Ahmed Ismail Hussein Hudeidi, a founding father of modern Somali music, died in London after contracting coronavirus at the age of 91. The BBC’s Mary Harper was a friend of his.

Whenever Hudeidi played his oud, it was impossible to keep still.

Bodies swayed, hands clapped and fingers snapped. His music was transporting and somehow possessed your whole being.

But there was even more to Hudeidi, or the “king of oud” as he was popularly known, than his sublime music.

He was a life force; warm, generous, humble and funny.

Bus driver as student

From the moment I met him, I felt I was part of his family.

I was not the only one. He welcomed everybody to his London home, preparing strong Yemeni coffee and offering a bed to anyone who needed it.

It was an informal music school, with people coming from all over the world to learn from the maestro.

One student was a Somali woman in her 60s who had never before been allowed to learn music. Another was a bus driver.

Whenever I saw the police band playing drums I would run after them, imagining I was beating those instruments. I would get carried away

Hudeidi was born in the Somali port city of Berbera in 1928. He grew up across the Gulf of Aden in Yemen and was attracted to music from a young age.

“Whenever I saw the police band playing drums, I would run after them, imagining I was beating those instruments. I would get carried away, losing the sense of time, until a member of the family would find me and take me home,” he once said.

When Hudeidi was 14 years old, his father took him to a party in Aden. An oud was being played and Hudeidi fell in love.

He described his affection for the rounded wooden instrument as an illness; whenever he saw one, he just had to pick it up and play.

What is an oud?

- Stringed instrument often described as similar to the European lute

- Its history stretches back thousands of years

- Central to a lot of Arab music

- Made of wood typically with 11 strings, five are paired together

Source: ArabAmerica.com, Salon Joussour

It was around this time that Hudeidi met the legendary Somali composer and oud player, Abdullahi Qarshe.

“One day I began to touch and caress his oud. Qarshe noticed this immediately and asked me what kind of things my father bought me to take to school.

“I said: ‘Books and pencils’. Qarshe said that was fine but that he should also buy me a basic oud.”

‘Devil’s work’

Hudeidi learned quickly and shone as a player, winning prizes at carnivals and making a name for himself. He moved back to Somaliland, then on to Djibouti where he was booted out by the French colonisers for singing political songs.

He went back home, where he also got in trouble with the authorities. At one time they tried to ban his music, describing it as the “devil’s work”.

The musician once wrote a letter to the head of the National Security Service asking: “Where is that large vessel brimming with fresh milk and the lush grass they had promised?”

He said this angered the man, who “sent a stern word to me to the effect that if I did not stop such mischief, they would see to it that my high reputation among Somalis would be ruined”.

His popularity made other performers jealous. He described how some envious musicians poured ghee into his oud, which led him to compose the verse:

If I am not precious to you, Oh Ms Nothing

And your succour is no more, I, too, have given up on you

Hudeidi eventually settled in London but travelled all over the world, delighting people with his musical mastery. Age was no issue. He was still playing concerts in his 90s.

Despite his exalted status, the ‘king of oud’ never liked making a fuss.

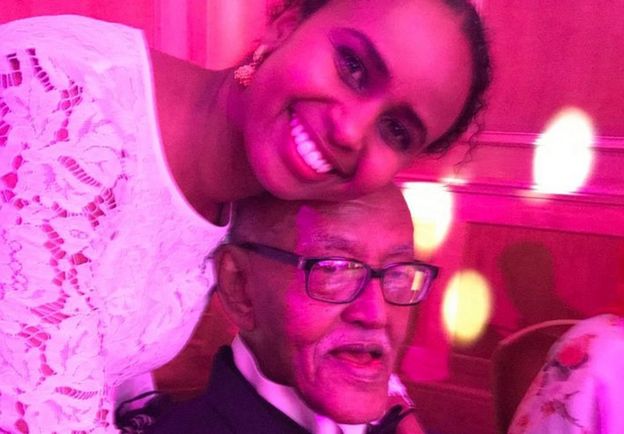

I remember a prize-giving ceremony in London where he was being presented with a lifetime achievement award. It was a black-tie event and Hudeidi’s niece brought a bow tie for him to wear, but he was having none of it.

In the end, we had an amusing tussle with him as we tried to persuade him to wear it, at least for going up to the podium.

He also had a cross-generational appeal.

‘The best father’

I went to one of his concerts in the basement of a small bookshop in London.

Somehow, the famous young Somali musician Aar Maanta got wind he was playing there. He rushed from home with his oud, ran down the stairs to the crowded room, grabbed a chair and started playing with Hudeidi, both men grinning and laughing as they worked their magic.

Sultan Ali Shire is Hudeidi’s official biographer. He was also a long-time student of his and describes Hudeidi as “the man who sowed the seeds of Somali music as it is today and the best father anyone could have”.

He started off as a teacher of music, but taught me history, culture and language too. Music poured out of him

Another of his students – and one who sometimes played in public with him – is author Nadifa Mohamed, who was like a daughter to Hudeidi.

“He was everything to me,” she says. “He started off as a teacher of music, but taught me history, culture and language too. Music poured out of him; even in his kitchen he would start drumming his fingers on the worktops.”

‘High-octane performances’

Hudeidi said it was not always possible to separate music from politics, especially during times of hardship, like the dictatorship of long-serving former President Siad Barre, or the long years of conflict, drought and other difficulties.

“He was a patriot with grounded civic principles,” says the US-based Somali professor Ahmed Samatar. “An artistic pioneer with bottomless stamina. He gave us over 70 years of high-octane performances.”

Mohamed says Hudeidi was “always a rebel, supporting people’s right to be individuals”.

This spirit did not sit well with everybody, including his parents, who were never happy with his musical career, right from the time he was a child.

“We were at war with each other,” said Hudeidi. “Kick and punch became the medium of our encounters. It was as if their boy had decided to destroy his life before it even bloomed.”

Many of Hudeidi’s songs have become part of Somalis’ DNA, no matter where they come from, no matter which clan they belong to.

His favourite song was one he wrote for his brother, Uur Hooyo or Mother’s Womb:

You, the abundant light

That my eyes graze on

Do not take me lightly

You who shared

My mother’s womb

He saw music and his teaching as a way of trying to maintain cultural continuity despite the divisions caused by 30 years of conflict.

“The hearts of Somali musicians are heavy with sorrow that comes from our broken common history and thus the loss of our rich cultural heritage,” he said.

He also saw music as a way of making sense of things.

“The artistic imagination not only sharpens our view of the world. It also presents us with ways of understanding, speaking about, dreaming about and conducting our lives.”

Credit: Source link