Whoever cared whether their grandmother wore a miniskirt? Or even if their mother wore one in her past life?

Sitawa Namwale discovered recently that many Kenyan women and men do! She found out through the process known as ‘crowdsourcing’. That’s what she calls using all the platforms of social media to invite people to take part in her latest project. It’s entitled “Our Grandmother’s Miniskirt: A People’s History Told Through Photographs and Stories.”

“I got the idea in 2016 while I was working in Rwanda on a project for the World Bank,” says the poet-playwright whose previous careers include professional tennis and development consultancy.

“It was around the time that men were stripping women in matatus, claiming their style of dress was ‘inappropriate’,” says Sitawa.

It was such a shame that Rwandese men and women were shocked.

“They asked me, ‘What’s wrong with your Kenyan men? Why aren’t they protecting their women?’”

It was then that Sitawa began thinking about the integrity of women’s bodies and how, in earlier times, women had worn attire that hadn’t even covered their kneecaps (leave alone their upper body). But they hadn’t been punished for it. It had been considered fashionable at the time.

She also noted that just as these savage incidents against women had inspired her to create her current project, so the ‘My Dress/My Choice’ movement had begun as a direct response to these heinous deeds of violence against women.

In her case, she got curious to find out if Kenyans had old photos of their mothers and grandmothers in their youth. And if they shared them with her, would she be able to verify her view that in earlier times, Kenyan women followed fashions that included attire that matatu touts claim today is only worn by prostitutes.

“The response has been overwhelming,” says Sitawa who already has received almost 100 photographs of grandmothers and moms.

“After they have sent me the photographs, I’ve asked them to also send stories to accompany their photos,” she adds.

That is how she came to exhibit 20 out of the 100 images at Kenya Cultural Centre during the Macondo Literary Festival which just ended last Sunday night. The festival mainly explored ways in which stories reflect people’s history and identity.

And since Sitawa knew that all of her photographs implicitly told stories, not only about grandmothers, but also about what Kenyan life was like in the past, she felt the Festival was the perfect place to see how the public would respond to the project.

“As it turns out, many people expressed interest. Some even promised to send me photos of their grandmothers,” she says, noting her goal is to collect at least 300 women’s photos and slightly fewer stories after which she plans to publish a book.

And through the Dutch organisation, HIVOS, she hopes to network with women from all over Kenya. She’s also elicited interest among Zimbabweans who have invited her to take part in their ‘Women, Wine and Words Festival’ in Harare later this month. There, she’ll present her project much as she did at Macondo and also perform her poetry.

“We’ve also talked about starting a similar project in their country,” she adds.

In the meantime, Sitawa’s crowdsourcing has reaped a plethora of charming stories of Kenyan women whose life histories would have been forgotten if she hadn’t launched her miniskirt project.

Not all the images she exhibited at the festival showed women wearing miniskirts. Some had simply been taken at professional photo studios, like the one of John Sibi-Okumu’s mother, taken just before she and four-year-old John left Kenya for UK to rejoin his father who was studying there.

But others showed women doing progressive activities, like Grace Akinyi riding a bicycle, which at the time (the 60s) was considered taboo.

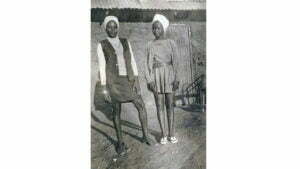

But the show-stopper of the exhibition was the photo snapped in 1945 of the Tharaka woman, Gatoro Ndugi M’Chabari who was decked out in a colourful beaded necklace, an intricately beaded vest and mini-shorts that barely reached the top of her thighs.

“The high point of the show for me was when a young man came up and said she was his great aunt who is still alive at age 95,” says Sitawa who hopes to visit Gatoro soon and learn more of her life and the attitudes towards women in those times.

Credit: Source link