It’s almost Christmas, so let’s have some fun. Welcome to our first mailbag! This is gonna work much like it does for my colleague Kevin Pelton, who covers the NBA for ESPN. You can send me questions on Twitter (@rwohan) or via email to ohanlonmailbag@gmail.com, and then I’ll answer them in these periodic mailbag posts throughout the year. As long as your question is at least tangentially related to the sport of soccer, it’s fair game.

Let’s get to it.

My first thought for a question was ‘Is Trent Alexander-Arnold the best right-back in the world,’ but I’m not sure that’s the best way to frame it, considering he does things differently from someone like Joao Cancelo or Reece James, and maybe it’s an apples-to-oranges comparison. So my question is this: let’s assume you have been hired to build the best football team on the planet. Money is no object, every team will sell their players to you and every player wants to play for you. Is Trent your choice at right-back?” — Mauricio

The short answer: yes. Now for the long answer …

To my mind, TAA is the best attacking right back since Dani Alves and, well, he might be even better.

Alves was a secondary creator on the great Barca teams that also had Lionel Messi, Xavi, and Andres Iniesta — perhaps the three most effective creative players of the 21st century. TAA, meanwhile, is Liverpool‘s most important player in progressing the ball up the field, moving the ball into the penalty area and creating chances for his teammates.

It’s one thing to do that for, say, a midtable side; someone like Eintracht Frankfurt‘s Filip Kostic comes to mind. All of Frankfurt’s buildup and creation comes through him, and it sure seems like there’s a ceiling on what a team like that can look like. Well, Alexander-Arnold has been doing that for one of the three or four best teams in the world for nearly half a decade now, and I really don’t think we’ve fully appreciated how special of a player he is. The guy wasn’t born until after the 1998 World Cup!

According to the site FBref, TAA ranks in the 99th percentile for fullbacks in expected assists, shot-creating actions — defined as the “two offensive actions directly leading to a shot, such as passes, dribbles and drawing fouls” — and progressive passes. Everything you want a full-back to do in possession, he does better than everyone else. But as Mauricio points out, fullback-to-fullback isn’t even really the right statistical comp for Alexander-Arnold. No, he needs to be compared to all creative players — and even there, he’s still without peer.

In the Premier League this season, he leads everyone in progressive passes, shot-creating actions, passes into the penalty area and expected assists. Stretch it out to all of Europe, and only Thomas Muller bests him on xA, while only Dimitri Payet has more shot-creating actions. TAA leads the way in progressive passes and passes into the penalty area.

I cannot stress this enough, so I’ll say: THIS IS UNBELIEVABLE.

Lionel Messi and Neymar are the only players that have consistently done all of these things at this level over the past decade, and Trent is a freaking full-back. You get all of that good stuff while still being allowed to play the same number of attackers and midfielders as everyone else. He’s a cheat code.

Oh, and guess what? He might have added goals to his game, too. He’s taking more shots than he ever has before (1.78 per 90 minutes), and they’ve inched closer to the goal (21.6 yards away, compared to a career average of 23.1). As such, his expected-goal rate has jumped up from 0.08 per 90 to 0.12. He’s pretty clearly still getting better.

So yes, were I given unlimited money, I would immediately acquire perhaps the greatest creative player in world soccer. Liverpool do not have unlimited money, and they’ve still been able to be one of the best teams in the world by building everything in their build-up play around their right-back.

Now, is he the greatest 1-on-1 defender in the world? No, but in this thought experiment we’d be able to afford the kinds of players that can cover up his weaknesses, and I also think his defensive short-comings are a bit overblown. Most of his “bad” defensive moments come from teams exploiting the space behind him as he’s doing all the things we’ve already talked about, but that’s often not his fault. Jurgen Klopp wants him to be pushed up the field as high as he can go.

The way I see it, TAA is already one of the 10 or so best players in the world, and you figure out how to get players like that on the field. With our hypothetical team, funded by a shadow trillionaire who presumably controls most of the world’s major natural resources, we’d be planning on dominating possession and not putting Alexander-Arnold into too many situations where he’s defending deep in his own half. In other words, we’d be trying to play like Liverpool.

But even if we were a less talented team than that, we’d still build our whole team around TAA because, by definition of being “less talented,” TAA would likely be our most talented player. I think maybe a couple years ago, there was a reasonable argument that outside of the specifics of the system at Anfield, you’d want other players in the right-back slot because of Alexander-Arnold’s defensive deficiencies. But now he’s just straight up an absolutely world-class creator who demands to be on the field, no matter who else is on your roster.

What is the most notable player skill that doesn’t actually help teams win? And vice versa, what is the least notable player skill that helps teams win? Notable, as in easily analyzed or frequently commented on by announcers and analysts. — Zach

I love this question, and I think my answers are somewhat interrelated. The most notable skill that doesn’t actually help teams win: dribbling. The least notable skill that actually helps teams win: off-ball movement.

The reasons for the misconceptions are pretty intuitive. Dribbling looks awesome! Who among us has not passed out from sheer joy at watching Adama Traore barrel through an entire team without losing the ball? If you took someone who’d never watched soccer before and plopped them in front of a TV on a Saturday morning, they’d almost definitely point out the players who run past defenders with the ball at their feet as the ones they thought were “best.” Why? Because they drive the crowd and the announcers wild.

Now, not to be all “the ball moves faster than the man” here, but well, the ball moves faster than the man, man.

Every time you see a player sizing up a defender for a 1-on-1, the shifting dynamics of the match cease to exist, and the rest of the defense can position themselves in orientation to the duel that’s about to occur. You can’t really dribble past a player with your head up, so every dribble sort of temporarily eliminates all of a player’s teammates from affecting the play. By comparison, a player opting to pass can make 10 different individual decisions — all of which have to be accounted for in some fashion by the defense.

This isn’t to say that dribbling isn’t a valuable trait when executed successfully, just that its aesthetic appeal doesn’t quite match with its effectiveness. Even a successful dribble is happening at the expense of more dynamic and likely more dangerous ball movement.

Statistically, there’s some evidence, too. The analyst Mike Imburgio created a model called DAVIES that both classifies players into playing styles based on what they do most often on the field, and then values all of the on-ball actions a player takes. What he’s found is that the average player creates more value in build-up play and by getting touches in the box than by dribbling past players. The model itself also proved to be more accurate by giving more weight to progressive passes than progressive carries, and among the three styles of attackers, “finishers” and “playmakers” are on average more valuable than “dribblers.”

As for off-ball movement, we can’t really put any data on it yet — or maybe ever — but there has literally never been a good professional soccer player who didn’t know how to move off the ball. Unless you’re capable of dropping all the way back to your keeper, dribbling through the entire team and then slotting the ball past the opposing keeper, it’s pretty much impossible to positively affect a game without an ability, and an understanding, of how and when to move into different spaces.

Frankly, off-ball movement affects what happens in a match more than on-ball movement.

A writer who goes by the name “Tiotal Football” has been publishing a series that he calls a “Theory of Soccer,” in which he’s attempting to break the sport down into its component parts and understand the metaphysics of it all. It’s fantastic; do go check it out.

This passage in particular is relevant to our needs: “Too often, we like to think that soccer is about the decisions a player makes when he’s on the ball, based on the choices available. What’s most important is whether his teammates provide him these good choices to begin with (by being in the right place at the right time) and whether he does this in turn for them after he’s passed the ball. I suspect even a passer with poor technical ability can move the ball consistently to good places when his teammates are providing him multiple ‘good’ or ‘easy’ options through off-ball movement, and he himself understands how they’re doing this and reciprocates.”

In other words, a through ball from Kevin De Bruyne to Raheem Sterling only happens because 1) KDB recognized the space he needed to occupy to first receive the ball within, and 2) Sterling made the run that provided KDB with the option to then pass him the ball.

This is also the idea that buttresses the logic of expected goals (xG). Just listen to this interview with a young Gary Lineker, who talks about the importance of being “in the right place, all of the time” —

The best goalscorers score so many goals not because they’re so good at kicking the ball into the goal compared to their peers, but because they’re able to consistently find space in the penalty area that allows them to kick the ball at the goal, over and over and over again.

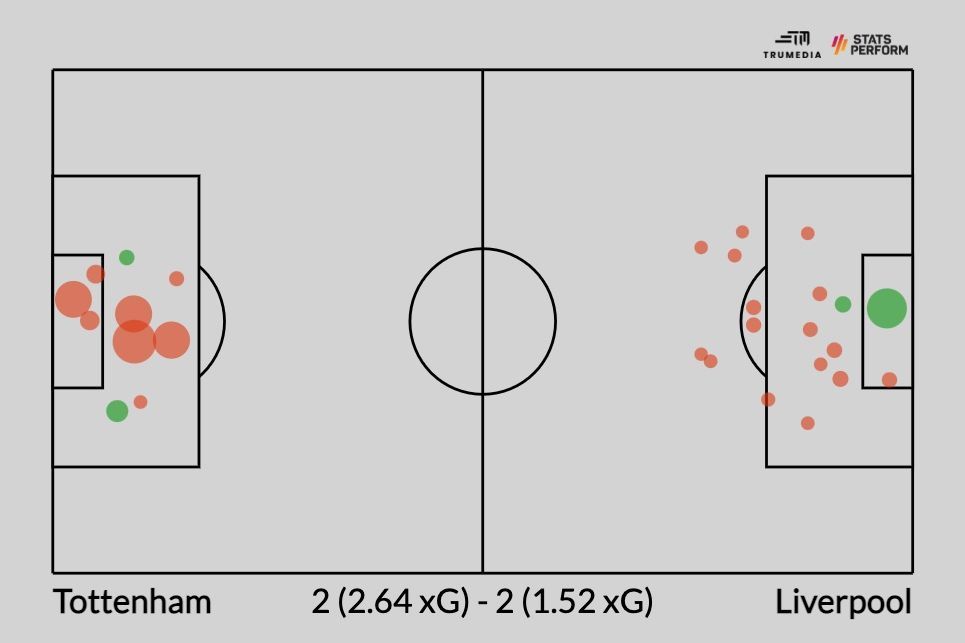

This weekend’s Tottenham-Liverpool 2-2 draw aside, it was quite clear that Antonio Conte has Tottenham playing much better than they have in some time. Obviously he’s only been in charge for seven matches, but do you think we can expect more improvements in the team? How many matches will Conte have to be in charge for before we have a sense of how good this Tottenham team really is? I recognize that there is likely a lot of confounding data and this may be a difficult question to answer. — Jacob

It’s only been five Premier League games, but early returns suggest they’re a hell of a lot better than they were under Nuno Espirito Santo.

- Goals per game: 0.9 under Nuno, 1.8 under Conte

- Goals allowed per game: 1.8 under Nuno, 0.6 under Conte

Small sample size and all that, but the underlying improvement has been there, too:

- xG per game: 1.1 under Nuno, 2.1 under Conte

- xGA per game: 1.7 under Nuno, 1.1 under Conte

Some advanced machine-learning techniques allow me to determine Tottenham’s per-game xG differential under Conte: exactly plus-1.0. Through 16 games, only Liverpool and Manchester City have posted better marks in the Premier League. Just five games in, Conte already has Spurs playing at a top-four level.

The more important question is: Does that mean anything? Lots of teams can play at a high level for a five-game stretch thanks to favorable schedules, the variability of human performance, refereeing hijinks and all that good stuff.

It certainly hasn’t been a tough start, fixture-wise, for Conte. The first four matches were against teams with an average table position of 16th. Then, the fifth match came against a Liverpool team ravaged by positive COVID tests, missing Virgil Van Dijk and their entire starting midfield of Fabinho, Thiago, and Jordan Henderson. Instead, Spurs got to play against 19-year-old Tyler Morton and 35-year-old James Milner. (Yes, they average out to a prime age of 27, but that is not how this works.)

However, you can only play against what’s in front of you, and they repeatedly ripped Liverpool to shreds. All the post-game talk concerning whether or not Harry Kane is in fact that kind of player and whether or not the VAR took a poorly timed early-evening nap during the first half distracted from just how well Spurs played. Given the balance of chances, they were really unlucky not to win the match.

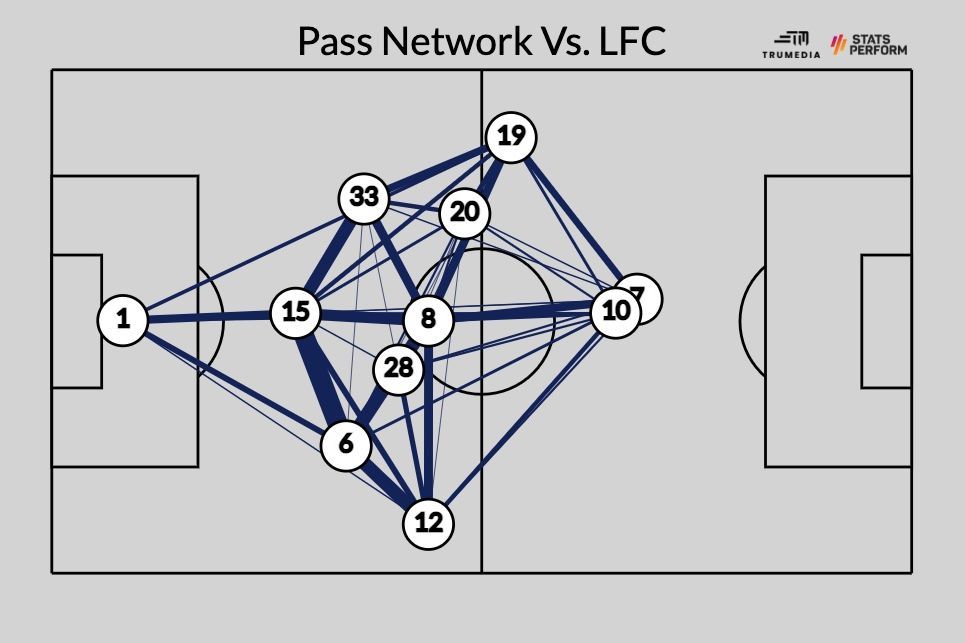

After the match, somewhat mockingly, Klopp said, “Tottenham set up a 5-3-2 and when they won the ball, they kicked it as far as possible, and Kane and Son were on their bikes. We had some struggles against this obviously.” He was right, both about how Spurs played and how effective it was.

Given all the postponed matches and unavailable players, it’s not super useful to look too deeply into any tactical trends or changes in playing time at Tottenham yet. But in the five games under Conte, the big difference in his Spurs compared to Nuno’s is how direct they’re playing. They’re moving the ball up-field at a rate of 1.45 meters/second — faster than the average Premier League team — while under Nuno, they moved at just 1.25 meters/second, slower than all but two other sides. That feels like something, especially since Spurs have mostly played against below-average teams who theoretically wouldn’t allow them to play at speed.

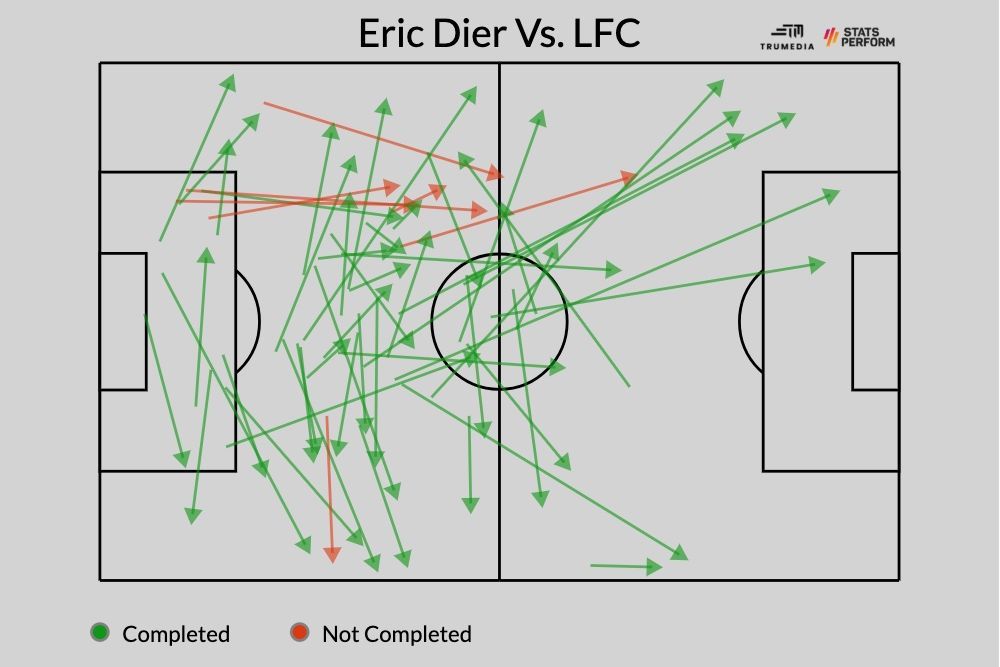

Specifically, it’s especially notable in how Eric Dier, the center center-back in the back three, is passing the ball:

He’s played pretty much the same number of passes per game under both managers, but he’s both playing (15% of all of his passes, up from 13%) and completing (61%, up from 48%) more long passes. While Dier’s career seemed to stall out in the post-Pochettino era, he’s always been able to play a nice diagonal ball. His new usage shows why Conte has been so successful in all of his past jobs: He only asks his players to do the things they’re good at.

If 10-man Atalanta played 11-man Atlanta United, who would be favored and by how much? — Michael

We need two things in order to do this: 1) a power-rating system that compares clubs across various leagues across the world, and 2) a numerical understanding of the value of a red card.

For number 1, we can thank our friends at FiveThirtyEight, who maintain a global power-rating system for 645 different teams in 40 different leagues. In those ratings, Atalanta sit at 19th, one spot below Manchester United and one above Benfica. Atlanta United are all the way down in 285th, one below Slovakian powerhouse Slovan Bratislava and one above midtable Austrian side Hartberg.

Of course, we need more than just rankings, and FiveThirtyEight gives each team an offensive and defensive rating, which signifies how many goals that team would be expected to score and concede against an average team at a neutral field. Atalanta’s offensive rating is 2.3 and its defensive rating is 0.8, while Atlanta United’s at 1.2 on offense and 1.4 on defense. Put another way, Atalanta would be expected to beat an average team by 1.5 goals, while Atlanta would be expected to lose by 0.2 goals. If we combine those two numbers, then Atalanta (plus-1.5) would be expected to beat Atlanta United (minus-0.2) on a neutral field by 1.7 goals.

But what about 10-man Atalanta against 11-man Atlanta?

A 2011 study by the analyst Mark Taylor found that over the course of a match a team will lose 1.45 goals by some combination of their declines at both ends of the field. So, if full-strength Atalanta were favored by 1.7 goals, then a 10-man Atalanta would still be favored, but by 0.25 goals.

Forget the biennial World Cup, FIFA. Can you please make this happen instead?

Credit: Source link