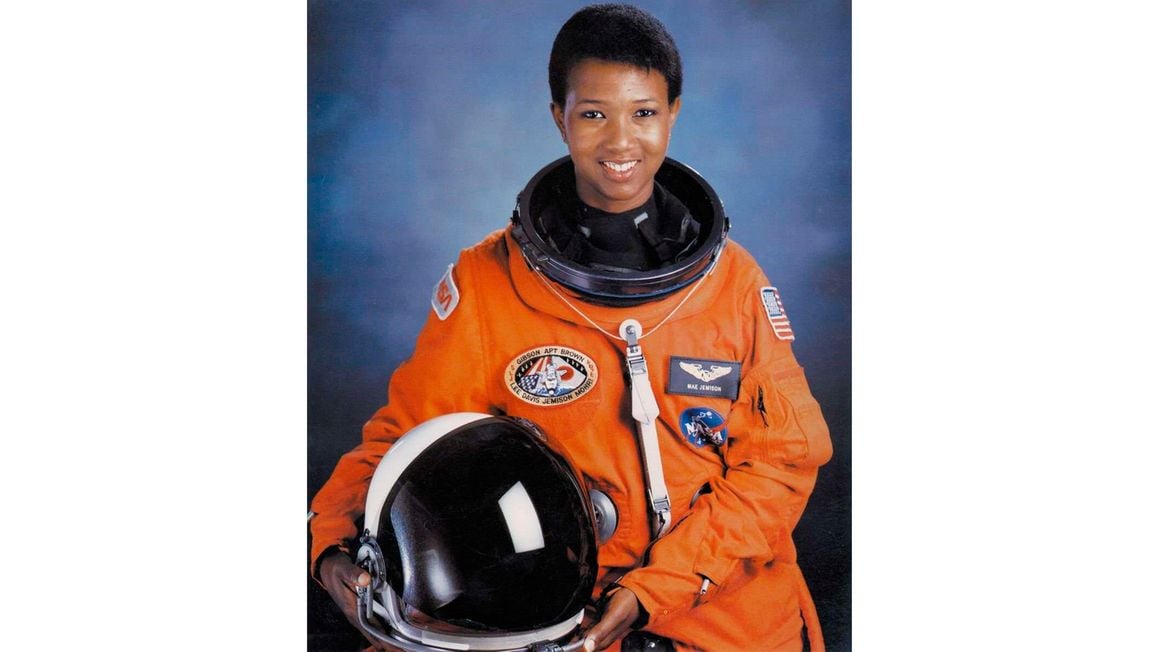

The forceful, vivacious and intense persona of Mae Jemison is hardly surprising to the people she interacts with. Mae was the first black woman in space as a NASA astronaut, where she spent nearly eight days orbiting earth in 1992.

What is surprising, though, is the modesty and guardedness with which she speaks about this historic feat that has made her idolised the world over. She says many pieces go into who we are and what we do.

‘‘I do not think we fully appreciate that where we are today is built on the observations and skill-sets, hard work and accumulation of knowledge of thousands of people who came before us,’’ Mae observes.

She is herself a product of multiple ‘‘pieces of experiences.’’ Before she was an astronaut, she was a doctor and an engineer. Today, she is a public speaker, a businesswoman, a teacher, and an actress.

Mae was featured in Star Trek’s Second Chances as Lieutenant Palmer in 1993, becoming the first real astronaut to appear in the long-running series. She has subsequently appeared in multiple other films and TV shows, including as herself in the 2006 miniseries African American Lives.

At what point do all these disciplines collapse into one?

‘‘When you are in space, you need to know about life sciences, for instance. When we look at the background, we discover that it takes different things to get there. We do not stay one thing our entire life. The things you had to know as a professional early in your career are all changing.’’

Space journeys are a chain of activities and multiple pieces and skill-sets, she explains.

‘‘Astronauts do not do the calculations involved. They do not build the equipment. There are more people involved and astronauts are the public face of the work that goes on behind the scenes.’’

Mae was born in Alabama, grew up, and went to school in Chicago where her family had relocated to. She was three years old. Her memory of her childhood in Chicago is one of fun, many museum visits, and dancing – she has a dance studio at her home in Houston, Texas.

While she was ‘‘a good kid’’ she admits she was not always the best behaved ‘‘because I had a whole bunch of things to say.’’

Her mother was a teacher while her father worked as a maintenance supervisor. She says their confidence fanned her interest in the space. She, however, believes exploration is intrinsic in humans.

‘‘We always do not want to explore the same things or to explore them in the same way. Whether we think about the world around us, whether we explore farming, textiles and designs or economics, and business, it is a part of us.’’

‘‘Every child is born with an inspiration. It is the environment that we (adults) create around them that often drains that inspiration from them,’’ she notes.

She recalls that orbiting Earth was as fascinating as it was reflective. ‘‘I sat there with a huge smile. I wondered what it would have been like if I had met me as a little girl. I knew the girl from Chicago would go to space one day, but I did not foresee the smile she would have when it finally came to pass.’’

She says Project Apollo, the programme that organised trips for humans to space in the 1960s and 1970s, made the difference for her. ‘‘I always assumed I would go to space, even though, at the time, there were neither women nor African American men working in the American space programme.’’

A part of her, she says, has always been connected to Africa. At 26, she volunteered at Peace Corps in Sierra Leone and Liberia, providing medical care to State Department personnel working in the two countries. The first country she ever visited in Africa was Kenya, where she spent three months working at Amref in Embu County, an experience she says reoriented her perspective on life and self.

‘‘When you are in someplace that you did not necessarily grow up and do not know anything about, people can either withdraw or open up to learning. This experience coloured what I do now. It coloured what I knew about space and uses of space.’’

When astronauts go to space, they carry with them different objects that represent different people, organisations, and aspirations. Among the things Mae carried was a flag of then OAU (Organisation of the African Union). ‘‘When I came back, I gave back these items to the people and organisation that may not have been included in the journey to space.’’

She returned to Kenya last month, this time on an even bigger mission. Mae is a leader at 100 Year Starship, a programme that promotes and funds research and technology required for ‘‘interstellar space travel within 100 years.’’

Through this organisation, she has been agitating for inclusion in space programmes for people across ethnicity, gender, geography, and disciplines because ‘‘it is not just one discipline that can do this’’ and that people from diverse backgrounds contribute ‘‘different frameworks’’ for the success of journeys to outer space.

100 Year Starship has had programmes in Africa, Europe, and China and is now planning a major global event in Nairobi in February. On the choice of Kenya’s capital, Mae says Nairobi has a lot of global significance going into the future.

Space exploration, she argues, is more than just launching rockets and exposure is required for people to understand the industry.

‘‘Universities around the world are launching cube sets. Not every developed country has launch capacity. Some of the tracking centres for major missions in space are here in Kenya,’’ she says.

Mae notes that satellite data captured during these missions can have practical applications such as land management even in developing countries that may not have the wherewithal to send astronauts to space.

On the history of women in space, she says Russia had women in space programmes in the 1960s and the US did not allow them until the 1970s. Was there a reason for that? ‘‘They just did not allow them,’’ she deadpans.

Women, though, were always more suited for space exploration than men, she says, citing assessments done by psychologists in the 1960s. ‘‘Their [body mass] is smaller when you look at the load you are taking to space and the oxygen requirements. They would also be more psychologically stable in space. Women also performed better than men in isolation tests.’’

To her, barring women from space had everything to do with sociocultural issues. Are there personal instances when she has been excluded in spaces she felt she deserved a place?

She sighs at length, before noting that detractors do not always have ‘‘to be people who do not look like us’’ adding that even black males have stood in her way. ‘‘Some professors wondered what I was doing in a science class. It did not feel good. But I stayed. If it is something I want to be involved in, I put myself in the situation. It is a personal commitment that I have.’’ she says.

Sometimes it took engaging in ‘‘masculine’’ activities to gel in male-dominated spaces. ‘‘I spent a lot of time with my father playing cards with him. This makes it easier to assert yourself when you get older.’’

She does consider herself fortunate, however, for having been selected out of 2000 applicants to participate in a space programme when opportunities then were so minimal. But to her, that is less significant.

‘‘The question is what do you do when you get in? How do I use my place in the table to ask the questions that need to be asked? Which is to bring your experiences to bear on the questions that are asked, the solutions that are contemplated, and who gets involved. You do that knowing that it is a platform.’’

Credit: Source link