Last year, I published a book that was, among other things, about how most European soccer clubs are terrible at making decisions. There’s all kinds of data out there now that should help teams understand the varying levels of uncertainty in all of the decisions they’re making. We’ll never totally quantify everything that happens on a soccer field, but it’s quite easy to dig deeper than just wins and goals for anyone who wants to try.

You know, maybe you shouldn’t fire that coach; sure, you’re losing week after week, but you’re really just getting unlucky. Or maybe you don’t need to drop $80 million on that new striker because he converted his shots into goals at an unsustainable rate and you’ve already got a guy on the roster who suffered through a finishing slump, but who’s also doing the main thing that predicts future goals: getting on the end of lots of good chances.

Over the past couple of years, however, it did seem like teams were slowly getting smarter. Since the beginning of the pandemic, there appeared to be fewer rash firings, managers who seemed unlucky to lose their jobs were quickly getting hired elsewhere, clubs focused on acquiring younger players, and there were just fewer obviously misguided big-money transfers. From a selfish point of view, this was not a good development for someone who’d written a book about how the opposite had been true.

And then, well, this summer happened.

Premier League clubs spent more than £2 billion on transfers in a single window for the first time ever — breaking the previous record, set last summer, by more than £500 million. (FIFA confirmed that clubs spent nearly £6bn in the window.) Given that you’re just giving money to another team in order to break a player’s old contract so you can then sign said player to a new contract, ballooning transfer-fee payments don’t really correlate with “teams getting better at making decisions.”

So what happened? Well, if you found a $20 bill on the street, would you invest it in an index fund? All of a sudden, the Saudi Premier League infused the player market with an extra billion dollars. A year ago, that money didn’t exist.

How the PIF came out of nowhere

The SPL transfer window didn’t bang shut on Sept. 7, but instead whimpered to a conclusion. The Mohamed Salah situation between Liverpool and Al Ittihad never got testy and never really even came close to happening, while no genuinely “big” names changed teams in the period between the close of the European window and the Saudi window’s closure a week later. But that’s not to downplay the overall impact of the Public Investment Fund’s, um, very public investment in Saudi Arabia‘s national soccer league.

The major story coming out of every transfer window continues to be the increasing financial dominance of the Premier League. This time around, Premier League clubs spent more money on transfer fees than all of Europe’s four other major soccer leagues, combined. The net spend of the Premier League — transfer fees paid minus transfer fees received — also landed north of £1bn, per analysis by Kieron O’Connor for his newsletter, The Swiss Ramble. Among the other four leagues, only France‘s Ligue 1 also spent more on player purchases than sales, and their net spend was just £19m.

Combined, the German Bundesliga, Italian Serie A, Spanish LaLiga and Ligue 1 teams made a £531m profit from the transfer market this summer. Again, that’s in comparison to a £1bn+ loss made by Premier League clubs. Heck — tiny little Bournemouth had a higher net-spend this summer than every team outside of England other than the one that’s bankrolled by the nation of Qatar. The spending gap between the Premier League and everyone else is only getting wider. It’s getting ridiculous and at some point, this isn’t just can’t to continue to hold.

Everyone else in Europe, that is.

After the Premier League, Saudi clubs spent more on transfer fees (£834m) than any other league. That’s still a ways away from the £2bn spent by teams in England, but the big difference between the two leagues — for this particular line of analysis, at least; there are lots of big differences between the two leagues — is that Premier League teams also made a ton of money from transfer fees received. The Saudi league did not.

Adjusted down to net spend, the SPL and the EPL were not that far apart. Saudi teams spent £776m more than they made from player transfers. Compared to all of last year, both the summer and winter windows, that’s just a minor 1,092% increase in spending for Saudi clubs. All four of the PIF-owned clubs ranked in the top 11 for net spend worldwide. Al Hilal’s leading net-spend (£306m) was nearly double Chelsea‘s second-highest mark of £175m. Al Ittihad ranked 11th, but their most expensive acquisition was probably Karim Benzema, who came over from Real Madrid as a free agent. When accounting for the contracts and transfer fees, SPL clubs might have even outspent Premier League teams.

Why this summer was weird

Despite all of that, the Saudi League still hasn’t really become a competitive threat — yet. Through at least one transfer window, it’s pretty simply been an economic boon for the established order of European soccer.

Per the rating system employed by the consultancy Twenty First Group, the Premier League signed 28 of the 100 best players to move teams this past window. Second-most goes to SPL clubs, who nabbed 15 of the top 100 players. However, per TFG’s ratings, Saudi clubs only signed two of the 100 best under-26 players to change clubs this past summer.

In other words, the SPL has provided a billion-dollar cash infusion to European soccer without any strings attached. They’ve paid well-above-historical rates for aging players whose clubs were happy to clear off their wages and get $30-something million from their departures. The same goes for standout players on midtable teams who didn’t have much of a market among any of the bigger clubs across Europe. The European clubs all wanted these moves to happen; we know that, because they let them happen.

So what happens when $1bn just sort of randomly gets distributed across some of the biggest clubs in Europe, almost out of nowhere? Based on this summer, those teams will try to spend it all as fast as they can.

It’s here where I need to acknowledge that this becomes much more of a “vibes-based analysis.” It’s hard to trace which effects come exactly from the Saudi money, but it’s the biggest new variable that was introduced into the market this summer. Teams that weren’t given money by a Saudi club for one of their players are still affected by that money. A team flush with Saudi money might come and buy one of their players; the new market conditions created by that influx of cash might make the players they want to buy even more expensive; seeing the Saudi money, they might be willing to take more risks with the hope that the SPL will still be there to bail them out. But my claim is that teams have been incredibly inefficient and erratic this summer, the same summer when this Saudi money came out of nowhere. So, those things are likely related.

Let’s just take all of the top teams in the Premier League — Newcastle excluded, since they’re owned by the same fund that is funding most of the SPL spending.

Manchester City made one “classic Man City” move: acquiring Josko Gvardiol, a close-to-unanimous holder of the title of “best young center back in the world.” Most teams can’t afford to spend as much as City did for a player in that position, but City’s infrastructure makes a deal for a Bundesliga centerback less of a risk. Plus, they’re funded by sovereign wealth; their per-dollar spending efficiency isn’t what drives their success.

The rest of their moves were quite strange. They replaced Ilkay Gündogan with Mateo Kovacic, a good midfielder who is also a very different midfielder than Ilkay Gundogan. Then they acquired winger Jérémy Doku from Rennes and midfielder Matheus Nunes from Wolverhampton for a combined £105m. The 21-year-old Doku is a really promising young player with incredible physical talent, while the 24-year-old Nunes has probably been, at best, an average Premier League midfielder for Wolves.

Both players have traits that you can project future performance onto, but since when do City take such big-money risks on players like that? The whole point of being City is that you can acquire the finished product.

Arsenal, meanwhile, convinced themselves that Kai Havertz was a £60m+ midfielder even though he spent the past three years being a consistently frustrating center forward. They almost purely imagined a level of certainty that the first four games of the season have proven were never there.

Liverpool have probably handled the Saudi dislocation better than anyone. They moved on from Fabinho and Jordan Henderson for more than £50m, signing four new either young and/or cheap midfielders. Except, they also thought they’d set the British transfer record for Moisés Caicedo, a player with a single season of high-level performance in Europe for a team whose players notoriously perform worse once they leave. Caicedo instead held out to force a move to Chelsea, who inspired me to write an entire column about the reckless manner in which the team is being run.

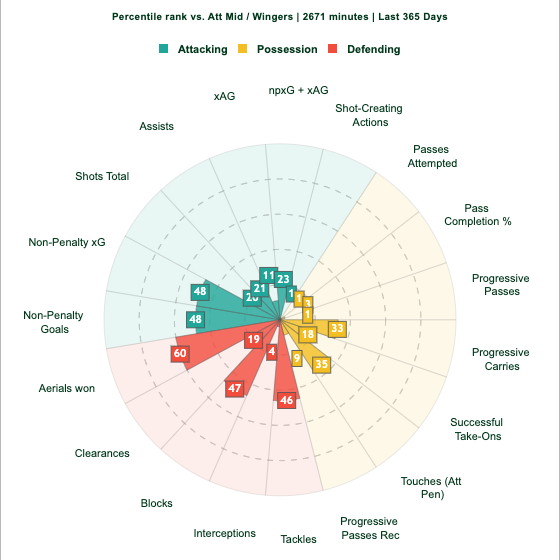

Manchester United spent nearly £120m combined on a forward (Rasmus Hojlund) with nine career goals in Europe’s Big Five leagues and a midfielder (Mason Mount) who had a year left on his contract and was coming off of the worst season of his career. Tottenham’s biggest signing of the summer was £45m on Nottingham Forest‘s Brennan Johnson, a forward who leaves very little statistical footprint on any of the matches he plays in:

Courtesy of FBCharts (data from Opta via FBref)

Even Brighton, the savviest club of them all, just spent the third-highest fee in club history on Carlos Baleba, a 19-year-old midfielder who’s accrued 539 total minutes as a professional soccer player.

Elsewhere in Europe, Paris Saint-Germain‘s net-spend was essentially identical to Chelsea’s despite the club mainly acquiring a cadre of utility men and secondary support pieces. And a year after the disastrous acquisition of one of the best attackers in the world (Sadio Mané) soon after he turned 30, Bayern Munich spent a club-record fee to acquire another one of the best attackers in the world (Harry Kane) soon after he turned 30.

This might all just be anecdotal. PSG are always a mess. Bayern Munich have entered a moment of vast institutional uncertainty. Manchester United are, too, always a mess. And the other Premier League clubs might all just be destined for a couple massive over-pays a summer now, given how much more money they have than everyone else.

But after the coronavirus pandemic stole matchday money from everyone for a season-and-a-half and finally put an end to the ever-growing revenue across European soccer, teams had to figure out how to keep their clubs afloat and competitive without just simply throwing money at the problem. So, perhaps this summer’s infusion of Saudi cash is what marks the beginning of soccer’s new post-COVID era, which looks a lot like the pre-COVID era: tons of money being spent, with only a loose relationship to what actually happens on the field.

Credit: Source link