mentor in my fight against injustice,” he said.

Fr Kaiser was a priest from the US state of Minnesota who was assassinated near his mission at Morendat, Nakuru County.

Nyandoro said he cherishes Fr Kaiser’s ideals as they kept him alive in prison.

“Family life provides one with purpose and motivation to work for the wellbeing of the next generation. It is a gift of God to man,” said Nyandoro.

“I survive on prayer and commitment to my businesses. I enjoy moving around without people knowing who I am. I like writing, a habit I adopted while behind bars,” he added.

Credit: Source link