Atop a bridge, a dry, sandy stretch welcomes you to Mwingi town. This is what remains of the Kivou River, where water has been replaced by heaps of sand and rowdy, idle young men who sit by the river banks chewing miraa (khat) and smoking bhang day and night.

The young men, in their hundreds, rule Kivou village, the settlement next to the river, with an iron fist. Residents cannot speak freely about the sand gangs without looking over their shoulders to see if the men are watching. They then lower their tone, whispering that if their identities are known, their lives would be in danger.

But if they do not speak out, their livelihoods and future generations are at risk.

Musyoka Musesi is a former chairman of the sand association. Speaking in a tough but assuring tone, he is unhappy that sand harvesting continues though it is outlawed by the county government.

“I will never want to be associated with sand harvesting. I was their chairman but last year I resigned because I was fed up when the issue of sand got politicized,” he said.

“In September 2021, I brought Governor Charity Ngilu to Kivou to inform the community that sand harvesting had been banned. However, the harvesting continues unabated.”

High places

Mr Musesi had done his best to protect the Kivou River, the environment and the livelihoods of thousands of Kivou residents who have depended on this river for many years.

“Right now, I do not care whether the goons scoop and carry all the grains of sand, they can even take the river with them. It is painful seeing such a resource going to waste yet you can do nothing about it because the perpetrators are protected by people in high places,” Mr Musesi shared.

With the uncontrolled scooping of sand, the water table in the area has gone down. Private boreholes have dried up, and even the water level in the county government-owned borehole is so low that it can hardly serve the community.

Women and children spend hours trekking in search of water for domestic use, sometimes covering over five kilometres.

“We have to wake up early before the scorching sun is up. It is easier to fetch water in the morning because there are not as many people but as the day progresses the queues become longer and the sun is unbearable,” said Rosebeth Kiala, a 27-year-old mother of two.

Her family’s borehole dried up in November last year. She has tried to talk to the young men to abandon the illegal sand harvesting but this has fallen on deaf ears.

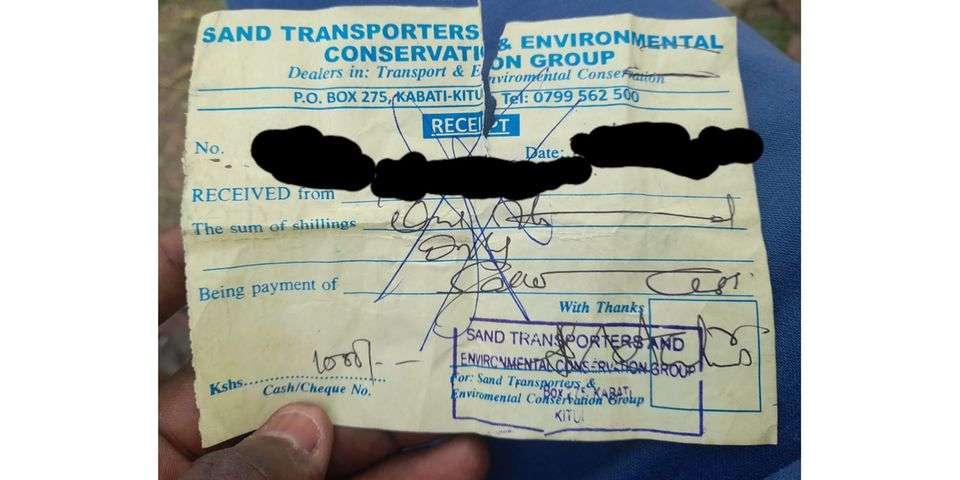

“Because of the allure of the quick money, most of them did not proceed to secondary school. They work in groups and the sand brokers pay them Sh100 each for every lorry of sand that they fill,” she said.

“So, if their group fills five or more lorries a day, each earns over Sh500. But they use the money to buy bhang, miraa and cheap liquor.”

It is this money that has sustained the mushrooming of food kiosks along the banks of the Kivou River, with women busy cooking food – mainly ugali and beans stew, githeri and tea. They also sell miraa, bhang and cigarettes to sand harvesters.

The illegal and uncontrolled sand harvesting has negative environmental and social effects on the community and the youth and has a gender dimension, said Rachel Kasyoka, a resident of Kivou village.

There is looming danger: unusual flooding is likely if the uncontrolled sand harvesting continues without the Kivou River being reclaimed by building gabions near the Enziu River, Ms Kasyoka said.

Already, with the dropping water table, residents struggle looking for water for domestic use and for their farm animals. Not only this, but farms around the river bank have dried up.

“We no longer do any farming as there is no water, and rainfall in our arid area is erratic. We used to grow vegetables to sell and for subsistence use. I have three plots along the river but I cannot farm as they have all dried up and one of them is being used in illegal sand harvesting,” said Ms Kasyoka.

“If the April rains fail, the drought and famine situation in our area will be bad by December. It is time that the county government and the local administration took action,” Mr Musesi observed.

Residents have petitioned the county government to act on the illegal sand harvesting at the Kivou River and reclaim the river, whose waters have dried up and the bridge on the river is cracking. “But our plea has fallen on deaf ears. This bridge was repaired just a month ago and it is cracking for the third time now,” Ms Kasyoka said.

Kivou village

Kivou village sits next to Mwingi town, off the Mwingi-Garissa road. The weather is hot and dry, the vegetation is characterised by dispersed thorny shrubs and the soils are sandy. The area is hilly and rocky, and whenever it rains, the water deposits heaps of sand in the riverbeds. It is this sand that has brought a huge environmental, socio-economic and security problem in the village.

Along the Mwingi-Garissa road lorries can be spotted transporting sand towards Thika town. This is testimony that sand is a huge economic activity in Mwingi. Sand merchants have established themselves on roadsides, with heaps of sand being sold in strategic places.

However, locals have not achieved economic emancipation. While some of them have invested in constructing shopping centres along the Thika-Garissa road, most of the buildings – old and new – are wasting away as they remain closed with no economic activity.

Only the Matuu-Thika junction remains busy with restaurants, bars, fast-food kiosks and fruit vendors making a killing from travellers.

Most of the farms in Mwingi have dried up, and livestock keeping – mainly cattle, goats, sheep, and donkeys for labour – is the main farming activity. This is unlike how things were five years back, when the Kivou River used to feed many families.

Residents used to farm vegetables such as tomatoes, onions, spinach, kales and pumpkins, cereals such as maize, and beans, cowpeas, green grams and others. This harvest is what sustained most of the agribusinesses in Mwingi township and locals benefited greatly from providing labour on farms.

Today, the river does not even have any water for their animals, let alone for domestic use. Farming along the river banks and irrigation agriculture are far-fetched dreams for locals. This has fuelled rural-urban migration as locals leave in search of livelihoods in urban areas across the country.

The diminishing unproductivity has also seen land values depreciate. Soil merchants have pitched tent along the Mwingi-Garissa road, taking advantage of the vast swathes of unproductive land as the area receives minimal rainfall.

An acre of land in Matuu and Mwingi sells for between Sh2 million and Sh5 million, which in the near future may have a socio-economic implication for locals.

With uncontrolled sand harvesting, the river has dried up, leaving behind swathes of acacia trees and cactus.

Credit: Source link