Whiffs of fragrant roses, jasmine and bergamot are rising from the flask.

“You smell those flowery tones? These are the basis of all women’s perfume,” says Guy Delforge, spraying a bottle of his own creation.

From his workshop in the citadel perched above the Belgian city of Namur, he ingredients from around the world to craft his signature scents.

A perfumer for 34 years, Mr Delforge, 78, notes a shift in the industry with customers pushing for natural, sustainable fragrances.

“Perfumes have existed for 5,000 years and the scents haven’t changed much,” he says.

“But today… customers want to know the artisan making their perfume. It reminds me of when I started selling perfume from my garage in the 1980s.”

Millennials are the driving force behind the trends reshaping the sector, according to beauty industry magazine Cosmetics Business. It says they want more transparency and more gender-neutral scents – often based on citrus smells.

Citrus is one of the seven families of smells; with floral, chypre (oak moss with fruity notes), and amber often regarded as female scents, while fougère (lavender/woody) woody and leather are often grouped as male scents.

“A person is born liking one specific scent family and that preference rarely changes,” says Mr Delforge, whose eponymous line carries 40 eau de parfums, with each 100ml bottle costing €51 ($57; £45).

In the heart of Namur’s old city, Romain Pantoustier, “le nez” or nose in French, provides customers with transparency about the ingredients used in his perfumes.

The glass bottles of his Nez Zen range are refillable, the perfumes are gender neutral and also vegan, avoiding the musks from deer and other animal-derived produce were used in the past. Deer musk is specifically a secretion produced from the scent gland of the male musk deer.

An international convention covers the trade in musk but most products in the perfume industry now contain synthetic versions of the previously used animal scents. This is the one area where millennials definitely prefer synthetic ingredients instead of natural ones in their perfumes.

In the past other animal-derived ingredients used in perfume included ambergris from sperm whales, produced by the mammal’s digestive system, and castoreum – a secretion made by beavers.

Synthetic versions of lily of the valley – one of the world’s most expensive flowers – are also available. Such use of synthetics can also make products more cost effective, but often make use of petroleum and its by-products.

Mr Pantoustier, 40, says nature is the basis of his inspiration. He quizzes each customer on their favourite colours, textures, feelings and hobbies before recommending a fragrance. He also designs tailor-made perfumes for individual clients for €1,500.

“When a person comes in I ask them what they like. I use words to create a mapping in my head to guide them through my fragrances,” he says, while drinking water flavoured with an edible scent. “Who am I to say what gender a scent should have?”

The Frenchman founded the Belgium-based business in August 2016 with his wife Aurélie, after working as a scent designer for some of Europe’s biggest perfumers.

“I wanted to move away from a more industrial approach to perfuming, and get back to a much more artistic and emotional approach.”

Across the Atlantic, Charna Ethier also used to work for large firms in the fragrance sector, before founding the Providence Perfume Company in 2009.

“I noticed there was a demand for natural botanical smells that was being neglected,” she says. “There’s lots of greenwashing in the sector.”

Inspired by her childhood on a farm on the US east coast, she says many modern shoppers are so used to synthetic smells in perfumes they do not know what natural options smell like.

Ms Ethier, 44, distils fruits, flowers, wood and plants in a pure alcohol spirits base to create her natural perfume line. Providence Perfume’s website says the final products contain no synthetics, petrochemicals, fragrance oils, dyes, parabens, phthalates or chemical fragrances.

All her perfumes are also gender neutral, something she says is particularly appreciated by her younger clientele.

“Millennials don’t want to wear their mom’s perfume. They want to smell different, like leather, crushed herbs and smoke,” she explains. “I get a lot of women saying they don’t want to smell like flowers.”

Gender fluid fragrances have surged in popularity in recent years: 51% of all perfume launches in 2018 were gender neutral, up from 17% in 2010, according to industry figures.

At Coty, the world’s largest fragrance firm, with 77 brands including Chloé, Hugo Boss and Gucci, trends for more gender fluid, sustainable and exclusive products are closely monitored.

“The companies who are winning are the industry leaders that have refreshed their proposition, and new brands because millennials are brand agnostics,” says Laurence Lienhard, Coty’s vice president of consumer marketing insights.

Ms Lienhard says Coty has also worked hard over the past five years to use less packaging and more organic ingredients.

“It’s time for bigger brands to take a stand – so we are working on it more and more.”.

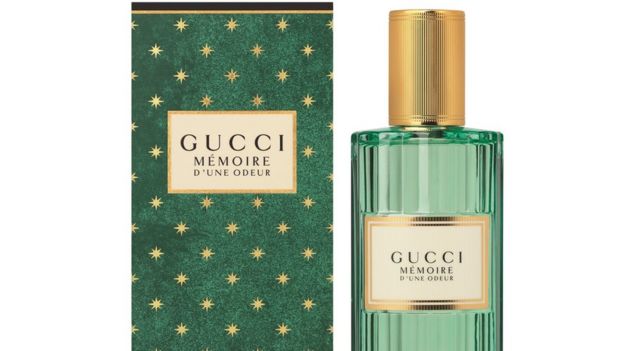

Ms Lienhard adds that demand for gender fluid, universal scents is particularly strong in English-speaking countries. It released its first unisex offering, Gucci Mémoire d’une Odeur, earlier in 2019. The scent is marketed in both men’s and women’s sections of perfume stores.

Back in Belgium, Mr Delforge peruses through the French Perfumers Society’s official perfumes guide, which he calls “the bible” of perfumery.

“This book describes all the different scents, but two perfumers could choose the same ingredients and create a different smell. It is like different chefs making different types of mayonnaise. It’s still mayonnaise but it doesn’t taste the same,” he explains. “Perfume is the same.”

Credit: Source Link