Kenya is a big part of this equation: the country now has nearly 50 million people, and its population is predicted to about double by 2050. And, unlike many of its global counterparts whose populations are rapidly ageing, Kenya’s population is one of the youngest. Its rapidly growing youth demographic isn’t its only defining feature, however: with 44 recognised tribes, Kenya is also among the most ethnically diverse countries on Earth.

Although many numbers tell Kenya’s population story, its shifting demographics may be far deeper and more dynamic than the purely quantitative statistics that define them.

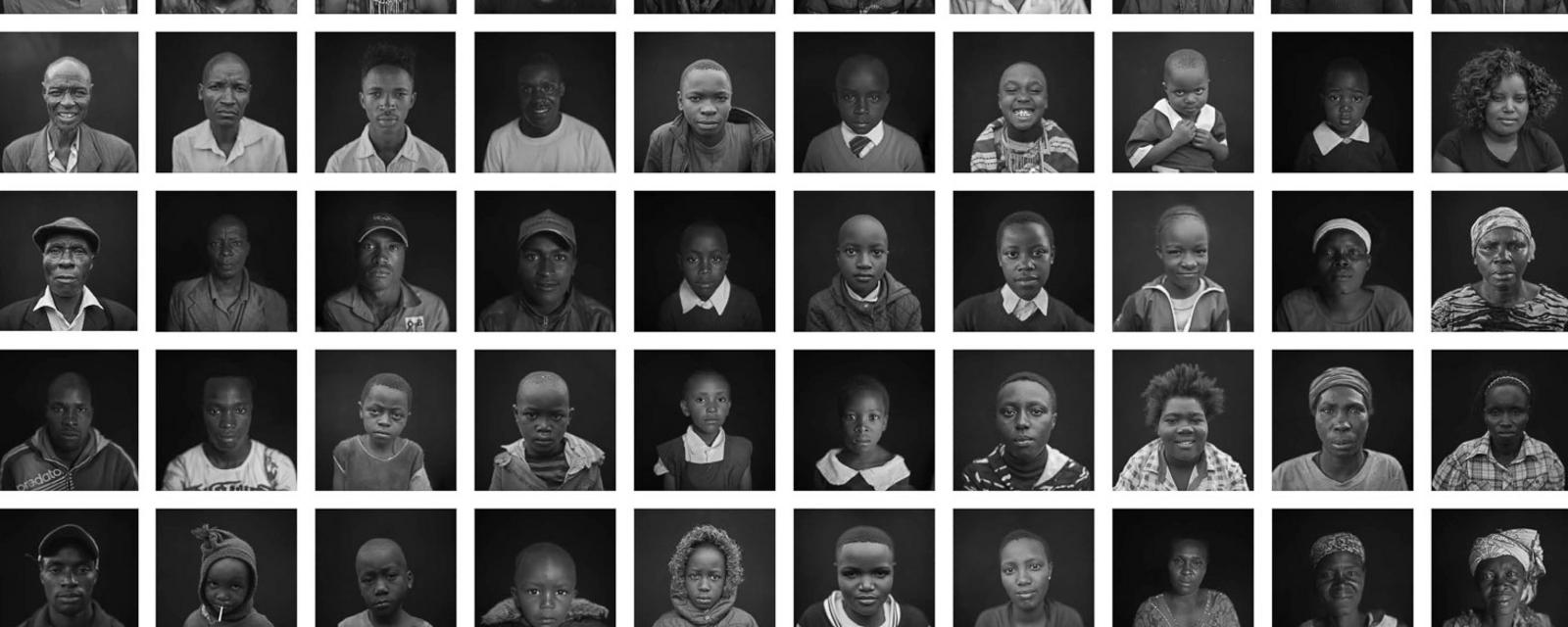

Nairobi-based photographer Tobin Jones, 32, set out to create a vibrant, nuanced representation of Kenya – his 100-image “photographic infographic” called ‘Demographica’ – which aims to put faces and stories to population statistics. Born in Botswana and raised in Malawi and Kenya, Jones has had a front-row seat for Kenya’s massive population changes over the last three decades.

Packing his camera, a black backdrop and stool, Jones drove to all corners of Kenya to capture the subjects who accurately represented the demographics he’d identified, stopping at small villages and along winding roads to collect more complex demographic combinations. He offered each subject an explanation of his project and a copy of the photo in exchange for a portrait.

Covering hundreds of miles and over 12 months, Jones tried to answer the question: what does Kenya look like in only 100 pictures?

Kenya, like many countries in Africa, is incredibly young. Kenya’s median age is only 20 and nearly three quarters of the population – 37.5 million people – is under 30, according to Bernard Onyango, a knowledge translation scientist at the African Institute for Development Policy.

“Kenya is such a young country and you don’t understand that until you see 100 photographs,” says Jones.

In his portraits, 59 feature people 24 years old or younger (representing 29.5 million people), and 34 feature people between 25 and 54 (17 million people). Only four feature people 55 to 64 (2 million people), and just three portraits are of subjects 65 or older (1.5 million people).

Such a young population puts incredible pressure on already overburdened government services like public schools, which are facing swelling enrolment and massive underfunding. And, eventually, the bulge student population will transition into the job market, where a surplus of workers could either lead to accelerated growth or an unemployment crisis.

“I don’t want to use the words ‘ticking time bomb’, but it is certainly is a challenge,” says Bela Hovy, chief of the Migration Section, Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs at the United Nations.

In the Demographica series the number of men and women is split 50/50, an even balance that will remain mostly steady across Kenya in the next several decades.

But despite the equal population split, Kenya is still coping with challenges in equal rights across genders. For example, on average, men make 55% more money than Kenyan women, according to the 2018 World Economic Forum Global Gender Gap Report. Similarly women only hold 9% of all elected positions in Kenya and attempts to pass bills requiring more equal gender quotas have been snubbed by parliament.

Differences like this will pose a problem for not only the growing number of young women as they seek opportunity, but also for Kenya’s future writ large. “We don’t get to tap into the full potential of our women and girls, and so more investment has to be made there,” says the African Institute for Development Policy’s Onyango.

Rapid urbanisation is a hallmark of development across Africa. While about 74% – or 37 million – Kenyans still live in rural areas, more and more are migrating to densely populated cities in search of better employment and education opportunities.

In Demographica, only 26 images represent urban dwellers – about 13 million Kenyans. But change is coming: by 2050, the number of people in cities is expected to increase to nearly half the country’s population, according to the Population Division of the United Nations’ Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

Urbanisation is a natural and necessary step to development, says the UN’s Hovy. However, managing resources and infrastructure planning may be a challenge. Onyango agrees crumbling infrastructure and poor planning will put incredible pressure on city services like water, sanitation and housing.

“The question isn’t whether [urbanisation is] happening or not – it’s happening,” says Hovy. “We have to make sure that it is happening in a way that is sustainable, planned, and that it’s not going to lead to unsustainable overpopulation.”

There are 44 tribes in Kenya, but the majority of the country belong to five: 17% Kikuyu, 14% Luhya, 10% Luo, 13% Kalenjin and 10% Kamba.

Kenya has long been divided by ethnicity, with society shaped along ethnic lines. These divisions have a deep colonial legacy in which tribes were pitted against each other for wealth and land. But they also still persist in society in other ways, such as modern politicians instigating divides to gain votes.

In the past, each tribe has had distinctive customs and culture, often distinguishable by their clothing, last name or the area in which they grew up. This is evident in art, such as Joy Adamson’s collection of paintings in Nairobi’s National Museum, which depict the traditional outfits of tribes in Kenya. Some show the white-painted faces of the Imenti tribe, ears stretched by heavy metal discs. Others feature Kuria warriors draped in muted sheepskin clothes, their feather headdresses curling outwards in all directions as if caught in a strong wind.

But now most Kenyans have swapped their shúkà blankets and animal-skin cloaks for suit trousers and dress shoes, making their ethnic differences increasingly subtle. Of Jones’s 100 photographs, only a handful feature subjects in distinctive clothing, such as the intricate beading of the Maasai people or the long head-scarfs worn by Borana women. Most are dressed in plain shirts or light jackets, their tribes undefinable by appearance.

Many of Demographica’s images reveal that the visual cues that once marked people as certain tribe members may be fading. “I want to show through photographs that it’s really hard to know which tribe someone belongs to,” says Jones. “For most people you have absolutely no idea or clue.”

It may seem ironic in all of Kenya’s massive population growth, but the birth rate is actually falling. In 1978, women were having 8.1 children on average; in 2008, the number had dropped to 4.6. By 2050, that number is expected to decrease to 2.4 children.

But while birth rates are expected to slow in coming years, the overall population of Africa will continue seeing massive growth, reaching more than 2 billion people by 2050.

It’s a tall order to keep a country booming as its population swells. Without proper planning and investments in infrastructure and job creation, critics say that many of these 2 billion citizens will face immense challenges. Others believe that rapid urbanisation, cultural assimilation and careful family planning may offer hope to countries such as Kenya which are facing massive demographic shifts.

“[The future] may seem overwhelming, but let’s not forget the enormous progress that we’ve made,” says Hovy. “I would paint the demographic dividend as an opportunity, and we need to take advantage of that.”

Demographica is part of celebrating that progress. Its depiction of Kenya shows that ongoing shifts in age, gender, tribe and location may actually bridge the differences that once divided the country – or bring it closer together than before.

“What a project like this does is it kind of humanises statistics,” says Jones. “It’s a way of kind of coming to terms with reality and seeing how our world’s changing.

Credit: Source Link