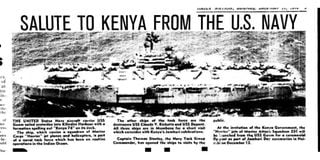

When US Navy aircraft carrier, USS Guam, sailed to the Kilindini harbour on Friday, December 10, 1976, the only thing Kenyans noticed was the formation spelling on its deck: “Kenya 76”.

The media was also duped and it all went as planned. There was a military fly-by – and diplomatically, Uganda had noted that Kenyatta had the US support. That was all he needed and Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, had approved the exercise.

During the celebration, at Nairobi’s Jamhuri Park, Foreign Minister Dr Munyua Waiyaki and Attorney General, Charles Njonjo watched the fly-by with amusement.

“(They) beamed at me from a distance, making thumbs up signal,” wrote US Ambassador to Kenya Anthony Marshall in a cable marked ‘Secret,’ describing the fly-by as a “resounding success”.

The ambassador, perhaps over the moon, also noted that the matter had not, as they plotted, got any publicity: “Press under-reported, and at no time alluded to participation as being anything but ceremonial.”

Besides Dr Waiyaki and Mr Njonjo, the only other civilian official who had been briefed was Defence Permanent Secretary Jeremiah Kiereini, who had eclipsed the sober-challenged minister, James Gichuru.

So serious was the threat that the US intelligence had worked behind the scenes to secure Nairobi without raising any alarm. That morning, and during the celebrations, Kenyans witnessed, and for the first time, US pilots make what was thought to be a “ceremonial fly-by”.

It wasn’t. They were sending a signal to Idi Amin – or whoever had intention of bombing Nairobi – that they were in town.

On November 23, 1976, Marshall, the US Ambassador, wrote a secret cable to the Bureau of Intelligence and Research of the State Department saying that “there is a possibility that some sort of terrorist/military attack in Kenya could occur on December 12.”

“While some type of attack cannot be ruled out, embassy believes that the use of Eastleigh Air Base by aircraft from USS Guam will afford far better security than use of Nairobi’s civil airport which past reports have indicated as possible target for terrorist activity,” Marshalls wrote.

Was there fear that Amin could bomb Nairobi’s Embakasi airport? Perhaps.

To forestall that, the embassy was to coordinate the security arrangements and send 12 AV-8 Harrier aircraft to Eastleigh as a standby. Initially, it had been agreed that the US and Kenya would make separate, but agreed upon, statements about the arrival of the three ships. Apart from Mr Njonjo and Dr Waiyaki, only a few other Kenyans were privy to the secret arrangements. Even the foreign ambassadors in Nairobi did not have a clue on what was happening.

The embassy made sure that even their own press officers remained mute on the subject.

“Unless otherwise instructed, the Embassy PAO (Public Affairs Office) will make no release but will be prepared to respond to press queries on basis of mutually agreed announcement,” Marshall had proposed.

The US Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, had on December 4, 1976 given instructions on how the matter should be handled in a confidential note that was sent to 24 embassies in the Indian Ocean zone. He told the envoys that if they are approached by the host officials or press following the announcement in Nairobi, they should say that this is a “routine” visit.

It had been agreed that two days before the celebrations, the Kenyatta government would issue a statement to Voice of Kenya (VOK) announcing that three US Navy Vessels, including the amphibious assault aircraft carrier, USS Guam, would be “visiting” the port of Mombasa at the invitation of the Kenya government.

It all went well and the statement had been given to the Kenya News Agency which also supplied the accompanying aerial photograph of the ship deck.

And just in case any journalist, or foreign government queried this visit; the US Embassy had been provided with some standard answers: “US naval visits to Mombasa are routine. Kenyan government invited US participation in its independence ceremony this year if availability of appropriate units permitted (and) given availability of USS Guam with compliment of aircraft suitable for a fly-by the US government decided to accept Kenyan invitation.”

The guidance was also sent to the US ambassador to Uganda, Richard Ellerkman – just in case Idi Amin asked.

He was told: “If Uganda queries suggest presumption of hostile intent behind US actions …state that fly-by is ceremonial in nature and in no way directed to any other country.”

For his part, the US Ambassador to Tanzania was asked in a secret cable from the Department of State to, in private conversations, express hope that the fly-by will not be “misinterpreted as being anything other than a small gesture on our part to accommodate (Kenyan’s) desire to embellish their independence anniversary ceremony.”

Kenya’s ill-equipped air force

The USS Guam was accompanied by a guided missile destroyer, USS Claude V. Ricketts and a destroyer, USS Dupont.

By then, Kenya had an ill-equipped air force with a handful of what diplomats called “antiquated British-built aircraft” while Idi Amin had managed to secure 30 Soviet-built combat aircraft including MiG-17 and MiG-19 fighters. Kenya, by then, was still negotiating with the US to get some second-hand F-5 fighters and had sent Mwai Kibaki and Vice President Daniel arap Moi to negotiate.

But as Idi Amin continued to make threats following the July 3, 1976 Israeli raid on Entebbe, Jomo Kenyatta was getting worried that Kenya was badly exposed – and only a show of pseudo-might could work, in the interim.

Back in Washington, the Department of State spokesman had been drilled on how to answer questions, dodge others – and divert queries to Pentagon.

For instance: What type of aircraft will be used in the fly-by and how many aircraft will be involved? His answer would be: “You would have to ask defence for the technical details, but for your information I understand that the aircraft involved will be AV-8 Harriers, a vertical take-off jet…”

Question: “But isn’t it a bit unusual that three US Navy ships and a complement of aircraft just happen to be in Mombasa during the Kenyan Independence Day celebrations?”

Answer: “Well, in the first place it is not unusual for US Navy ships to be in Mombasa. US Naval visits to Mombasa are a routine occurrence.” He would also say that it is Kenyans who invited them and “since the Guam was available with aircraft which were suitable for a fly-by, we decided to accept the Kenyan invitation.”

And if a knowledgeable journalist asked how USS Guam, which was normally stationed in the Mediterranean, was “available” the spokesman would dodge the question by saying that only Pentagon could answer that question with a rider that “I am not sure it is their usual policy to comment on ship locations.”

There was the fear that if the USS Guam visit was simultaneously announced by Nairobi and Washington, the degree of attention could increase and that could lead to “misinterpretation” – which was Kenya’s concern.

On December 14, Marshall reported back: “President Kenyatta was obviously pleased with fly-past, but did not mention it in his speech.” He also reported that the Kenya Army Commander, Maj General Jackson Mulinge and Air Force Commander Col Dedan Gichuru went to Eastleigh after the festivities – and skipped the garden party. Civilians who lived within the

Eastleigh Air base were allowed to walk by the helicopters and the jets.

On the same day, Kiereini spoke with the US Deputy Chief of Mission, Ralph Lindstrom and it was reported that he was “ecstatic” over success of fly-by.

“He said that President Kenyatta had been very impressed and that Attorney General Njonjo remarked immediately after fly-by that it was a pity there were no more planes,” Marshall reported.

According to Kiereini, the low-key manner in which press announcements had been made probably accounts in part for the absence of public reaction by Somalia and Uganda, “who nevertheless undoubtedly got message that Kenya has a friend.”

While Kenya had shown Idi Amin – who was receiving Soviet support – that it had support from Washington, the US ambassador described the mission as “an excellent example of how US military power can be discreetly used to support US foreign policy objectives.”

jkamau@ke.nationmedia.com @johnkamau1

Credit: Source link