It’s easy to forget, but English soccer was not in a great place 10 years ago. Competitively, at least.

The Premier League was flourishing financially, with the fruits of the league’s early business savvy showing up in television deals that were beginning to dwarf any of Europe’s other major leagues. But despite a growing financial advantage, England just wasn’t producing teams that anyone could reasonably claim were the best in the world.

In both the 2007 and 2008 seasons, three of the four UEFA Champions League semifinalists were English. Liverpool won the whole thing in 2005 — in a season when they didn’t even finish top four in their own league. They made the final again in 2007, and then Manchester United and Chelsea played each other in the final in 2008. But after that, it just sort of stopped.

Over the next nine Champions League tournaments, the Premier League produced just three finalists: twice Manchester United were thoroughly dominated by Barcelona, and then Chelsea won it all in 2012, an occurrence that said almost nothing about the quality of English soccer and everything about the pure randomness often produced by 22 players attempting to kick a bouncy ball into a tiny goal.

Come 2016, the Premier League was the model for how to build a competitive, lucrative and constantly interesting league. But if you were looking for the sport’s bleeding edge — the best players, the most effective ideas, the highest level of execution — you had to go somewhere else in Europe. And that’s ultimately what the Premier League did, too. In 2016, the previous managers of Borussia Dortmund (Jurgen Klopp) and Bayern Munich (Pep Guardiola) competed in their first seasons in English soccer, and the rest is history.

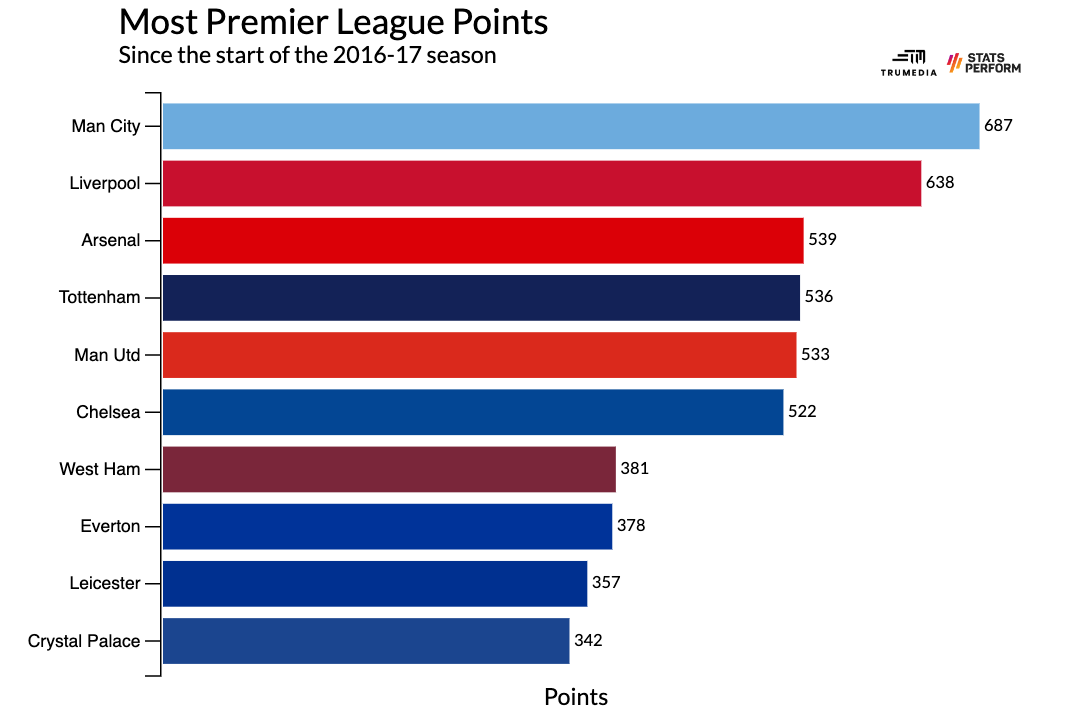

Of the past six Champions League finals, half have been won by English sides, and four featured English runners-up. Since Jurgen Klopp and Pep Guardiola came to England, the Premier League has become the premier league. Klopp’s Liverpool and Guardiola’s Manchester City dominate Europe, and the two managers’ ideas shape the sport.

With Klopp leaving Liverpool at the end of the season, the Sunday match at Anfield could be the final chapter in modern soccer’s defining rivalry between two of the greatest coaches ever. The four highest point totals in Premier League history (and six of the top eight) were produced by Klopp and Guardiola teams.

It’ll be a long time until we see two teams as good as Liverpool and Man City at the same time again. So, ahead of Sunday’s potential title-decider, let’s take a look back at how both managers shaped the Premier League — and each other.

How Klopp changed the Premier League

To get a sense of the environment that Klopp was walking into back in 2015, all you need to do is watch this video:

The Premier League had emerged from what is colorfully known as the “s— on a stick” era. During the previous period of dominance in the mid-to-late aughts, Liverpool manager Rafael Benitez and Chelsea manager Jose Mourinho prioritized more reactive approaches, where defensive organization was the main principle and everything else came second. The teams were great, but the games were frequently terrible to watch.

“Football is made up of subjective feeling, of suggestion and in that, Anfield is unbeatable,” Argentina World Cup-winner Jorge Valdano said after Chelsea and Liverpool played in the 2005 Champions League semifinals. “Put a s— hanging from a stick in the middle of this passionate, crazy stadium and there are people who will tell you it’s a work of art. It’s not: it’s a s— hanging from a stick.”

At the moment of Klopp’s arrival, the best teams had stopped playing such terrible, uninspiring soccer, but the big English clubs were still chasing the rest of Europe. Teams like Arsenal prioritized slick passing, but then it would fall apart in European competition when they came up against more talented teams who were both better at passing and more organized.

Broadly, Premier League clubs were inching toward a more defined continental style, but they were worse at the continental style than any of the teams on the continent. So, for the first half of the decade, England’s best teams weren’t tactically distinct — they all sort of did a little bit of everything, without committing to one thing.

Of course, Klopp’s whole thing is one thing: high pressing, vertical passing, constant running, making sure the fans feel something. If you’ve seen Liverpool play at any point since 2016, you know they do that. But let’s put some numbers on it.

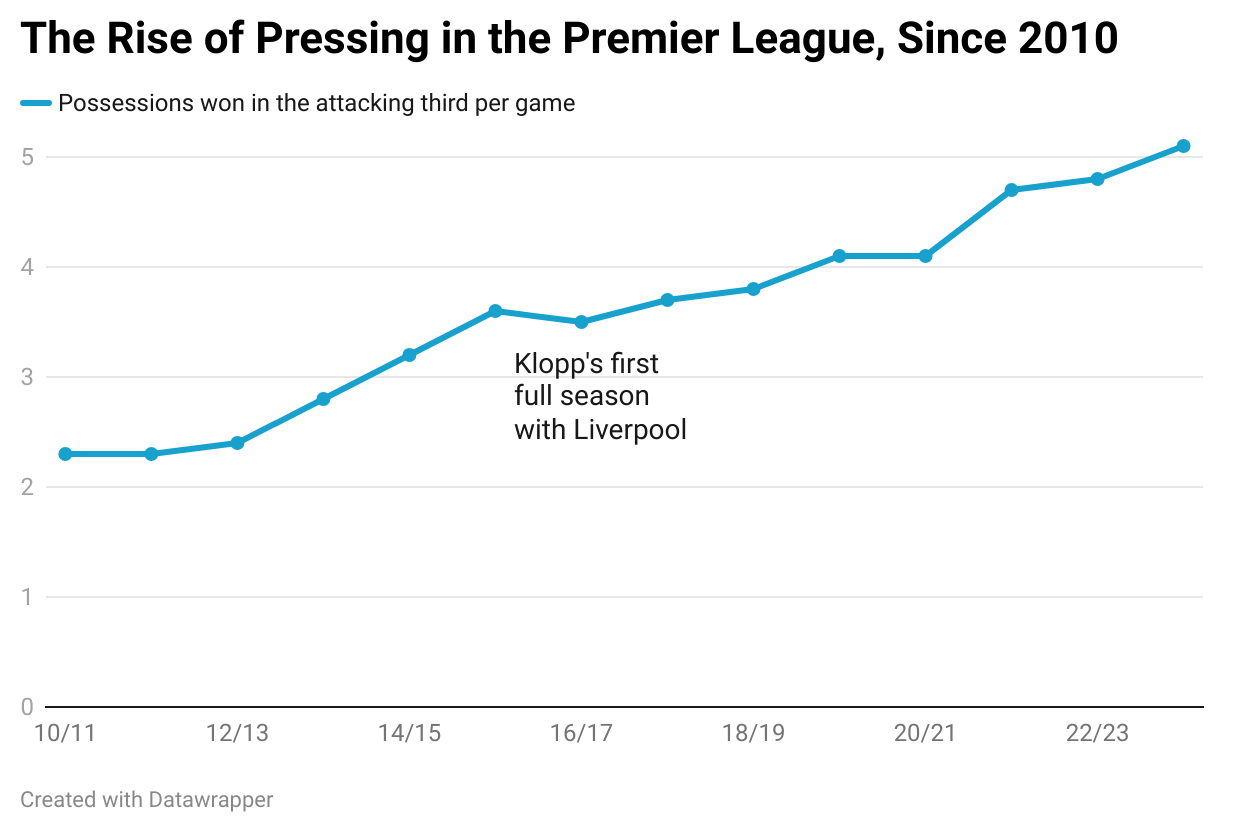

Per Stats Perform, only two Premier League teams since 2010 have won possession in the attacking third more than 250 times in a season: Liverpool in 2021-22 (287 times) and Liverpool in 2019-20 (252 times). Everyone is familiar with pressing now, the concept of collectively pressuring an opponent to try to win the ball as quickly as possible — it’s the most ubiquitous tactical strategy in the modern Premier League. In fact, teams can largely be defined simply by how much they try to press.

However, this just wasn’t true when Klopp came to the league. Among the top 50 pressing seasons in the Premier League since 2010 — as defined by number of possessions won in the attacking third — just four of them come from seasons before 2016-17, and one of those comes from Klopp’s partial first season with Liverpool in 2015-16.

Behold, the Klopp Effect:

In Klopp’s first full season with Liverpool, the average Premier League team won possession in the attacking third 3.5 times per game. In his eighth and final full season, it’s all the way up to 5.1.

Such is the ever presence of the approach that relegated Leeds United ranked fourth in the league in possessions won in the attacking third last season. The high press is now an option for anyone — anywhere in the table.

How Pep changed the Premier League

Despite England’s struggles in Europe, plenty in England still doubted the credentials of Europe’s most successful manager when he arrived. Sure, he created two superteams at Bayern Munich and Barcelona that dominated possession to never-before-seen levels and frequently annihilated Premier League opposition in the Champions League, but what would happen when he faced Stoke City and West Ham United week after week?

Before Guardiola managed his first game at City, former Manchester United manager Sir Alex Ferguson tried to warn the Spaniard about what he was getting himself into. “Man City have made a real coup in getting him, but Pep won’t find it easy — English football is not easy,” he said. “Every foreign coach that has come to England will tell you that. Arsene Wenger was talking about that a few months after coming and even Jose Mourinho was. Pep will be a success, but I don’t think he’ll ever replicate what he did at Barcelona because that was a high standard — they were the best.”

In Guardiola’s debut season at Man City in 2016-17, he had no problem implementing his possession approach. City led the league, by a wide margin, by controlling 65% of the possession in their matches. It just didn’t contribute to wins in the same way we were used to seeing. They finished third, 15 points back of first. To some, this proved their skepticism of the Spaniard warranted. Pretty passing worked outside of the British Isles, but it would never win you titles in England.

Former Manchester United defender Gary Neville doubted Guardiola’s possession-heavy approach. “I just wonder whether they can play that way,” he said. “That’s the fascinating thing over the next 12 months. Can you play that way, with those players and win this league? That will be the real test.”

Former Manchester United (sensing a theme here?) goalkeeper Peter Schmeichel took it a step further, calling Pep “an arrogant man” for not shifting his approach in the face of some poor results. “That is a man saying: ‘I know best. My way of playing football is the best.'”

Amidst all of the criticism that built up across the 2016-17 season, Guardiola held firm to some elementary logic. “I won 21 titles in seven years: three titles per year playing in this way,” he said. “I’m sorry, guys. I’m not going to change.”

He didn’t change — and he won everything. In his second season in England, Manchester City won 100 points, the most of any team in Premier League history. The following year, they won 98 points, then the second-most points in league history. Last season, of course, they won the Champions League, Premier League, and FA Cup. They’ve won the league three years in a row and, were it not for Liverpool ripping off a 99-point season in 2019-20, they’d be challenging for a seventh straight league title.

For all of Liverpool’s success under Klopp, it’s Pep’s City at the top, then Klopp’s Liverpool … and then everyone else:

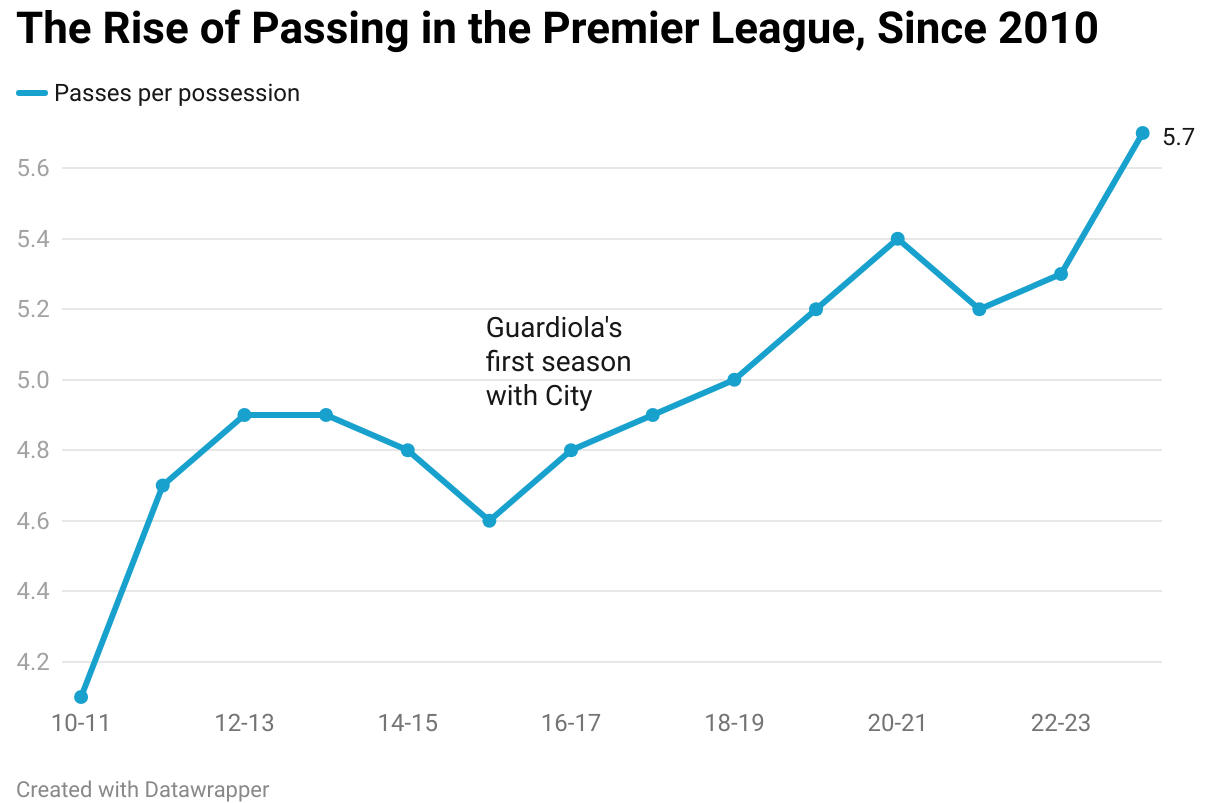

The funny part is that City’s success didn’t come from Guardiola conceding that English soccer was in fact different. No, their success coincided with them controlling even more of the ball.

In 2016-17, City led the league with 6.6 passes completed per possession. In every season since, they’ve been at 8.4 or above — all of which make up the top seven seasons for any club since 2010.

The rest of the league has followed suit, too:

Eight years ago, conventional wisdom was that you couldn’t pass your way to a Premier League title. Today, it’s pretty clear that if you can’t pass, you can’t win anything.

How Klopp and Pep changed each other

There’s an inherent tension to all of this. The rise of pressing and the rise of passing seem like they should cancel each other out. If teams are harder to pass against, then passing numbers shouldn’t be on the rise. If teams are better at passing, then pressing numbers should be on the decline. Instead, teams have become more effective at both pressing and passing. Better passing can be negated by better pressing, which can be negated by better passing, which can be negated by better pressing, and on and on.

That push-and-pull (press-and-pass?) is what has made the Liverpool-City rivalry so compelling. One team wanted to throw their games into complete chaos; the other wanted to suck the air out of every match they played. But over time, they’ve both become more like each other.

With Liverpool, the shift is much more obvious. The team really didn’t take off until they figured out how to become more effective in possession. You simply can’t create enough goals out of pressing transitions to win the Premier League. Plus, once teams know you want to press, they’re not going to give you as many opportunities to press against them.

The first solution for Liverpool was to build a sturdy, unspectacular midfield and give the two full-backs the keys to final-third possession. Andy Robertson and Trent Alexander-Arnold currently rank tied for first for the most assists by a defender in Premier League history. With those two leading the way, creatively, Liverpool won the Champions League and Premier League in consecutive seasons.

The step after that was to plug Thiago — a Guardiola favorite at Bayern — into the midfield along with the two full-backs. To my mind, this produced Liverpool’s best-ever team in 2021-22 — they won the two trophies Klopp hadn’t yet won (Carabao and FA Cups) and were within a couple inches of also winning the Premier League and the Champions League.

Klopp’s team hasn’t really eased off the idea of pressing on the whole. It has ebbed and flowed across seasons, but remains intense. That system creates such a high floor, but their steady improvement in possession is what’s turned them into one of the best teams in the world. In Klopp’s first two full seasons with Liverpool, they averaged 6.1 passes per possession, and they haven’t been below 6.5 in any season since.

While Liverpool struggled with the lesser teams in the Premier League, City’s main struggles were with Liverpool themselves. Across their first 10 matches against each other in England, Liverpool won five, City won two and the rest were draws. This is at a time, too, when City barely did anything other than win.

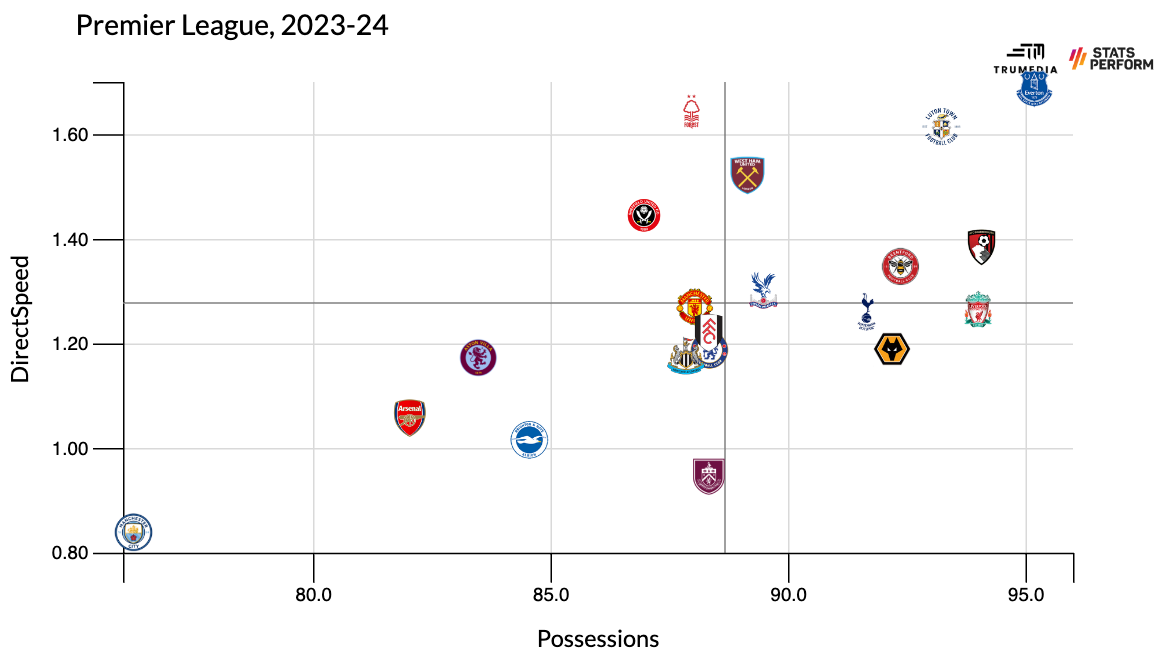

So, in some ways, the development of City can be seen as a direct response to Liverpool. With each passing season, Man City have become more and more careful with the ball. They’re moving the ball more slowly upfield, year after year, and their games feature fewer and fewer possessions. This year, they’re moving the ball upfield at 0.84 meters per second and their games feature 76 possessions per team — both lows of the Guardiola era and lows in the Premier League this season:

Liverpool killed City in transition moments; City have done everything they can to kill transition moments. Despite having fewer possessions than ever before, though, City are also winning possession in the attacking third more than ever before: 7.1 times per match, a mark that over a full season would eclipse Liverpool’s two best totals since 2010.

Although Pep’s City are further than ever from Klopp’s heavy-metal Liverpool, they’re also using Klopp’s main tactic — winning possession in the attacking third — selectively and more effectively than ever before. Liverpool, meanwhile, still live in chaos — only two teams average more possessions per match than their 94, but within that chaos, they still find more moments of control than they used to.

And so, on Sunday we might see Liverpool score a goal from a complex, extended passing movement. We could see City score from a long pass, a high turnover and quick-hit move toward goal. Or we could see the exact opposite. Eight years on, Klopp and Guardiola have pushed and transformed each other as much as they’ve transformed the league around them.

These games have always been must-watch, for their contrasting styles, for the stakes, for the constant struggle from both teams attempting to impose their will. That’ll be no different on Sunday: Liverpool are first and City are second, just one point apart. This is, once again, the most important game of the Premier League season. But it’s different from all the others in one particular way: we’ve never seen anything like this rivalry, and after Sunday, we might not see anything like it ever again.

Credit: Source link