In April 1997, Wired magazine published a feature with the grand and regrettable title “Birth of a Digital Nation.” It was a good time to make sweeping, sunny pronouncements about the future of the United States and technology. The US stood alone astride the globe. Its stock market was booming. Microsoft was about to become the world’s most valuable company, a first for a tech firm. A computer built by IBM was about to beat the world chess champion at his own game.

And yet, the journalist Jon Katz argued, the country was on the verge of something even greater than prosperity and progress — something that would change the course of world history. Led by the Digital Nation, “a new social class” of “young, educated, affluent” urbanites whose “business, social and cultural lives increasingly revolve around” the internet, a revolution was at hand, which would produce unprecedented levels of civic engagement and freedom.

The tools of this revolution were facts, with which the Digital Nation was obsessed, and with which they would destroy — or at least neuter — partisan politics, which were boring and suspicious.

“I saw … the formation of a new postpolitical philosophy,” Katz wrote. “This nascent ideology, fuzzy and difficult to define, suggests a blend of some of the best values rescued from the tired old dogmas — the humanism of liberalism, the economic opportunity of conservatism, plus a strong sense of personal responsibility and a passion for freedom.”

Comparing the coming changes to the Enlightenment, Katz lauded an “interactivity” that “could bring a new kind of community, new ways of holding political conversations” — “a media and political culture in which people could amass factual material, voice their perspectives, confront other points of view, and discuss issues in a rational way.” Such a sensible, iterative American public life contained, Katz wrote, “the … tantalizing … possibility that technology could fuse with politics to create a more civil society.”

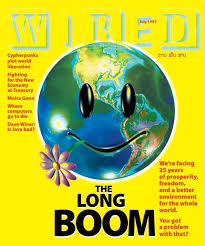

Such arguments, that a rational tech vanguard would spark an emancipatory cycle of national participation, were common at the time. (Though they were not unchallenged.) Katz’s is notable for its relative restraint. “The Long Boom,” an infamous piece published in Wired just three months later, predicted the spread of digital networks “to every corner of the planet” leading to “the great cross-fertilization of ideas, the ongoing, never-ending planetary conversation” that would culminate, by 2020, in “a civilization of civilizations” that would set foot on Mars in species-wide harmony. (Instead, we got Baby Yoda.)

This evangelism had a profound influence on the next 20 years of laissez-faire policy toward and positive public opinion about the digitization of American life. A deeply felt, mostly unexamined, sense that tech would lead to a freer and more convenient existence was the midwife of our digital present. It allowed the creator of a website to rate the attractiveness of Harvard’s women students to build an advertising platform with $55 billion in annual revenue. It allowed an online shop created to sell books to build a $25.7 billion cloud computing network. It allowed a company that started as a way for rich people to summon private drivers to turn itself into $47 billion, well, whatever the hell Uber is.

It hadn’t tamed politics. It sent them berserk.

Though challenged at the edges, this sense lingered. As late as 2012, even as the vast platforms that now control the internet had assumed their current shapes, the bestselling author Steven Johnson argued the glass was half full in his book Future Perfect — that “peer progressives,” enlightened digital natives, would end entrenched social and political problems through crowdsourcing.

Looking back from the shaky edge of a new decade, it’s clear that the past 10 years saw many Americans snap out of this dream, shaken awake by a brutal series of shocks and dislocations from the very changes that were supposed to “create a civilization of the Mind in Cyberspace.” When they opened their eyes, they did indeed see that the Digital Nation had been born. Only it hadn’t set them free. They were being ruled by it. It hadn’t tamed politics. It sent them berserk.

And it hadn’t brought people closer together.

It had alienated them.

The longest-running measure of alienation in American life is the Harris Poll’s Alienation Index, which has been calculated annually for more than 50 years. It’s a simple survey that asks whether respondents agree with these five statements:

What you think doesn’t count very much anymore.

The rich get richer and the poor get poorer.

Most people with power try to take advantage of people like yourself.

The people running the country don’t really care what happens to you.

You’re left out of things going on around you.

Harris then averages the rates of agreement to reach an index, which is a rough proxy for how included Americans feel in their country and their communities. In 1998, a year after the “Birth of a Digital Nation,” was published, the score was 56%. In 2008, as the platforms became dominant, it was 58%. Last year, it was 69%, the highest it’s ever been. (The lowest level, 29%, came in the Alienation Index’s first year, 1966, the same year HP began selling the 2116A — its first computer.) It’s easy to speculate about the reasons for this increase: a financial crisis that awakened Americans to the widening gaps between rich and poor; an opioid epidemic caused by corporate greed; entrenched racism and sexism; bitterly divided partisan politics; and, of course, technological change — the prism through which Americans view all of these things, and the vector that brings Americans’ feelings about all of these things together into the same few spaces.

I’ve spent six years reporting on deeply alienated people on the internet, during which time I’ve come to see conditions of disconnection and frustration everywhere the Digital Nation touches: on social media, in search algorithms, in the digital economy. In myself. The feelings of powerlessness, estrangement, loneliness, and anger created or exacerbated by the information age are so general it can be easy to think they are just a state of nature, like an ache that persists until you forget it’s there. But then sometimes it suddenly gets much worse.

There is no legal recourse — only participation in a public system that abuses its users.

Much worse: The Americans who marked this decade most visibly with their anger and impotence are, of course, young white men. In the summer of 2014, I first reported on the jilted 24-year-old who started an unlikely social movement with a seething blog post about the behavior of his ex-girlfriend, an obscure game developer. Gamergate! It was so stupid and about nothing and quickly became so scary and about everything. An entire culture of alienated posters and clever scammers cohered around it, around the impulse that something needed to be protected and some people needed to be attacked. What you think doesn’t count very much anymore. Some of these young men were trolls, others neo-Nazis. Some got TV shows. Some got paid out by billionaires. Some made it to the White House. Many wanted media careers. A few stewed for so long in their own resentment and the deeply sad world they created that they broke with reality. Several killed. One committed one of the most horrifying crimes of the 2010s.

Many more made threats, one of the defining features of life online in the 2010s. All things considered, we barely heard from the people who received them — a failure I was a part of. Try to imagine every woman and every nonwhite, non-Christian and LGBTQ human who has been threatened with death, torture, rape, or worse, on a major social platform. Add up all of those feelings of anger and powerlessness, against the backdrop of a $24 billion company that wouldn’t take it seriously for the longest time. There is no legal recourse — only participation in a public system that abuses its users. What you think doesn’t count very much anymore. People say: “Ignore it. No one dies from internet harassment.” Or else: “I’m so sorry for what you’re going through,” like it’s a divorce or a death in the family. Both are alienating, and I write from experience. Sometimes, for reporting, I received messages over Twitter and Facebook containing images of my father, who is dead, superimposed in a gas chamber. The joke is that he was Jewish.

The truth is we don’t have the right language yet to talk about an entirely new constellation of alarming and negative interactions, from threats to dogpiles to friend requests that go unanswered for a bit too long to yes, sorry, cancellations. They’re both more and less serious than we can manage to express with words, and the gap between that and what they feel like is an alienation.

What is an information Superfund site?

Experts might call the pictures of my father pollution in my information ecosystem. This is the best metaphor available as of 2019 for media that is bad for us. What, then, is a pristine information ecosystem? What is an information Superfund site? How do you do toxic information cleanup on, say, a town that has been poisoned by the internet? For that matter, how do we even agree on what’s toxic? Every attempt to name the problem with bad information on the internet runs into the “fake news” dilemma: Anyone can use this metaphor at scale, including and especially people who have a vested interest in keeping things extremely toxic. The sense that shared language is impossible: an alienation.

Even when we get “good” information online, we can’t always be sure where it’s coming from and why we’re seeing it when we’re seeing it. A profit-driven information apparatus uses a huge and growing fake user base to juice the statistics it shows to advertisers. The incentive is not to show you true things, but to be able to claim as many people as possible are seeing something, anything. To be no different to the men with the money than a bot, that’s an alienation. To not know where the things you read and see come from, nor that they’re real, that’s an alienation. To labor to pick out true from false, and know that many Americans don’t bother to do the same, that’s an alienation.

There are people who thrive in this world, of course: certain kinds of strivers, grifters, presidents. People who are very tendentious and very persistent. I reported a story this year about two young scammers who’d spent their whole lives online, honing their skills. They fabricated an entire world on social media with nothing more than time and used it to lead a young woman to her death. Were they the exception or the example? I couldn’t tell. Seeing people like this get their way over, and over, and over: That’s an alienation.

The big social media platforms are trying very hard to address the problem of toxic information, they tell us. But the algorithms that they tweak — I personally always imagine an old Swiss watchmaker squinting through a loupe — are top secret stuff. Secret corporate formulas encourage conspiratorial thinking. You’re left out of things going on around you.

Creators, who depend on these algorithms for money, are thus alienated, as are the people who consume their creations, which are frequently conspiratorial. And the creators are the (relatively) privileged ones! Each major social network is a brutal hierarchy. The people who ascend tend to be teeth-grindingly obsessed with what works and what doesn’t. The people who don’t suspect the risen have achieved their status through a series of inauthentic poses. Or they feel grossly inadequate. Either response is alienating. What you think doesn’t count very much anymore.

To be alienated from one’s labor — that rings a bell!

These dynamics play out in a desperate theater of social media optimization that my colleague Anne Helen Peterson so memorably described in her viral story about millennial burnout. It’s almost always unpaid work, the product of which doesn’t belong to the person who makes it. To be alienated from one’s labor — that rings a bell!

Which brings us to the new economy of freelancers and gig workers, precarious, unprotected, and connected. Hourly workers fry their brains with images no one should ever see — information detoxification — working to meet bizarre and inconsistent standards handed down from a distant authority, and then melt down in filthy bathrooms. Harried subcontracted delivery drivers feel so desperate to meet overnight shipping deadlines they get in deadly crashes. Uber drivers, some of whom sleep in parking lots, have separate bathrooms than Uber corporate staff. These people, it stands to reason, might be alienated. The rich get richer and the poor get poorer.

Meanwhile, the median home price is San Francisco is $1.4 million. This is where the Digital Nation mostly lives, in the most beautiful place in the country, profiting directly or indirectly off our participation in the alienating world they’ve built. Many of these people don’t want their children using the products and networks they build and sell. The people running the country don’t really care what happens to you.

Still, they’ll listen to you and spy on you for law enforcement. They’ll use that data, which they may or may not protect, to get richer. They’ll build special privacy schemes for themselves. Most people with power try to take advantage of people like yourself. Disempowered and unsure how to express it, you may take a strange comfort in the fact that there is another alienated human on the other end of your device. You’ll never meet them, but at least they will hear you.

Near the end of “Birth of a Digital Nation,” Jon Katz acknowledged that the new digital elite would have one natural division from the country they were bound to inherit: class.

“The digital world is often disconnected from many of the world’s problems by virtue of its members’ affluence and social standing.”

Membership in the digital nation as it exists today is a kind of class identity, of course. As Katz rightly predicted, its members’ “business, social and cultural lives increasingly revolve around” the internet. The luckiest of this group, high on meritocratic myths, have founded or found lucrative jobs with a handful of tech firms. The rest of us enrich them by using their platforms and their services. This is surely not the kind of participation Katz had in mind.

To his credit, Katz understood the harms that lead to alienation. “Alienation online — and perhaps offline as well — is not ingrained,” he wrote. “It comes from a reflexive assumption that powerful political and media institutions don’t care, won’t listen, and will not respond.” He just couldn’t conceive of a digital world that made them worse.

It seizes some of the best, noblest human instincts and harnesses them to a degrading system of profit.

Here is the most alienating fact about the Digital Nation we live in: It incentivizes forms of engagement that make Americans feel less empowered and more alone than ever, to the benefit of very few. It seizes some of the best, noblest human instincts — to share, to know, to connect, to belong — and harnesses them to a degrading system of profit. Anesthetization to these conditions is dangerous. Cynicism and powerlessness are the hallmarks of another form of digital life, an authoritarian one Americans should badly want to avoid.

I wonder, as the US stumbles into a new decade, what kind of groups and communities we’ll form to deal with these feelings of alienation. Alienated people are especially vulnerable to the destructive forms of belonging promised by nationalism and racism. We know where those lead. Among those who can afford it, people may simply pay their way into less alienating online experiences. One thing that gives me a small amount of hope is the recent wave of tech worker organizing. Whatever becomes of it, it’s heartening to witness a group of people who are part of this alienating system attempt to build a movement around solidarity and direct action.

Or maybe we’ll relearn, as the writer and artist Jenny Odell suggests, to do nothing, its own form of action. That’s an American tradition, too. ●

Credit: Source Link