In the 1960s and 70s, it was common knowledge that most sportsmen and women had a day job to supplement the little money if any, they made from sports. So, who used to take all the money in sports?

Team owners were rich and powerful. A player could only leave a club with the express permission of the owner because sports labour laws were pro owners.

In Kenya, most sports teams were either controlled by parastatals or government ministries. Therefore, meeting your gold medal winner at the local Post Office selling stamps or as a cashier at your local bank was a common sight.

Unknown to many at that time, there were many grumbles and bargaining going on in Labour courts and boardrooms on the need to improve players’ welfare.

Finally, between 1975 and 1995, various sports federations and owners ceded more and more power to the athletes and voila! A new era of sports dollar-millionaires was ushered.

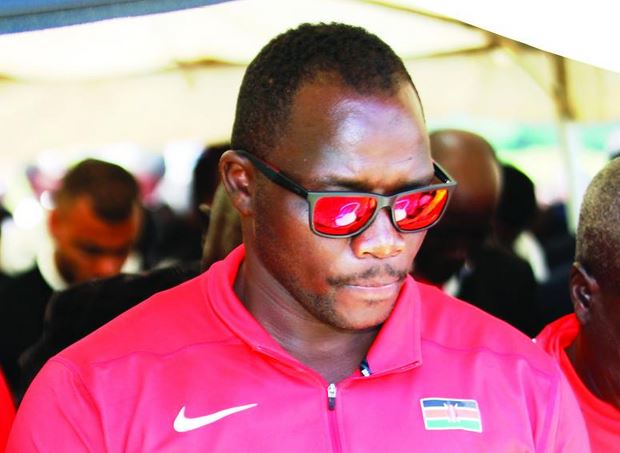

For a while now, as Kenya’s sports legends have unfortunately been passing away, their funerals look and feel the same. Every speaker talks about how we have neglected our heroes and left them to die in abject poverty.

The case was no different recently at the funeral of the legendry Ben Jipcho. Wealthy political leaders and law makers complained of how the government had abandoned the athlete when he needed them most.

Even in death, we still salute these greats since they laid the foundation for the lucrative sports industry many athletes are living from.

However, in spite of the improved player terms, many contracted athletes still retire into a life of ridicule and poverty after many years of earning millions of dollars on the racetrack. Kenya and the world are awash with athletes who rose from rags to riches and back to rags.

What is the problem? Is it the contracts? Is the money coming come too fast, and too soon for athletes? Why don’t some athletes see the brevity of their careers and start to save from their first pay cheque?

To appreciate a typical elite athlete’s annual earnings, let us deconstruct a typical runner’s contract.

Most elite runners have an apparel company contract from brands such as Nike, Adidas, Asics, Under Amour, Mizuno, Puma, and many more. The contract is divided into the following compensation clauses: base compensation, performance bonuses and products for athlete’s use.

The base compensation is basically a lump sum amount paid semi-annually and if well negotiated can go into millions per year.

Performance bonuses are paid for medals won, good global rankings or records broken and are at a pre-determined rate.

Branded apparel from the sponsoring company are delivered to the athlete both at pre-season and on-season.

The first tricky part of sports contracts is that for the base compensation and performance bonuses to be paid; the athletes and their management must send an invoice to the sponsor.

Should the invoice not be submitted, they will be deemed to have forfeited their right to be paid.

To most athletes, the arrival of the base compensation money either ushers the start of a long line of payments or the beginning of the first and last sports contract.

At times, a huge sum could overwhelm and confuse the athlete.

Therefore, a good manager with the athlete’s interest at heart is needed to help the athlete stabilise fast and progress in their career.

As opposed to Gold labeled elite athletes (world champions and record holders) who often get individual contracts, majority of Kenyan athletes are on group (team) contracts.

These contracts have similar benefits to individual contracts, with the team manager deciding how much each athlete gets.

Most team athletes train in sponsored camps and receive all-rounded training and logistics support.

To make more money, they must compete and win in multiple events to get both appearance fees and performance bonuses.

Although the training and logistics support is good, the athlete’s welfare is always at stake in the event of injury or poor performance in competitions.

Athletes in both group and individual apparel contracts should, therefore, focus their sights on other product endorsement opportunities.

They could borrow from Eliud Kipchoge and Isuzu; Julius Yego and Orange/Telkom; David Rudisha and Kiwi/Blue Band to broaden their financial prospects.

Over the years, contracted athletes have always performed better than freelancers. This has attracted the attention of World Athletics who last month rolled out the Shoe Availability Scheme aimed at leveling the competition field as far as shoe technology goes.

The scheme will ensure that approved shoes are made available prior to an international competition for distribution to any un-contracted elite athlete.

This has provided a glimmer of hope for many athletes who without access to the exclusive and cutting-edge shoes would never dream of a podium finish.

Could this scheme be a game-changer and usher in another era where elite athletes can get the services of top-end running shoes but without the responsibilities of an apparel company’s contract? Only time will tell.

Elite athletes live and work in the fast and flashy lane over a short period of time which is usually their formative years too. The intense globe-trotting schedule of an elite athlete prevents them from doing anything else such as going to college.

The lack of essential life skills exposes them to many vices and errors of judgement leading to a reckless spendthrift life that eventually returns them to the very poverty they were literally running away from.

Take for instance a win at a one day Diamond league meet. An athlete will pocket US$ 10,000 (Sh1 million) before adding time bonuses and event sponsors endorsements.

By the end of the year, the teenager has money beyond his comprehension and in need of good investment guidance.

An honest manager should not only give the athlete his dues accompanied with a clear and simple-to-understand breakdown of expenses but also advise the young one on how best to invest the money.

This is what some teams such as NN Running that manages the likes of Eliud Kipchoge, Kenenisa Bekele, Joshua Cheptegei and Sally Chepyego among a host of other global stars are doing.

It has taken athletes many decades to reach this far in contract compensation.

It will be a shame if the current generation waste the opportunity to make a decent living from athletics and convert sports success to a curse.

Paul Ochieng is a Sports Economist and Dean of Students at Strathmore University.

Gerald Lwande is a Biomedical Scientist

Credit: Source link