Before the season, everyone was picking Everton to get relegated. After finishing with 39 points — a massive drop from the season before — the trajectory looked like it might be irreversible. They’d won seven league titles, they’d been in the first division since 1954, and the Premier League hadn’t existed without them. But English soccer’s post-Everton era was just 38 games away.

Then … they finished fourth — at least that’s what happened the first time around. After finishing in 17th in 2004, with the fewest points in club history, during David Moyes’s first full season at the club, Everton were a popular pick for relegation and Moyes looked like a good bet for First Manager Sacked. Instead, they qualified for the Champions League and then, over the next eight years, established themselves as one of the best-run clubs in Europe: consistently outperforming their budget, unearthing unexpected stars, and frequently finishing just outside the top four. The operation was so impressive that Moyes was seen as a no-brainer replacement for the most successful manager in Premier League history, Sir Alex Ferguson.

This time around, well, you might as well flip that previous paragraph inside out. With 18 games to go, Everton are in 19th, tied with Southampton for the fewest points in the league. Per FiveThirtyEight, they’re the heaviest favorites for relegation: with a 68% chance of going down. The bookies have them as second favorites after Bournemouth. They just fired their manager, and they’re certainly in the running for Worst Run Club in Europe.

How’d it happen? Here’s Everton’s step-by-step guide to getting relegated.

1. Don’t have a plan

This is the major inefficiency across European soccer — especially in England. Spending in the transfer market still has very little correlation with team success, which suggests that no one is all that good at understanding what wins soccer games. And when you have access to the riches of the Premier League broadcasting deal, you theoretically have the capacity to sign, I don’t know, 95% of the sport’s global playing population.

One way to sift through the unlimited possibilities — and likely failures — of player acquisition is to create a context for those players to fit within. Almost every successful club in Europe has committed to some kind of identity and then built toward it.

By committing to a general approach to the game, you accomplish a number of different things. You filter out thousands of players who don’t fit that approach. You make the players you’re attempting to sign more likely to succeed by reducing the chance that they don’t fit with the manager. And you make your roster immune to the cycle of death that is the manager-squad mismatch: where players are signed to play a certain way under a certain coach, that coach is fired, a new coach is hired, and half of the players you just signed don’t fit the new coach, so he gets to sign new players but then gets fired because he’s still coaching a bunch of players he doesn’t want, and on and on until you become Everton.

2. Keep riding the managerial merry-go-round …

Under Moyes, Everton were one of the most clearly defined teams in Premier League history. They always had one fullback who attacked and one who didn’t get forward much. They had one midfielder who wouldn’t lose the ball, and another one who would muck things up. They had a traditional hold-up striker and then a large, hybrid midfielder-attacker who would break into the box. And on the wings, there was a collection of tricky not-quite-wingers. This enabled them to counter against the big teams, keep possession against the smaller teams and defend well against everyone.

Moyes left the club right as the “manager” model was going out of style; the manager, very quickly, was being merged into a larger decision-making hierarchy, rather than controlling everything himself. Replicating the Moyes Era was always going to be impossible because of the structural changes happening across the sport. From 2009 through 2013, his Everton teams averaged 1.6 points per game, 1.4 goals scored, and 1.1 conceded.

Everton first replaced Moyes with Roberto Martinez, who had just been relegated with Wigan, but had also just won the FA Cup with Wigan. Although it eventually led to demotion, Martinez had Wigan playing an ambitious, attacking style that the Everton brass assumed would only scale up with the talent and resources of a bigger club. In Year One, they were right; the club finished in fifth with 72 points — more than in any Moyes season. But then they finished 11th in each of the next two seasons and Martinez was sacked. They scored more goals under Martinez (1.5), but the defense got worse (1.3 goals conceded), and so did the team (1.4 points).

In the summer of 2016, Ronald Koeman replaced Martinez. Koeman was an “attacking” manager, in theory, but one who prioritized a much more defensive kind of possession. He’d also replaced Mauricio Pochettino at Southampton and taken over a team that already had a ton of talent. Koeman lasted one-and-change seasons at Goodison Park and essentially maintained the same level as Martinez: same goals scored and conceded, but slightly more (1.5) points. He was replaced mid-season by Sam Allardyce, the defend-and-win relegation savior, who didn’t fix the defense (1.3 goals conceded), made the attack worse (1.1 goals), and made the team worse (1.4 points), but still somehow avoided the bottom three.

Next up: Marco Silva, who was a pivot back to the Martinez model — a recently relegated manager who’d developed attacking soccer with a bottom-feeder team. He, too, lasted a year and a half — the goals increased on both ends (1.3 scored, 1.4 conceded) and the results got even worse (1.3 points). He was replaced mid-season by Carlo Ancelotti, an expensive big-name coach who didn’t improve the team (1.2 goals scored, 1.3 conceded) despite the improved results (1.5 points). Ancelotti then left for Real Madrid after the 2020-21 season.

The response to Ancelotti’s sudden departure? Rafa Benitez! He’s an incredibly successful manager, who … prioritized defensive organization over everything else and won the Champions League with Everton’s hated rivals, Liverpool. The results tanked (1.0 points per game), as did the defense (1.8 goals conceded, 1.3 scored). Benitez was fired midseason and replaced by Frank Lampard, whose only Premier League experience was with a young, resource-rich Chelsea team that allowed him to play a wide-open attacking style — essentially the polar opposite of the man he was replacing. Although they avoided relegation last season, the team was even worse under Lampard: 0.9 points per game, 0.9 goals, 1.6 goals allowed.

Last week, Lampard was replaced with perhaps the most defensive manager in Premier League history in Sean Dyche, who was reportedly one of the club’s top choices along with Marcelo Bielsa, who himself is the polar opposite of Sean Dyche.

As of last January, Everton had paid out £32 million in managerial compensation fees over the previous five years.

This is not the decision-making pattern of a club with a plan.

3. … and sign a ton of veterans

One of the biggest misconceptions in soccer is that young players are riskier acquisitions than established veterans. By definition, every veteran is somewhat near their decline. And by definition, veterans are going to command higher salaries, higher transfer fees, or both. So while it seems like you are theoretically paying more money for more certainty — you’ve seen more years of high performance from this player — that’s not actually true. You’re paying more money for less upside, and a much bigger downside.

Once a veteran player starts to decline, there’s very little you can do. Everyone else knows the player has started to decline, and he’s likely on a bigger salary, so you can’t go back to the transfer market. You’re also then stuck with someone who isn’t contributing to winning, but is taking up a sizable chunk of your team’s resources.

This isn’t to say that 28-year-olds shouldn’t be allowed to play professional soccer or anything like that. There are plenty of fantastic 30-year-olds out there — more so than ever before, in fact — but every move for a player in this age bracket is a risk. And when you stack up a bunch of players like this on your roster, you risk, well, becoming Everton.

In 2016, Farhad Moshiri became Everton’s major shareholder. Despite their wage bill significantly increasing over the stretch, their performance has actually declined. And since their performance has declined, their revenue hasn’t increased, which eventually put them at risk under the Premier League’s profitability and sustainability rules.

Unlike financial fair play, which only applies to clubs in European competition, the P&S rules essentially allow clubs to make no more than a £35 million loss per year. This, coupled with sanctions against Russia that have zapped away all the money coming from Moshiri’s “associate,” billionaire Alisher Usmanov, is why Everton haven’t been able to make many additions to the team over the past few years and also why the threat of relegation is suddenly particularly daunting. It’s also why the team is currently for sale; anyone want a club with disastrous finances and a 2-in-3 chance of being relegated?

So, how do you spend so much money on players and actively get worse?

In the 2016-17 season, Everton spent at least £10 million on three players 27 or older: defender Ashley Williams from Swansea City, defensive midfielder Morgan Schneiderlin from Manchester United, and winger Yannick Bolasie from Crystal Palace. The next season: £20 million on six players, three of whom were striker Cenk Tosun (26), winger Theo Walcott (28), and attacking midfielder Gylfi Sigurdsson (27). The next two seasons, under Silva, the approach seemed to change, as midfielders Fabian Delph and Djibril Sidibe were the only players signed over the age of 26. That immediately changed once Ancelotti arrived, though, and during his one full season at the club, midfielders Allan (29) and Abdoulaye Doucoure (27), playmaker James Rodriguez (29) and striker Joshua King (29) all joined.

That’s 12 veteran signings — almost none of whom moved the needle at all. Below that cohort, they also seemed to focus on adding mid-20s players from Champions League clubs: midfielders Davy Klaassen, Alex Iwobi and Andre Gomes, and defenders Lucas Digne and Yerry Mina. While “sign players from teams that are better than you” isn’t the worst scouting strategy, it certainly limits your upside because these players are expensive and there’s likely a cap on how good they can be — otherwise, they wouldn’t be available.

Combined with a strategy of scouring Europe for affordable young talent, you can see it as a cohesive team-building strategy for a team like Everton. But when paired with the “pay a lot of money for 28-year-olds” approach, it can end in disaster.

4. Panic

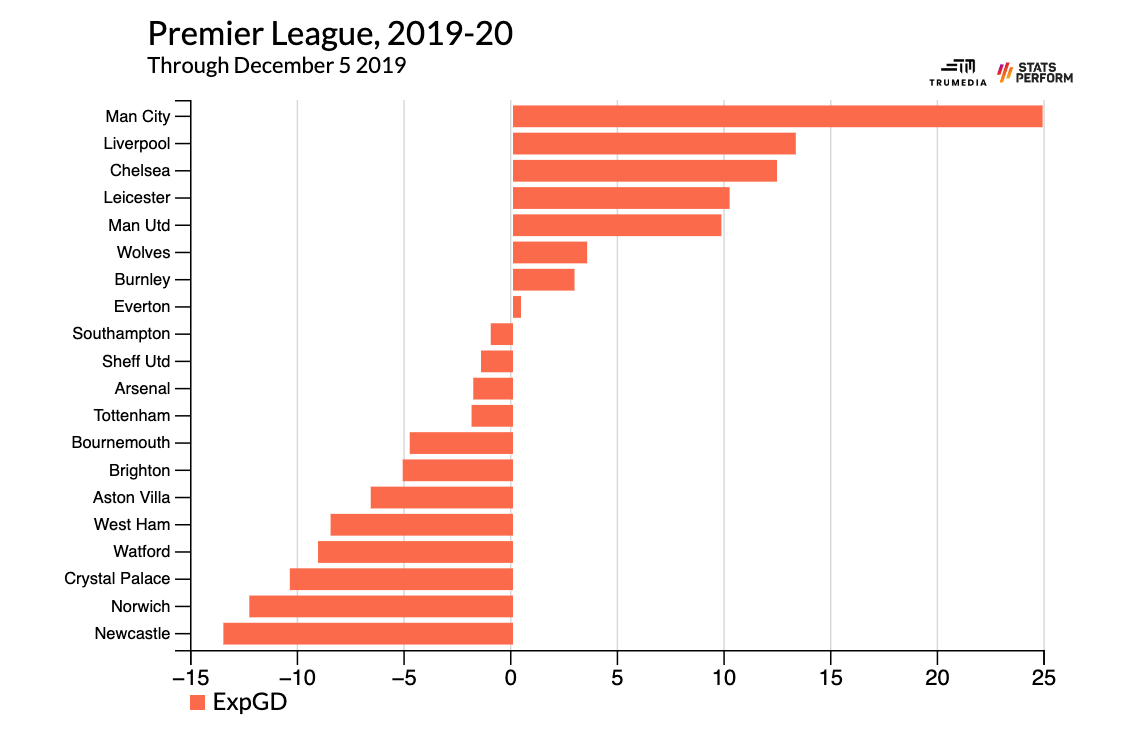

Among the seven post-Moyes managers, only one of them oversaw a team that produced a positive per-game expected-goal differential: Marco Silva.

In Silva’s first season, they finished in eighth with the second-youngest team in the league, weighted by minutes played. When Silva was fired in December of the next season, Everton were in 18th place — one point from safety. Except they were just as good at creating and suppressing chances as the season before; the finishing just wasn’t going their way. Their xG differential at the time of Silva’s firing was the eighth-best in the league:

After Silva left, Ancelotti came in … and the club bought a bunch of expensive veterans for a coach who would leave at the end of the next season. Perhaps there’s an alternate universe where Everton understand the volatility of finishing, they hang onto Silva, some bounces start going their way, they continue with a semi-patient team-building strategy, and they’re currently sitting somewhere in the top half of the table. Instead, they panicked.

Four years later, Silva is managing a Premier League team that’s currently in seventh place. It’s just not Everton.

5) Completely misunderstand who you are

Let’s say there are five tiers of Premier League teams.

At the top, you have the title challengers. Below them, you’ve got the top-four contenders (aka the rest of the Big Six). Underneath that: Europa/Conference League contenders. Then there are the teams with no real chance at Europe but no real risk of relegation, either. Finally, there’s the bottom tier: the relegation fighters.

Each tier has its own kind of financial cliff. If you get relegated, you lose your main source of revenue: the Premier League’s broadcast money, so establishing yourself above that tier is worth a ton of money. Then, matches in the Europa/Conference League are worth varying millions of dollars, so making the jump into that tier results in another sizable revenue boost. The leap into Champions League qualification, of course, is a massive boost. And then, well, winning the Premier League is the point of doing all this stuff in the first place.

If you’re realistic about where you stand, you can make smarter decisions. Teams at risk of relegation can make moves that raise their floor, but perhaps not their ceiling. From there, they can focus on stacking the marginal gains that allow you to establish yourself as a Premier League regular. Once you’ve done that, OK, what do we need to do to make it into Europe? How far away are we? And what kind of moves get us closer without risking a drop back into the bottom tier?

Given how much teams struggle to identify players in the transfer market, I think the default for almost every club should be transactions that optimize the team’s long-term potential. Even when a younger signing doesn’t work out — like, say, Henry Onyekuru, Nikola Vlasic or Ademola Lookman at Everton — these players still retain transfer value because of their age. Some seemingly long-term moves can also provide immediate dividends, and when you make a bunch of these moves and they all hit at the same time, you can make a sudden leap. Just ask Arsenal about how that can work.

But when you’re close to making it into another tier — close to qualifying for Europe for the first time, close to winning the league out of nowhere — then you can pull in the time horizon and make a couple of moves with a higher chance of an immediate payoff, but some more long-term risk. Even though I think every club over-values how safe any of these moves are — see: the lack of success in the January transfer window — there’s a time and place for them…

… and that time and place has almost never been the past decade at Goodison Park.

Among all those tiers, the least valuable — the least worth chasing — is the Europa/Conference League tier. Qualifying for the Europa or Conference League won’t change your life, and it’s also really hard to do on a consistent basis given the financial gap between the six biggest clubs and everyone else.

Yet for a decade, it seems like Everton have convinced themselves that they were on the verge of breaking into that group. Since Martinez’s first season, the team has never finished above seventh. They’ve qualified for the Europa League once, but they’ve been building the team as if they’ve been one player away from something for essentially a decade now. They’ve signed some 50-plus players over that stretch, and not only are they still not there, but they’re on the verge of being further away than they’ve ever been.

Credit: Source link