Here’s who Liverpool should hire to replace Klopp as coach.

Jurgen Klopp‘s eight years of managing Liverpool started with a massive lie. At his opening news conference in October 2015, he said: “I’m a totally normal guy.” He stuttered for a second then couldn’t resist: “I’m the normal one, maybe.”

Everyone in the room started laughing because they knew what he was referring to: Back in 2004, at Jose Mourinho’s opening news conference with Chelsea, Mourinho made sure to point out that he was not a normal guy. “Please don’t call me arrogant,” Mourinho said, “because what I’m saying is true. I’m a European champion. I’m not one of the bottle. I think I’m a special one.” Mourinho’s tenure at Chelsea was special. He backed it all up — and he only lasted at Stamford Bridge for three full seasons.

Klopp shocked the world on Friday by announcing that he’d be leaving Liverpool this spring, and with that, the Normal One will ultimately outlast the Special One by five seasons. Klopp has won every potential trophy he could and oversaw Liverpool’s rise from 10th place to top of the table. The last Liverpool manager to log as many games as Klopp was Bob Paisley, who won six league titles and three European Cups. Paisley stepped down in 1983 and died in 1996 at age 77.

Outside of Manchester City‘s Pep Guardiola, Klopp has no peers among his managerial contemporaries. He’s keeping the company of ghosts and men who stopped coaching a long time ago. A “normal” coach? Hardly.

In other words, Klopp is irreplaceable — but Liverpool still do have to replace him. So, how might they do it?

Why Liverpool (probably) won’t find another Klopp

Both Klopp and Guardiola came to the Premier League right as the definition of the modern manager was changing. Two years before Klopp joined Liverpool, Sir Alex Ferguson left Manchester United after 21 years. Three years after Klopp’s arrival, Arsene Wenger wrapped up his 22 years with Arsenal.

We knew we’d never see another Ferguson or Wenger. With the rapid globalization, monetization and professionalization of the Premier League, clubs went from relatively small concerns to massive business operations over the course of the Ferguson and Wenger eras. Ferguson essentially ran United: Every major decision that could possibly affect the first team ran through him. Wenger was thought so vital to Arsenal that the bank that financed the construction of the new Emirates Stadium required the club to guarantee Wenger would be employed for at least five more years as a precondition of giving the club a loan.

With the biggest clubs in England now global corporations worth billions of dollars, a coach would never again be so central to its operations as Wenger and Ferguson were. The rise of the sporting director and the growth of the American front office structure meant that a coach’s responsibilities would be to, well, coach.

The fixture list was rapidly expanding, meaning coaches were busy enough as it is, and the game itself was changing too. An increasingly fast-paced and physical sport meant that older players were being squeezed out. So, specific groups of players could only maintain elite performance for three or four years together, while the constant barrage of matches demanded an incredible amount of mental and emotional energy from the top managers. The best coaches, then, seemed most likely to mirror Mourinho’s model: three or four years, win as much as you can, then say goodbye as you burned out and your players lost their edge.

In particular, Klopp’s strategic approach — run until you can’t keep running, then keep running — should have a short shelf life. As should his man-management approach: living and dying with every touch and cultivating genuine emotional relationships with as many of his players as possible. Instead, it has lasted for eight-plus years — twice as long as any other ever-present Premier League manager outside of Guardiola, who has been with City for seven-plus seasons.

In the modern context, Klopp has been around forever. The average Premier League manager lasts for two years. In 2012, the average tenure was double that length. Eight years in 2023 is the equivalent of 16 years just a decade ago.

Within all the churn, there’s very little data to suggest that coaches influence a team’s results over the long run. As AC Milan co-owner Luke Bornn put it to me: “The vast majority of papers out there say coaches don’t matter. I’m oversimplifying, but that’s basically it.” Over the long run, almost every club performs to the level of its wage bill, which is just another way of saying, You’re only as good as your players.

Here’s the easiest way to look at it: There are basically two managers in the world who you could have a really high degree of confidence in improving your club’s performance for a significant period of time. They are Klopp and Guardiola.

With the latter, there’s no one better at maximizing a resource advantage. Even with all of the questions over the, you know, legality of Manchester City’s resources, we’ve also seen Guardiola produce dominant, outlier results at Barcelona and Bayern Munich before Man City.

Klopp, meanwhile, is simply the best at outperforming his resources at the highest level. There’s a reason the last team to win the Bundesliga other than Bayern Munich and the last team to win the Premier League other than Man City were both managed by Klopp.

Dortmund were never close to the richest team in Germany, but under Klopp, they won the Bundesliga twice and made the Champions League final once. Same goes for Liverpool in England, but they won the Premier League once, lost it by a single point twice, won the Champions League once and made the final two other times.

The data backs it up: There are “good” managers, and then there are managers like Klopp.

Here’s what Aurel Nazmiu, a senior data scientist at the consultancy Twenty First Group, said about Klopp: “Our research shows that in their first 12 months, a ‘good manager’ typically improves his/her team’s win probability by around 4.5%. In his first 12 months at Liverpool, Klopp improved Liverpool’s win probability by close to 10%. In other words, his performance impact was immediate and double that of a typical ‘good’ manager.”

Among teams rated at the level of an average Premier League team or higher, Klopp improved Liverpool by a higher degree in his first two years with the club than any other manager in the Twenty First Group dataset, which extends back to 2008. Just look at that line:

Klopp's impact at Liverpool has been enormous pic.twitter.com/w1XXCbdU9n

— Aurel Nazmiu (@AurelNz) January 26, 2024

The problem for Liverpool, then, is a pretty simple one: The best coach for Liverpool is the coach that just said he’s leaving Liverpool.

How could Liverpool replace Klopp, and who should they pick?

Now, it’s not impossible to replace Klopp. Liverpool knows this better than anyone.

In 1974, Bill Shankly suddenly retired after 700-plus games in charge of the club. This 2020 Guardian column about Shankly could just as easily have been written about Klopp yesterday:

[He] was always more than a great football manager. He was … a charismatic maverick whose utterances had an unexpected, undeniable poetry. Between his appointment as Liverpool manager … and his retirement … he transformed a second-rate club … into the finest team of its generation …. He led Liverpool like a revolutionary leader, casting his personnel not just as footballers but soldiers to his cause, and became a folk hero to the fans. At the same time he laid the foundations of the team that dominated the First Division and European competition for the decade that followed his retirement.

Shankly, of course, was replaced by Bob Paisley, who then led the club to even greater success. Klopp himself said that he only felt comfortable leaving Liverpool because he got the team “back on the rails.” The midfield has been totally rebuilt, and the side that finished fifth last season is back on top of the table.

The next Liverpool manager, then, doesn’t need to be the next Jurgen Klopp. The next Liverpool manager will be taking over a team that already is one of the best in the world — not the one Klopp inherited, which averaged a sixth-place finish in the six seasons before he showed up.

And while Klopp deserves all the credit he gets for Liverpool’s recent era of success, he is the first to admit that he couldn’t have done it without the players. And one of the big reasons that Liverpool have so many good players is that they had the most analytically advanced front office of any big club in the world.

Liverpool’s rise wouldn’t have been possible without Klopp, and it wouldn’t have been possible with the people who helped find the players who would fit best with Klopp. Famously, Klopp wanted to bring in Julian Brandt to play alongside Sadio Mané and Roberto Firmino, but sporting director Michael Edwards and the research department convinced him to take a chance on an Egyptian winger named Mohamed Salah. Imagine if that call went the other way?

While Edwards, his successor Julian Ward and head of research Ian Graham have all left the club over the past two years, the rest of the research department remains in place. After a year of wayward, coaching-driven recruitment, this summer’s midfield rebuild suggests the club has started to return to its more objective decision-making process. Interim sporting director Jorg Schmadtke will leave the club at the end of this month, and so Liverpool will need to replace him before they bring in their next manager.

While Klopp is a larger-than-life figure, Liverpool’s next coach doesn’t need to be that. In fact, he probably shouldn’t even be that. Instead, the next Liverpool manager likely needs to work within the more modernized structure that Liverpool used to great success while Edwards was still with the club: The data department identifies a list of targets for the position of need, then the coach and the sporting director pick between those options.

So, what does their next coach need to be? What makes Klopp and Liverpool’s data-driven approach work so well together is that Klopp wants to play wide-open soccer with lots of chances, and the nerds across all sports have found that coaches should be much more aggressive than they are on average.

“Jurgen is to be credited for it because he was willing to compromise on some players,” Graham told me last year. “And he liked good players. A lot of managers don’t have an eye for a good player.”

Xabi Alonso of Bayer Leverkusen, surprise leaders in the German Bundesliga, is currently the betting favorite for the job, and it’s a hire that would earn near-universal approval. Per that Twenty First Group metric mentioned earlier, Alonso has improved his squad over his first two seasons more than that of any coach other than Klopp and Diego Simeone at Atletico Madrid. (Eddie Howe, current Newcastle coach, and Roberto Mancini, who was fired by Manchester City in 2013, also rate above Alonso on the list — it ranks coaches going back to 2008 — but most of that improvement comes down to sovereign wealth funds buying their club and spending tons of money.)

The big hitch in this idea is the way Leverkusen plays. Liverpool have built a team of players who thrive in vertical chaos, pressing and pushing the ball up field, over and over again. Leverkusen, though, rank in the bottom 10 of all teams in Europe for the percentage of their passes that go forward and the speed at which they move the ball up the field. Klopp’s Liverpool also allow the fourth-fewest passes per defensive action (PPDA) with 9.2, while Alonso’s Leverkusen allow 13.2, which is below the Europe-wide average.

While Alonso could shift his approach to match Liverpool’s personnel or vice versa, we just haven’t seen either of those things happen yet. Given that, this is not as obvious of a hire as it might seem on the surface.

Per Twenty First Group’s similarity metrics, which compares coaches across the statistical outputs of their players at various positions, Alonso’s approach has a 63% match with Liverpool’s style over the past two years. Two of the most similar coaches — both over 90% — are Germany manager Julian Nagelsmann and Brighton’s Roberto De Zerbi. Nagelsmann, though, would have to leave a high-profile national team gig right before a major tournament (the Euros). Meanwhile, De Zerbi’s Brighton are even slower and less vertical than Alonso’s Leverkusen.

Instead, my mind keeps coming back to one name: Thomas Frank. He is currently coaching Brentford and, I’d argue, is a better fit than all the aforementioned options.

Uh, the dude coaching the team currently in 14th place?

Per Twenty First Group’s performance rating, Frank is the third-best coach outside of the England’s “Big Six” clubs in the Premier League, Spain’s big three in LaLiga, Bayern Munich and Paris Saint-Germain. In other words, he is one of the top candidates in the pool Liverpool will be selecting from.

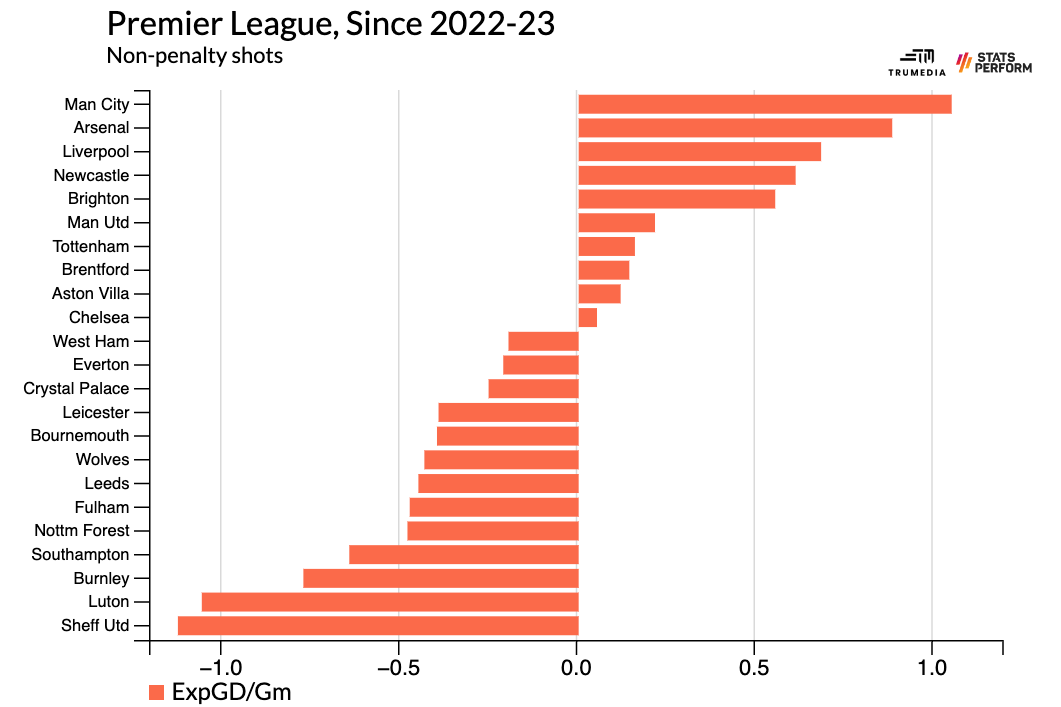

Why does Frank rate so highly? Here’s how the Premier League compares by non-penalty expected goal differential over the past two seasons:

Eighth best. So what?

Per the site FBref’s estimates, Brentford had the smallest wage bill in the Premier League last season. This season, only the three promoted teams have smaller payrolls. Plus, that relatively impressive underlying performance was often without their best player, Ivan Toney, who missed five games last season and has only played once this season, due to suspension.

Only Brighton rivals Brentford in terms of outperforming their resources, and Brighton rely much more on undervalued player identification than Brentford do. On top of that, Frank oversaw a significant stylistic shift in Brentford’s play as the team went from the Championship to the Premier League, and he is used to working within a data-fluent environment where the manager doesn’t have unlimited power.

Perhaps most importantly, Brentford aren’t totally dissimilar to Liverpool. Among all of the teams in Europe that move the ball upfield at 1.25 meters/second or faster and allow 11 passes per defensive action or fewer, only Barcelona and Liverpool have a better expected goals differential than Brentford do this season.

That’s not to say there’s no risk. Frank doesn’t have the same cachet among players that Klopp does, or that Alonso might. Plus the expectations of managing Liverpool aren’t the same as at Brentford. At Liverpool, you’re trying to win every game you play, while at Brentford, a draw is basically a win in nearly half of your games.

It’s just that every managerial option carries with it a good deal of risk. There is not another Klopp out there because there isn’t another Klopp. The only truly slam-dunk hire for Liverpool would be if they somehow convinced Guardiola to leave Man City, which isn’t going to happen.

Hiring Frank would not excite fans or the media in the same way that Alonso or Nagelsmann or even De Zerbi might, but based on how well Brentford have done with a relegation-level budget, I do think that in Frank, there’s a potentially great manager hiding in plain sight. After all, just hiring the normal one worked out pretty well last time, didn’t it?

Credit: Source link