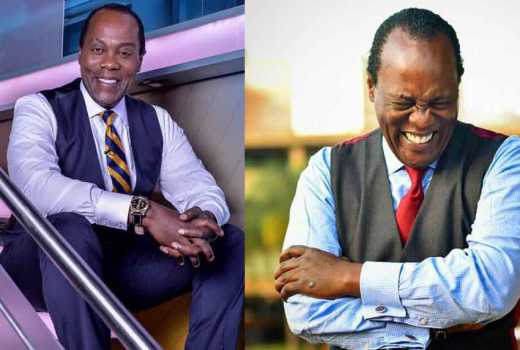

Jeff Koinange and I meet at Hurlingham’s Best Western Hotel, (now Four Points By Sheraton). Jeff has, in person, as much of a presence about him as he does on TV.

The air around him makes almost everything come to a standstill, and it’s not just about the fame and popularity, the effect has something to do with his individuality. It’s the kind of effect that makes heads turn.

Jeff steps out of his very swanky car crisply dressed, with sunglasses on, and, before he can even get to the hotel’s main entrance from the parking lot, passersby start waving at him. He warmly acknowledges all of them, it’s an interesting sight to see, this, his humility.

As we walk into the elevator, and up the stairs to the Ciroc Bar, Jeff attempts to tell me about his day, but, this proves almost impossible, since his phone won’t stop ringing.

Jeff has worked as a reporter and correspondent for international TV networks such as Reuters and CNN. Now in Kenya, he remains well-known as the journalist who asks his guests tough questions, on what is belovedly referred to by his Kenyan fans and followers as, “The Bench.”

While he is as exuberant and inviting and engaging as his TV persona depicts, there’s a side to him that would be largely unbeknownst to the public, Jeff is extremely serious when it comes to professionalism. He does not faff around with work.

When we both finally settle down to start the interview, he says, “You have one take Yvonne, you have to get it all right, the first time. Understood?”

It’s a stern instruction, and a slightly intimidating one, given that Jeff is such a pro journalist.

However, as we start and get into it, Jeff warms up quickly. He has a witty sense of humour, comebacks that one would ordinarily not expect and, in response to some of my questions, he in turn whips up queries that catch me quite off-guard, and then, we laugh at it all.

“Jeff Koinange,” how hard has it been to make a brand of that name?

Oh wow. Hard enough. Making a name, or making a brand, takes time and lots of effort. So when people appreciate it, that’s great, it’s well and good, but not everybody does.

No? Not even for you Jeff?

(Laughs) Oh gosh, no. I’ve had my fair share of naysayers. But it comes with the territory, so it’s all good.

How do you deal with haters?

Look, not everybody will like you, and that’s okay. That’s totally fine.

I’m of the opinion that, if there are haters, where there are haters, they fuel you, they make you work even harder to try and convince them. This is okay with me, it’s fine.

“Through My African Eyes,” is the latest book you penned, will you work on another book?

Never say never. Dr. Myles Munroe, before he passed away in that horrific accident, said I should work on 10 books, so I have 8 more to go.

There probably is one down the line, but we’ll see. This one alone, took me seven years to write, so, there’s no rush to write another one.

Writing can be quite a process; in the times when you were really struggling with the contents of the book, how did you get your mojo back? How did you pull through?

Writing is indeed, such a process. I stepped away during such times.

I would just put the manuscript away, walk away from it, and not come back for a week, a month, six months. I would do that, because sometimes, you can’t push it, you know?

You know when you get that drive back, and when it’s time to get back on the computer, and start typing away. And when the spirit flows, you have to take advantage and fully maximise on it. But it’s not something that should ever be forced, no.

What have you seen, through your African eyes?

Well look, if I tell you now, you’re not going to read the book, are you? (Laughs heartily)

For those who haven’t read the book yet, and are hoping to, what should they look forward to?

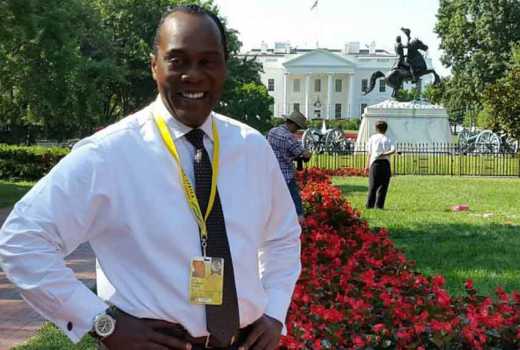

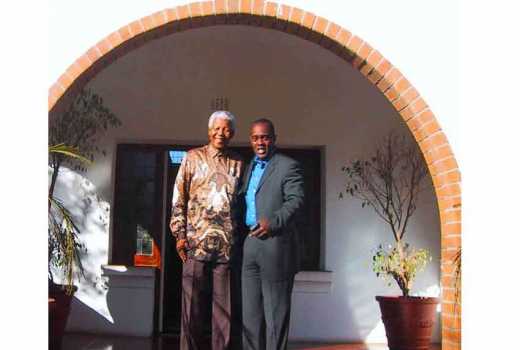

I’ve been to 47 of the 54 African countries, and covered them, in my time as I worked for Reuters Television and CNN, so I’ve had a front row seat to history unfolding in the last two decades.

Who do you want to read your book? Any particular target audience?

Anyone from the age of 8 to 88, that’s my span.

An eight year old child would be able to read the book because it’s so simply and wonderfully written, and I’m not just saying that because I wrote it, no, it truly is well written. Also, the key target audience is certainly Africans, that’s the main audience.

The kind of journalism you’ve practised over the years has had quite a lot of depth; you must have really seen the good, the bad, and the ugly of humanity. Have these experiences changed you in any way? Did they affect you?

They did, and what I’ve gained with all these experiences, is the appreciation of who I am as a person and where I come from, as an African.

For the longest time, our stories were told by others, but now, we can write and tell our own stories, and just the ability to be able to do that is incredible.

A lot of people would have ideas about who Jeff is, perhaps put you on a pedestal, assume you never make mistakes, or never go broke, actually, do you go broke Jeff?

(Shakes head) Pfft! Could you lend me some money? (Laughs)

Err…how much are we talking here?

(Breaks out in laughter again) Yeah, exactly. And look, that’s what people think, it’s the stereotypical image they have of me, and I hope I can set the record straight with the book, because, everyone thinks I grew up privileged.

I do go broke, just like the next person. But because I was born into a family name like this, ‘Koinange,’ they say, “Oh, you people have a street named after you, your people were in government for the last 50 years.”

And for me it’s like, you know what, that’s all well and good, but listen to my story, listen to the fact that my father died the day I turned two months old, leaving a 28 year old widow to care for four kids on her own, and she did. You know, read the story, don’t just imagine.

Is this why people are misunderstood, assumptions?

This is exactly why people are so misunderstood. And it is also why I think it’s important for everyone to write their story, because, people assume whatever they want to assume.

Even then, at the end of the day, I might not be able to convince some people. They’ll still sit and think, this is just a book, it’s just a story. And that’s unfortunate.

Nothing.

Nothing?

Nothing. I don’t regret anything. I’m glad he wasn’t there in a way.

How so?

Because if he had died much later when we were growing up, that would have been very sad.

Also because if he was around, we might have ended up as some really spoilt brats as kids, and I’m glad we didn’t end up that way. So, you know, it’s not my calling, but, I think it’s a good thing he went.

Jamal, your son, how is it being a father to him?

It’s the most incredible thing. We really tried to have him, and when we finally did, we said we’d do our best to give him everything we never had, including the both of us, a father and a mother, which I particularly never had.

You and Shaila, your wife, tried real hard to have a child, and finally had Jamal through IVF; do you think the African society has come of age when it comes to the different kinds of solutions available for having children? Are we there yet?

We are. We are way past there. People are now openly discussing adoption and going out of their way to make it happen.

We are no longer just seeing wazungus on the streets with a little black kid, we are adopting our own, so yes, absolutely, we’re there.

If, God-forbid, you pass away in the next 10 or so years, what’s the one thing you’d like Jamal to always know?

I’d like him to know that he can be whatever he wants to be in this world. He has the opportunity, he has the background, he’s got great parents, (pauses), he can be whatever he wants to be.

So, if he wakes up one day and says, “I want to become a carpenter.” What’s your response going to be?

“What kind of wood are you going to use?”

Ah, what an answer!

(Smiles broadly and nods).

In Kenya, we still hear the same narrative when it comes to creative works, that talents can’t really make money without having side hustles, why do you think this is?

I think it’s people’s attitudes. You can make money with whatever you do, you can make money selling newspapers on the streets. You can make money selling books. Look, if you don’t believe you can do something, then you won’t do it. If you believe you can do it…!

I mean, who ever thought the likes of Kipchoge Keino, going on down, that one day, they’d be multimillionaires? And that’s running only, you talk about us, and what we do? This, this is a different kettle of fish. You can make a hell of a lot of money, if that’s your intention, you can.

So, no need to fly abroad for opportunities?

No. The playing field has been levelled now, we are a global village. Gone are the days where one had to travel to America, or Europe, or Asia to make money, no. If you’re determined to do it, you’ll make it happen.

I don’t know, you tell me, you’re the famous one.

What? Wait, what?

(Laughs heartily)

(Looks down with a serious pause) I always tell people, fame is fleeting. And, be careful what you wish for, because you may just get it.

Those who wish for fame, and want to be on the cover of magazines at the end of the month, or in newspapers, or spotted at such and such a place, that’s the lifestyle you want? Go for it! But you have to maintain it. You have to live it up, every single day. It’s a lifestyle that needs lots of maintenance.

Do you wish you could get a break sometimes? Like, just take a break from being, “Jeff Koinange the famous journalist?”

I do, and I do take breaks. And I go somewhere where nobody will see me, or know me, I switch off my phone, and I just renew and refuel my energy.

Where do you go?

I won’t tell you. I can’t tell you that.

Right. Of course. I’ll write it down for you. (Laughs)

For the 20-somethings out there, who want to be like you when they grow up, who want to get into journalism and be famous, but right now they’re going through a quarter-life crisis, they don’t know what careers to get into, or what to do with themselves, what would you tell them?

Good, very good question. Two things, for someone who wants to get into my industry. One: you’re only as good as your last story.

You can write, you can edit, put together, report on, the most fantastic story seen on the planet earth. Everyone will be raving, talking about it, tweeting, Facebook-ing, trending, you’ll be the flavour of, literally, the day.

However, the human attention span is so short, that by tomorrow, everyone will have woken up and moved on. So, always remember, you’re only as good as your last story.

Right.

Two: no story is worth dying for. And this is certainly from experience.

There’s a story I talk about in the book about my time in the Niger Delta. It was a very controversial story concerning some rebels; that story could have easily gotten us killed.

Our death would have made breaking news that day, and maybe that evening too, but that would have been it, the next day, we’d be dead and forgotten. So no, no story is worth dying for, none whatsoever.

What’s the one main lesson you’ve learnt, from all your life experiences?

A key lesson of mine has been to live each day as if it were my last. To enjoy every day to the max.

We live in one of the most incredible countries in the world, good weather, great people, and even greater wildlife. Having travelled as much as I’ve travelled, I can say this without fear of contradiction, Kenya is a spectacular country.

And to anyone who wants to travel elsewhere, go, please go, but I can assure you, you’ll come back.

And, what’s the one lesson you’ve learnt about women?

Respect! My mother, again, young widow, she didn’t remarry, she was committed to educating her children, and she’s still alive, she’s over 70 years old now. That’s respect right there.

And every time I interview women on my show (shakes head), I realise it’s long overdue that Africans gave women the mantle. It should have been done a long time ago. If women were to run this continent, oh, I tell you, it would be, “Smoking!” (Laughs heartily)

Speaking of, “Smoking,” how does it feel to be on the other side of, “The Bench?” To be the one answering the questions?

Great, great actually. Less pressure. This is nice. (Laughs again)

Yvonne Aoll is a writer and freelance journalist.

Credit: Source link