Making headlines is never something that has motivated Kathy Sullivan.

Already in the history books as the first US woman to complete a spacewalk in 1984, the 68-year-old found herself in the news again this week after becoming the first woman to travel almost seven miles (11km) to reach the lowest known point in the ocean.

The two missions, total opposites in the minds of some, represent two extremes of a lifelong passion for Dr Sullivan: to understand the world around her as much as possible.

“I was always a pretty adventurous and curious child with interests wider and more varied than the stereotype of a little girl,” Sullivan told the BBC in a phone interview from the Pacific Ocean.

She was born in New Jersey in 1951 and spent her childhood in California. Her father was an aerospace engineer who, along with her mother, would always encourage their two children to think freely and join in with discussions.

“They really fed our curiosity on anything we were curious about or interested in,” she says. “They were our best allies to explore that interest further and see where it might take us: it might die out in a couple of days, it might be something that became our best hobby or it might turn into the central focus of our career.”

By the time they were five or six, it was already clear her brother wanted to grow up to fly aeroplanes. Sullivan, meanwhile, became fascinated by maps and learning more about the interesting places on them.

“Both of our careers have basically been remarkably wonderful fulfilments of those early dreams,” she reflects.

As a little girl, Sullivan was already devouring every newspaper, magazine and television report she could find on the subject of exploration. It was a time when Jacques Cousteau was making pioneering undersea discoveries and the Mercury Seven were propelling the image of astronauts into America’s mind.

“I saw these people – they happened to all be men, that didn’t bother me… I saw there are people in the world that have continually inquisitive, adventurous lives: they’re going to places no-one’s been and they have this store of knowledge and they’re learning more.”

“My way of thinking about it never crystallised into: I want that job, I want that title or that label,” she explains about her ambitions as a teenager. “But what I knew really clearly was what I wanted my life to be like, I wanted it to have that mixture of inquiry and adventure and competency.”

Her pursuit first took her into foreign languages and then, as an undergraduate, into the study of earth sciences. Back then, around 1970, it was an area still overwhelmingly male-dominated.

“The guys went out to field camps and they dressed all grubby and they never showered and they could swear and be real, rowdy little boys again to their hearts’ content,” she says. Her presence was treated like a disturbance to their fun.

Sullivan felt that by this time, there was already some change under way. She was never, for instance, harassed or bullied for her gender. “In fact, in a couple of key instances, I had some tremendously supportive male professors and colleagues that were definitely, definitely on my side and just saw me as a very capable fellow student, very capable geologist, very capable fellow shipmate.”

Sullivan saw in her marine science professors her ambitions for her own life realised – and so began to further her studies in oceanography.

She applied to Nasa as a way to deepen her knowledge of the earth further still. “My primary motivation for applying to be an astronaut was – if I somehow beat the odds and actually got chosen – I could get to see the earth from orbit with my own eyes.”

Sullivan was admitted into Nasa’s class of 1978. It was the first recruitment drive that brought women into its astronaut ranks.

Six were selected from the class of 35 and Sally Ride, seen on the far left of the image above, became the first of them to fly into space in 1983.

Ride would later recount the unique challenges of being the first women recruited into the space program. Engineers tried to design special make-up kits and wildly overestimated how many tampons would be needed for week-long missions.

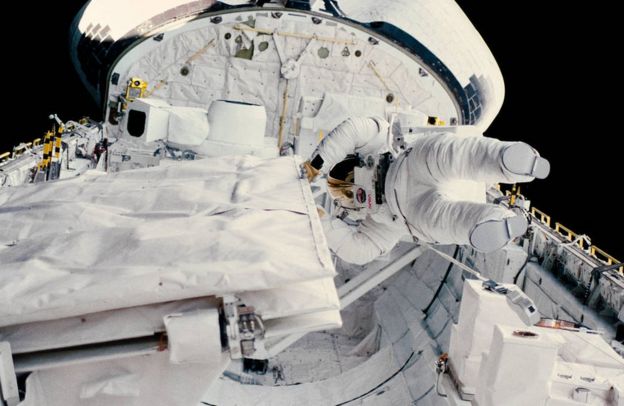

Sullivan’s first mission, STS-41-G, set off on 5 October 1984. It was the 13th flight of Nasa’s Space shuttle program and the sixth trip for the Space Shuttle Challenger.

On 11 October 1984 Sullivan made history when she became the first American woman to leave a spacecraft, along with fellow mission specialist David Leestma, on a spacewalk to demonstrate the feasibility of an orbital refuelling system.

She went on to take part in two more missions, including the 1990 launch of the Hubble Space Telescope. She logged 532 hours in space in total and was inducted into the Astronaut Hall of Fame in 2004.

“My spacewalk was three and a half hours long. It’s a spacewalk that counts but that’s actually very short as spacewalks go,” Sullivan says.

“I was just delighted to see women come after me and do, you know, much more elaborate, much more complicated, much more demanding spacewalks.”

Over the years, Sullivan has also been buoyed to see women increasingly involved at senior levels throughout the space program – including in commanding roles and managing missions from the ground.

“These are all wonderful things and I think help show young girls that you can make your way to these places,” she says. “No one’s promising you a primrose path. You know, you’re gonna have your setbacks, you’re gonna have to persist and persevere.

“You’re going to have to fight back sometimes. But the door is at least ajar – it’s not wide open, but you can make your way through it.”

Last year an all-female spacewalk eventually happened for the first time. It was a nice little “bookend” moment for Sullivan, especially given Christina Koch wore the same life support system backpack Sullivan had all the way back in 1984.

Upon leaving Nasa in 1993, Sullivan went on to serve as chief scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and later as its administrator under President Obama. Between those positions she spent years as president and CEO of the Center of Science and Industry (COSI) and in a distinguished position at Ohio State University.

The surprise invitation for her latest adventure came from Victor Vescovo, a former naval officer and investor who has spent years and millions of dollars on technology to take people underwater, to the depths of our planet.

The Challenger Deep is the deepest known part of the earth’s seabed. Part of the Mariana Trench, it is almost seven miles (11km) below the ocean’s surface, 200 miles southwest of Guam in the Pacific Ocean.

It was first reached in 1960 by two men – US Navy Lt Don Walsh and Swiss oceanographer Jacques Piccard – and has only been reached a handful of times since, including by Titanic director James Cameron.

Vescovo, a keen explorer himself, has said the primary motivation for his private endeavour is to spur interest in the sea and science. Last year he became the first person to visit the deepest points in every ocean using his two-tonne Deep Sea Vehicle (DSV) Limiting Factor, launched from dedicated support ships.

Sullivan said he contacted her via email to invite her on his latest mission, because he thought it was “really time” for a woman to get down there.

She suspects it was her friendship with Don Walsh, the oceanographer first to reach the Challenger Deep, that earned her the recommendation. After researching Vescovo’s endeavour, she excitedly agreed.

Last Sunday she accompanied him down more than 35,800ft (10,900m) inside the two-person submersible – becoming only the eighth person and first woman to reach the bottom.

She describes the journey as like being inside a magic sphere. Seeing the lander – an unmanned robotic vehicle that descends to the seafloor – alongside them at such depth was like stumbling upon “an alien space probe”, she says.

“I mean, it’s just magical that we can go to these places because of the ingenuity and the engineering prowess of these teams of people, we can take our bodies to places that we really have no business being.

“And we can do that, essentially, in street clothes. I mean, I ate lunch 31,000ft below the surface of the ocean on Sunday. That’s crazy.”

EYOS Expeditions, which organised the expedition, also facilitated a call between the pair and the International Space Station (ISS) when they emerged – a fitting representation of the two extremes of humankind’s exploration.

In a press release for the dive, the organisers drew the comparison between Vescovo’s enterprise and what is being done with SpaceX – saying they both show the “exciting potential” of private companies contributing to technological advancement worldwide.

Sullivan believes that as nations and individuals we should continue to push the boundaries of our knowledge about the world we live in.

She also expresses her hope for improved diversity and female representation across the world of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (Stem).

“The stereotype is a very dull person in a lab coat that just knows numbers and just knows principles,” she says. “But in so many fields where science and technology are at the core of what you’re doing, it’s completely creative.”

So does she have any plans for her next adventure?

“I think exploration can take many forms – it doesn’t have to be venturing off physically to the middle of the Pacific Ocean or to the earth orbit,” she says. “There are topics, there are subjects, that there are lots of dimensions to exploring.

“I think I will be exploring until they put me in a little wooden box at some point in the future.”

Credit: Source link