Normally, this would not be good advice, but just trust me on this one: Don’t listen to Liverpool manager Jurgen Klopp.

Over the past weekend, the typically wise and well-spoken German claimed that Liverpool’s goal for the upcoming season was to qualify for the Champions League and that “it looks like City in the end will be the champion.” He’s right that Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City are the favorites to win the Premier League, according to the predictive models and betting markets. They have, after all, won four of the previous five titles.

But the other team to win one over that stretch was Klopp’s own club, and in two of those other seasons they landed in second place by just a single point. Six of the eight best seasons in Premier League history come from Klopp- or Guardiola-coached clubs over the past five years: three for Liverpool and three for City. With some better timing, Liverpool might even have more titles than City. Given how many games they’ve won over the past five seasons (131 to City’s 146), it really does seem like one league title is the absolute minimum that Klopp & Co. could’ve claimed. No wonder he sounds so fatalistic so close to the start of the season.

However, even the most dominant teams change from year to year due to roster churn, injuries, player performance gains, player performance declines, opponent adjustments and all the randomness inherent to trying to kick a round ball with a misshapen foot. So, with the sides set to square off this weekend in the Community Shield, let’s take a look at all the different ways Liverpool and City dominated last season — and what it says about what we should expect from the new campaign.

Ball dominance

One of the ways that Liverpool came to challenge Manchester City so consistently was by becoming more like Manchester City. In Klopp’s first half-season, Liverpool produced a field tilt (final-third passes completed by your team, compared to the number of final-third passes completed by the opposition) of 59%. This past year, that number rose all the way up to 69.4%, the highest the club has produced in the Stats Perform dataset, which extends back to the 2008-09 season.

City, meanwhile, have fended off Liverpool so consistently by becoming even more like City. In Guardiola’s first season, their field tilt was 66.9%. This past year, it was 75.6%, the highest number ever recorded in the Premier League.

In fact, only 10 teams have played at least two thirds (66.6%) of their matches in the opposition third: all five editions of Guardiola’s City sides, Klopp’s last three Liverpool vintages, and Maurizio Sarri’s one season with Chelsea in 2018-19. While all of the City and Liverpool teams continued to heavily tilt the field from one season to the next, Chelsea’s field tilt dropped from 66.7% to 61% the following season.

However, that only happened after a managerial change, from Sarri to Frank Lampard. Given that Klopp and Guardiola aren’t going anywhere, it would be shocking if either side didn’t dominate the territory battle again in 2022-23. Sure, the introductions of Erling Haaland at City and Darwin Nunez at Liverpool, two more-traditional strikers who won’t be as involved in possession play as the players they’re replacing, suggest a willingness from both teams to cede a bit of ball control, but their percentages here should still lead the league.

Dangerous possession

Controlling the final-third raises your floor. It’s really hard to be a below-average team if the majority of your matches are spent in the other team’s defensive third. But we’ve seen plenty of teams over the years who turn that kind of dominance into a barrage of low-quality shots for themselves and a few high-quality chances for their counter-attacking opponents. See: the aforementioned Chelsea under Sarri.

Other sides — think the peak Jose Mourinho teams of the past, or the Antonio Conte teams of the current era — sacrifice some of the final-third control in order to dominate the penalty area. They limit access to their box by not risking as many players forward, and they get easier access to the opposition area by drawing their opponents out of their own third.

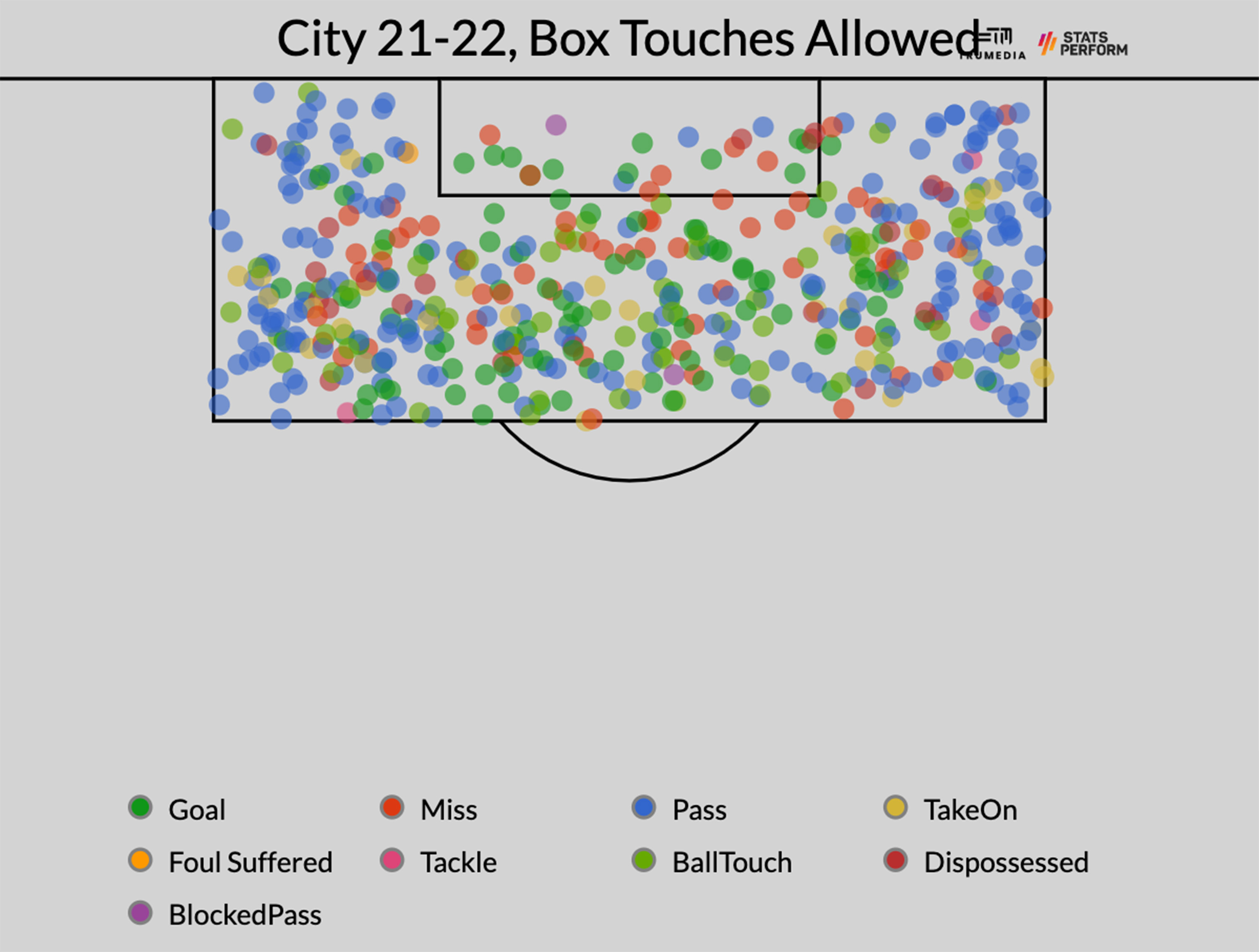

The truly dominant teams that sustain excellence year after year, though, are the ones that can do both. Last season, City allowed the fourth-fewest opponent touches in the box of any Premier League team we have data for:

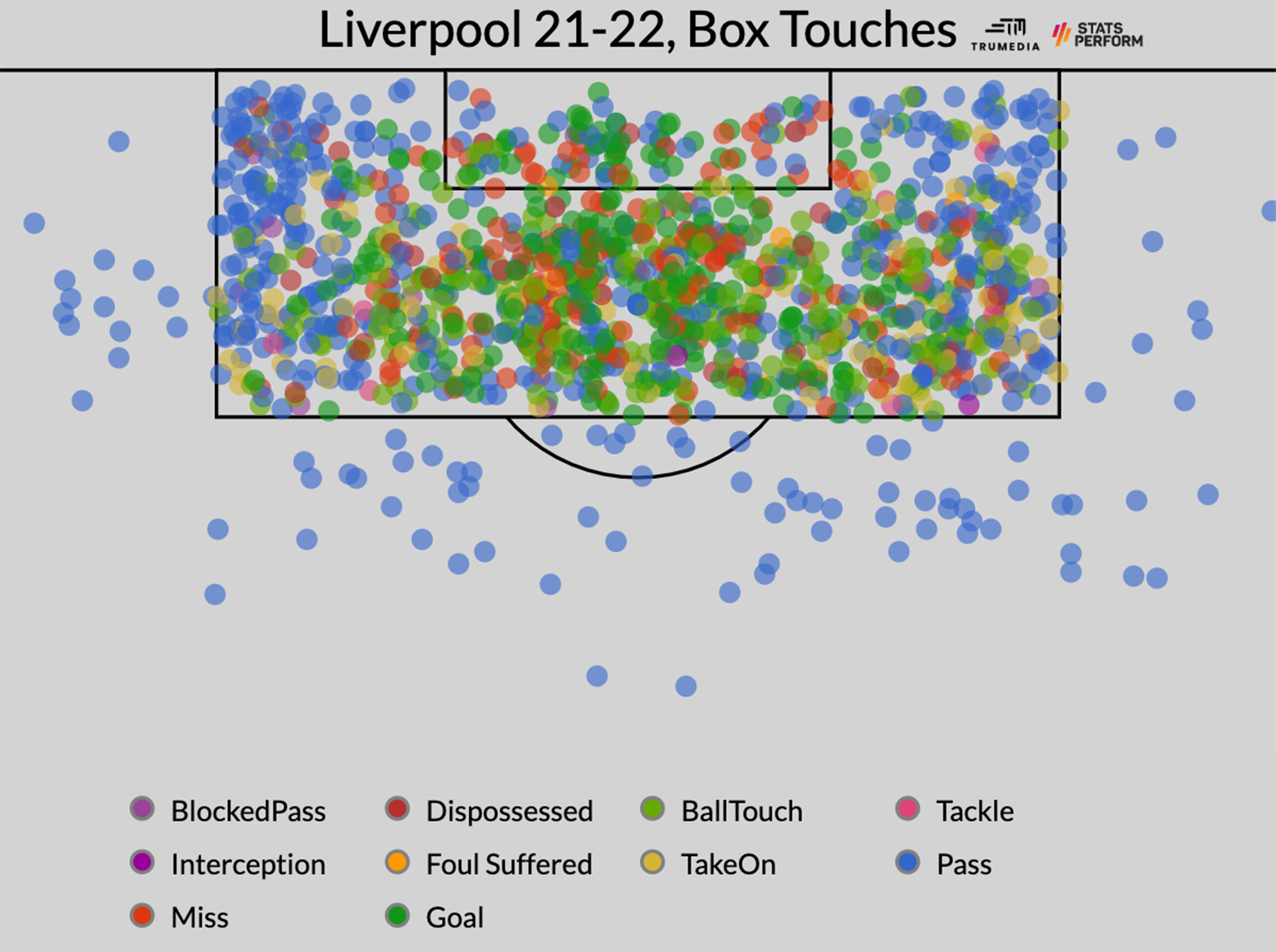

On the other side, they took the second-most touches in the opposition penalty area in the database, while last year’s Liverpool were fourth:

Taken together, City managed 28.8 more touches in the penalty area per game than they allowed — the second-biggest differential for a singleseason. Liverpool, meanwhile, were fifth at plus-23.6. The top 10 is 90% City: all five Guardiola seasons, plus the title-winning teams of Roberto Mancini (2011-12) and Manuel Pellegrini (2013-14), along with Pellegrini’s 2014-15 side.

Much like with ball control, Liverpool’s dominance in the most dangerous area of the field has steadily improved under Klopp — before reaching a new level last year:

– 2015-16 (games under Klopp only): plus-11.7 penalty-area touches

– 2016-17: plus-17

– 2017-18: plus-17.4

– 2018-19: plus-17.1

– 2019-20: plus-17.8

– 2020-21: plus-18

– 2021-22: plus-23.6

Outside of Klopp’s six full seasons at Anfield and the nine aforementioned City sides, the only other Premier League team to reach a penalty-area-touch margin of plus-17 or more was Carlo Ancellotti’s title-winning Chelsea team in 2009-10. They hit plus-17.8 and then dropped down to plus-14.2 the following season — this time without a managerial change. So while that suggests the potential for a drop-off for both Liverpool and City, what’s much more likely is that they sustain a similar level of domination in the most dangerous area on the field.

With Liverpool leaping up to City’s level last season, they seem like the bigger candidate for a drop-off, but only back down to their previous level, which is still higher than any team other than City.

However, City did lose Raheem Sterling, who tended to lead the team in penalty area touches per 90 minutes year after year, and Gabriel Jesus, who was fourth on the team last season by the same metric. To be clear: getting touches in the box is a skill — arguably Sterling’s best skill — and City are betting hundreds of millions of pounds, it seems, on Jack Grealish and Erling Haaland providing the same kind of consistency.

The balance of chances

Last week, Elliott McKinley of American Soccer Analysis reconfirmed — in addition to a number of new findings — the predictive power of Expected Goals (xG). Looking at the 14,608 games since the 2017-18 season across the Big Five leagues — and removing all of the matches from the 2020-21 season played mostly in empty arenas — he found that a team’s xG ratio significantly better predicted a team’s future results than their shots-on-target ratio, shot ratio, goal ratio, and points-per-game rate — in that order. Creating great chances and suppressing them on the other end is, in the long run, how you win soccer games.

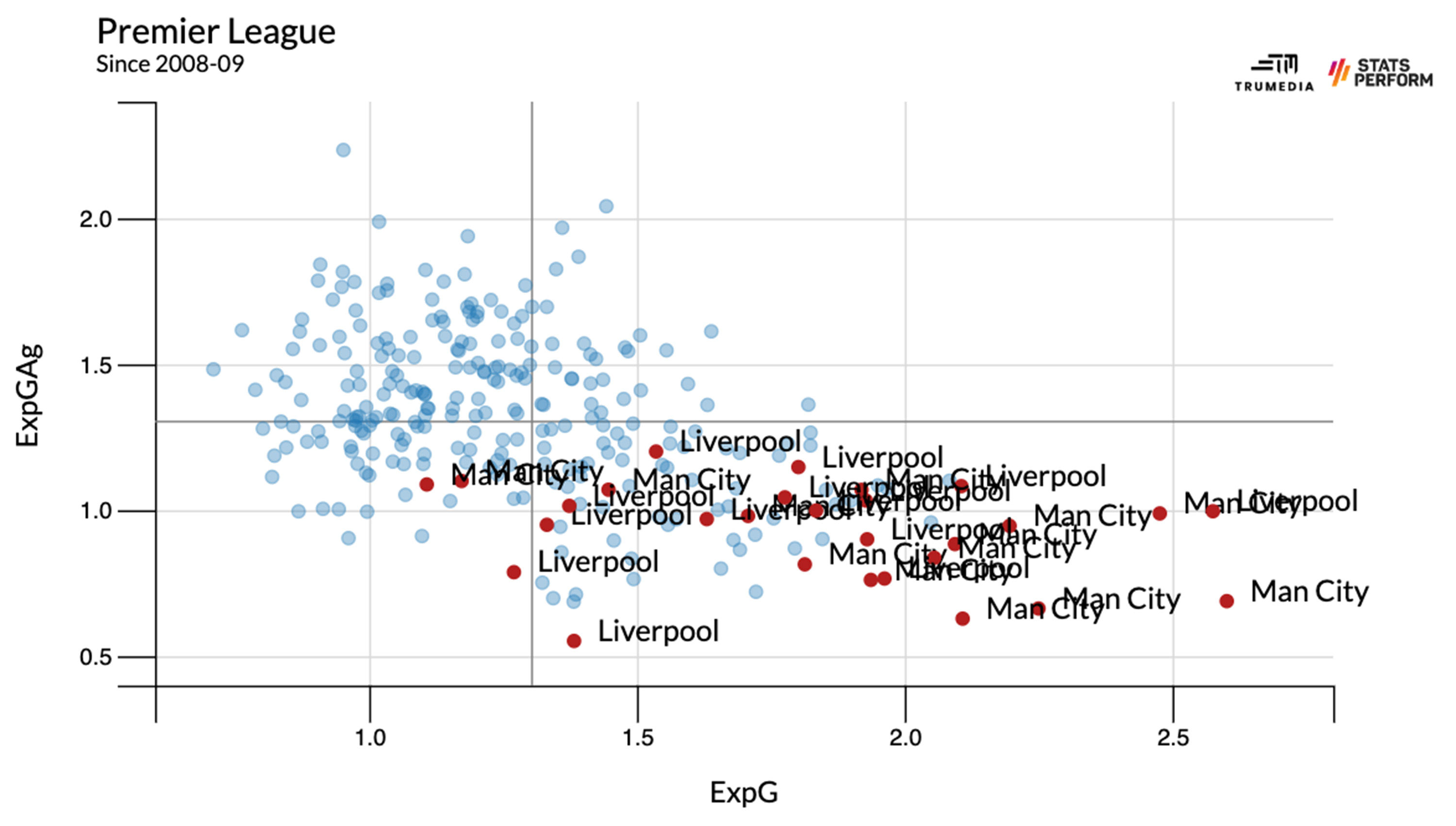

While McKinley’s work looked at the in-season predictive power of the metric, it stands to reason that xG would also be more reliable of a predictor from season to season than the other metrics, too. During Stats Perform’s advanced-data era, Manchester City produced the best-ever xG Premier League differential last season (plus-72.7), while Liverpool were third-best (plus-60.)

This chart contains each individual Premier League team season since 2009. Last season’s City are the dot in the bottom right corner; Liverpool are the dot right above it.

To put this another way, there are a lot of teams that put up the kinds of point totals that Liverpool (92) and City (93) did last season — eighth and tied-for-sixth most in Premier League history, respectively — on the backs of something unsustainable. It’s why most teams don’t do it; this kind of season-long excellence usually requires something that’s near impossible to repeat. It could be a career year from multiple players at the same time, a succession of well timed one-goal wins, an injury-free season, or a year-long run of bad finishing from the opposition. But neither of these teams are one of those teams.

The difference between the two is that City have been at this level of historic dominance across the board — tilting the field, living in the opposition box, and dominating the balance of chances — for the better part of a decade. Liverpool, meanwhile, just got there last season. But as we’ve seen with City, when you get that good at everything, you tend to stay that good. And that’s the only reference point we have for the rarefied air these teams currently occupy.

So, while Klopp is correct that City are the favorites to win the Premier League again, I’m not sure that’s the right framing for the season we’re about to watch. I think the most likely outcome is that both teams, once again, are among the best teams we’ve ever seen. And if that’s the case, the most likely outcome for the 2022-23 season is that it’s decided by something — a hot streak, a couple of bad calls, a few unlikely deflections, one or two unforgettable individual performances — that is impossible to predict.

Credit: Source link