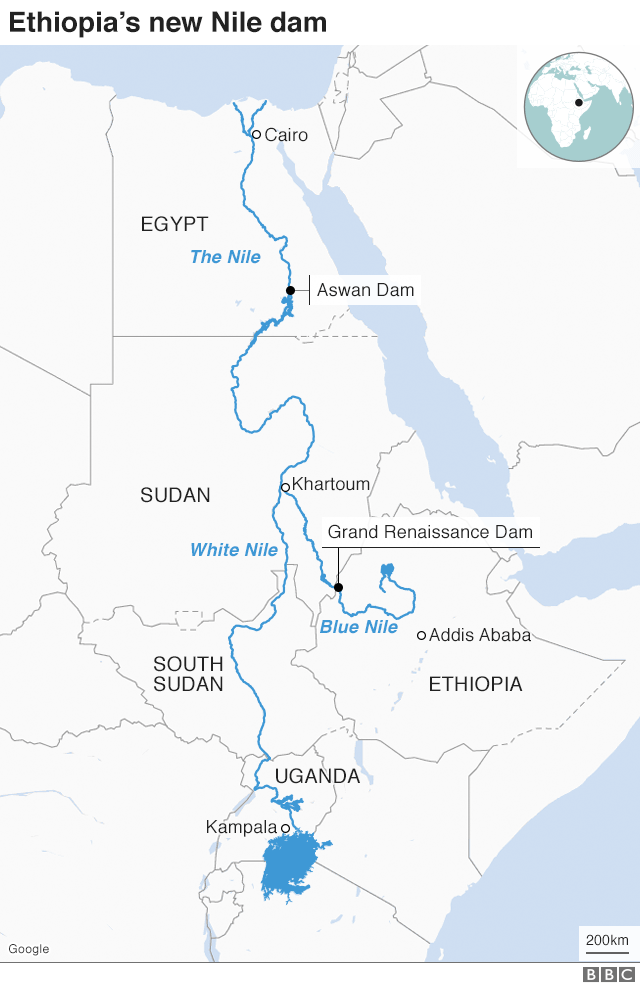

Satellite images taken between 27 June and 12 July 2020 show a steady increase in the amount of water being held back by the new mega dam, which straddles the Blue Nile in Ethiopia.

This has angered Egypt and Sudan, the two countries downstream of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (Gerd), as the timetable for filling it is yet to be agreed at deadlocked negotiations.

State media in Ethiopia has backtracked after reports that suggested the dam was being filled deliberately.

But this all gives the false impression that filling up the dam will be like filling up a bath – and that Ethiopia can turn on and off a tap at will.

Can’t it be stopped?

No. The reservoir behind the dam will fill naturally during Ethiopia’s rainy season, which began in June and lasts until September.

Given the stage that the construction is at “there is nothing that can stop the reservoir from filling to the low point of the dam”, Dr Kevin Wheeler, who has been following the $4bn (£3.2bn) Gerd project since 2012, told the BBC.

Explore the Nile with 360 video

From the start of the process in 2011, the dam has been built around the Blue Nile as it continued to flow through the enormous building site.

Builders worked on the vast structures on either side of the river without any problem. In the middle, during the dry season, the river was diverted through culverts, or pipes, to allow that section to be built up.

The bottom of the middle section is now complete and the river is currently flowing through bypass channels at the foot of the wall.

As the impact of the rainy season begins to be felt at the dam site, the amount of water that can pass through those channels will soon be less than the amount of water entering the area, meaning that it will back up further and add to the lake that will sit behind the dam, Dr Wheeler says.

The Ethiopian authorities can close the gates on some of the channels to increase the amount of water being held back but this may not be necessary, he says.

What’s the next stage?

In the first year, the Gerd will retain 4.9 billion cubic meters (bcm) of water taking it up to the height of the lowest point on the dam wall, allowing Ethiopia to test the first set of turbines. On average, the total annual flow of the Blue Nile is 49bcm.

In the dry season the lake will recede a bit, allowing for the dam wall to be built up and in the second year a further 13.5bcm will be retained.

By that time, the water level should have reached the second set of turbines, meaning that the flow of water can be managed more deliberately.

Ethiopia says it will take between five to seven years to fill up the dam to its maximum flood season capacity of 74bcm. At that point, the lake that will be created could stretch back some 250km (155 miles) upstream.

Between each subsequent flood season the reservoir will be lowered to 49.3bcm.

So why is Egypt unhappy?

Egypt, which almost entirely relies on the Nile for its water needs, is concerned that in most years of the filling it is not guaranteed a specific volume.

And once the filling stage is over, Ethiopia is reluctant to be tied to a figure of how much water to release as when fully operational, the dam will become the largest hydro-electric plant in Africa.

In years of normal or above average rainfall that should not be a problem, but Egypt is nervous about what might happen during prolonged droughts that could last several years.

Credit: Source link