After decades holding the line, the NCAA and the four major professional sports leagues finally lost their battle against the spread of legal sports betting in the United States.

The Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act of 1992 (PASPA) — the federal sports betting statute preventing any state outside of Nevada from taking a bet on a game — died of natural Supreme Court causes one year ago, just after 10 a.m. ET on May 14, 2018.

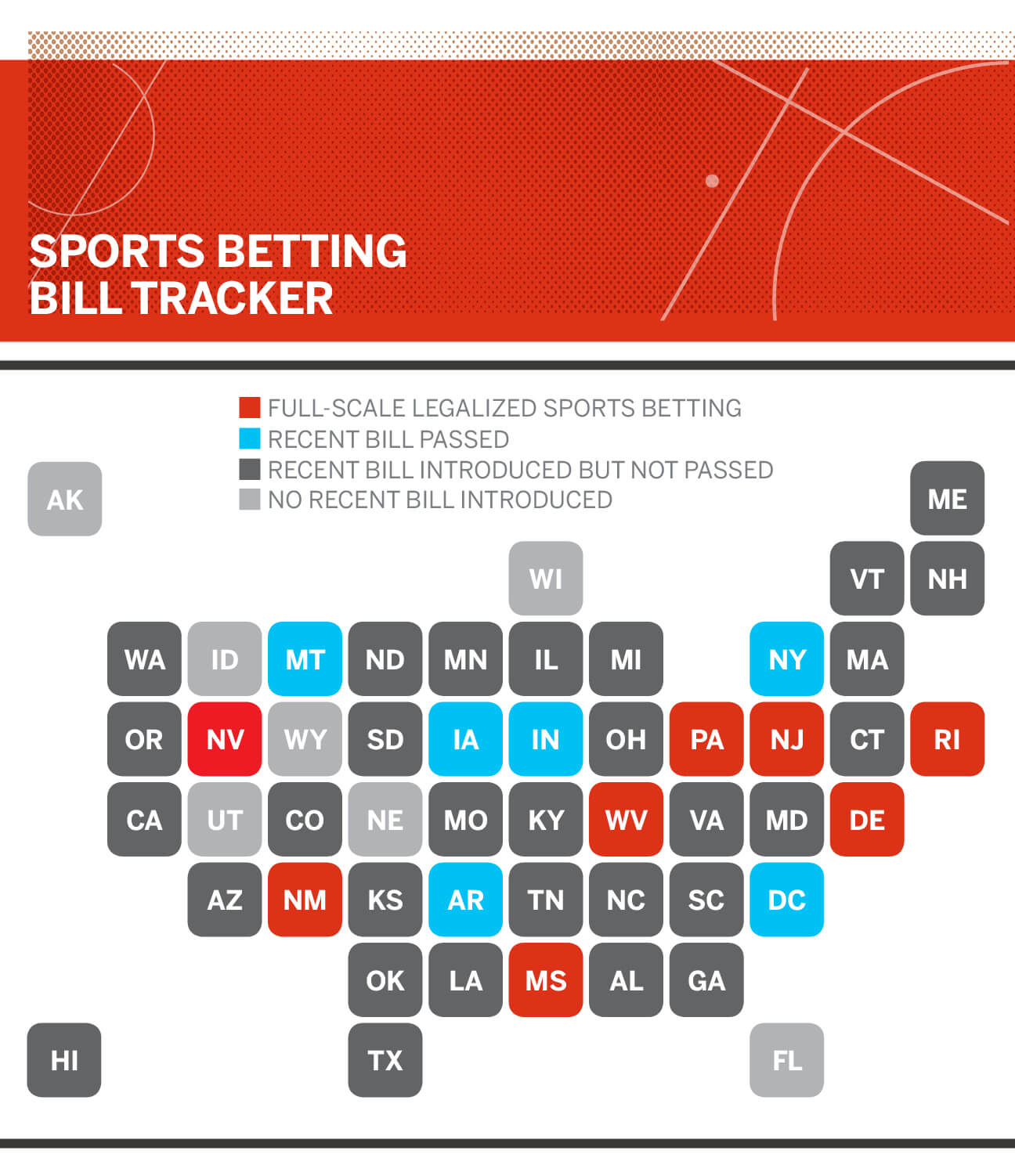

In that short year, seven states (in addition to Nevada) have allowed widespread legal sports betting, and together have taken in more than $7 billion in bets. Montana, Indiana, Iowa and Washington, D.C., have passed legalization bills within the past few days, and several states — including New York — are poised to be next. By 2024, nearly 70 percent of states are expected to offer legal sports betting.

It’s a monumental moment in American sports and already has produced some incredible scenes and storylines:

• Three prominent sports commissioners — the NBA’s Adam Silver, NHL’s Gary Bettman and Major League Baseball’s Rob Manfred — have appeared with the CEO of the one of the largest sportsbook operators in the nation to announce partnerships.

• Two NFL owners entered last season with financial stakes, albeit de minimis ones, in DraftKings — the fantasy giant-turned-bookmaker, which is taking bets on their respective teams.

• Fox Sports announced last week that it will launch a sports betting app and begin taking bets this fall — the biggest move so far by media companies increasingly taking an interest in the industry. ESPN and Fox Sports 1 have already launched daily shows around sports betting.

• Sports betting has been the center of discussion of several huge sporting moments over the past year (Todd Gurley’s kneel-down, Tiger Woods winning the Masters, the Kentucky Derby disqualification, James Holzhauer’s “Jeopardy!” run, among others), raising its profile even further.

1:55

“Jeopardy!” contestant and professional sports bettor James Holzhauer joins SVP to break down his success on the show.

Even given these remarkable developments for the majority of U.S. bettors, not much has changed in how — and with whom — they place their wagers. The offshore and local sportsbook industry remains strong, and larger states such as California and Illinois have been unable to make substantial progress.

“The big story of the year? Sports betting is proving slightly harder to get done than many people — myself included — thought it would be in the aftermath of PASPA,” Chris Grove, managing director of research firm Eilers & Krejcik Gaming, told ESPN. “Chalk that up to the failure of leagues and gambling stakeholders to get fully on the same page, and to the fact that the size of the sports betting opportunity is exacerbating internal industry cracks in the gambling industry.”

Here’s what we’ve learned over the first year of legalized sports betting in the U.S.

Bookies aren’t going away

The late, great Anthony Bourdain described Waffle House as an “irony-free zone” that welcomes “the hungry, the lost and the seriously hammered all across the South.”

On a sunny Wednesday morning last fall at a Waffle House in Roswell, Georgia, everyone looks relatively sober, but there is some irony in the greasy air.

Legal sports betting has begun to spread across the nation. When complete, experts believe the U.S. will be home to the largest regulated sports betting market in the world, a massive, high-tech industry centered on professional and amateur athletics and fueled by hundreds of billions of dollars. For now, though, the fundamental bookie-bettor transaction is getting ready to take place right here at Waffle House.

Across the diner, a nurse in colorful scrubs is choosing between grits and hash browns, bacon and sausage. School buses are going past outside the windows as a landscaping crew shovels in plates of scrambled eggs; a few old timers are drinking coffee at the bar, looking and chatting up the servers like they’ve spent many a morning on the exact same stools.

No one seems to notice when a middle-aged man strolls in through the glass door, wearing a long, navy, wool dress coat and a stylish fedora that is covering all but a few wisps of gray hair. He looks a little out of place, but he’s actually dressed appropriately for his occupation.

Floyd is a local bookmaker. He runs his operation online, providing his bettors with login information to a sportsbook website and an opening line of credit. Bets are placed online, and when the customer reaches an agreed-upon payout threshold, they call or message Floyd. The financial transactions are handled person to person — sometimes through wire transfers or the mail, other times face to face at places like Waffle House.

For many in the U.S., this is how sports betting has taken place for decades, somewhat out in the open but also in the shadows, and mostly out of sight from the IRS. State governments and the influential sports leagues are pushing for change, though. They want their slice of the multibillion-dollar sports betting pie. They want to put Floyd out of business.

Most experts estimate more than $100 billion is bet annually through local bookmakers and offshore sportsbooks. The growing regulated market in the U.S. has handled roughly $7 billion since the Supreme Court decision.

“I still use the same local guy and his website,” a longtime bettor in Georgia said. “I’ve been playing with him for years. He lets me bet on credit. It’s simple, no hassle. Even if they legalized it here, I don’t see myself doing anything different.”

A bumpy road to a mature market

Since the Supreme Court ruling last May, full-scale sportsbooks have opened in seven states — Delaware, Mississippi, New Jersey, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and West Virginia — and several more states (Arkansas, Iowa, Indiana, Montana, New York) are poised to start taking bets later this year. It’s only the beginning of what the NFL has claimed would be a nightmare scenario, threatening the moral thread of sports.

“It is a matter of integrity,” NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue told the U.S. House of Representatives in September 1991 while supporting the passage of PASPA. “It is a matter of the character of our games, of the character of our fans and a matter of values — especially the values that we in professional sports and our athletes represent and transmit to the youth of this country.”

It’s too early to tell if any of Tagliabue’s concerns will come to fruition now that bets are being taken in more states than just Nevada, but while some New Orleans Saints fans might disagree, the integrity of the NFL appeared to survive the first season of the sports betting evolution.

There have been early bumps in the road, though, as the U.S. begins to create a multibillion-dollar market. Among them:

• Political resistance to online wagering has stunted early revenue returns in some states. Only New Jersey and Nevada currently offer statewide mobile wagering. In New Jersey, nearly 80 percent of bets as of last month were placed online or through a mobile app.

• Experts on compulsive gambling are concerned that not enough is being done to protect and treat people who develop addiction through the increased access to sports betting. From July through March, New Jersey’s problem gambling hotline saw an increase in the number of callers who identified sports gambling as either a primary or secondary form of gambling. In November, 25.8 percent of all calls to New Jersey’s hotline were regarding sports betting, including the state’s Council on Compulsive Gambling.

New Jersey’s regulations dedicate 50 percent of funds generated by sports betting licensing to problem-gambling groups, but the majority of states have come up short, Keith Whyte, executive director of the National Council on Problem Gambling, said.

“We’re disappointed,” Whyte told ESPN. “We were hoping all the states that legalize sports betting would take some of that new revenue and dedicate some of it to preventing and treating gambling problems. That has not been the case.”

• International bookmaking companies that have entered the U.S. market have shown their inexperience with American sports and how we bet on them, causing controversies over things like palpable errors and unfamiliar odds displays.

2:05

Nick Bogdanovich joins Daily Wager to discuss the $85,000 bet that will pay out $1.19 million for Tiger Woods winning the Masters.

Little things such as on a Sunday morning in mid-September, one New Jersey sportsbook’s website had second-tier European soccer odds promoted prominently on the front page instead of the NFL odds. Other books have posted “unders” on top of “overs,” somewhat counterintuitive and not traditionally the order in which they’ve been listed in the U.S. for decades.

However, those are insignificant, cosmetic issues. The larger, hot-button issue has been the treatment by some of the new bookmakers of winning bettors who take sophisticated approaches. Books have severely cut limits to dissuade some bettors from playing or banned the pros altogether, something that is a common practice in the United Kingdom.

“I’ve been surprised by how intolerant to sharp action some of these European companies are,” said one professional bettor who goes by the pseudonym Jack Andrews.

Bookmakers in New Jersey and Pennsylvania suggest that once the market matures more, they’ll have more volume to manage sharp action, but, at least in the early going, the bookmaking industry seems to be drifting toward a more hard-line approach to avoiding the smart money.

“Every book is different in how they deal with sharp action,” Charles Gillespie, CEO of international media and affiliate company Gambling.com Group, said. “Some are more afraid of winners than others.”

Aggrieved bettors have taken to social media to express their displeasure and have even gone as far as secretly recording interactions with sportsbook employees who have the unenviable task of delivering the message that their business is not wanted anymore.

Andrews, a longtime advantage gambler, has this advice for bettors who do get limited or cut off altogether: “Don’t make a bad situation worse.”

“We are confident in our bookmakers and how we best use sharp money … it actually makes us stronger.”

PointsBet CEO Johnny Aitken

“Don’t antagonize,” he added. “Don’t make yourself memorable so if an opportunity arises for you to play there again, they are out looking for you.”

PointsBet, an Australian bookmaking company which runs an online sportsbook in New Jersey, has taken the opposite approach to dealing with sharp bettors, and last month began guaranteeing bets to win at least $10,000 for NBA, NHL and Major League Baseball on game days.

PointsBet CEO Johnny Aitken, a veteran bookmaker, said he has been pleased by the early results of what he calls “game-day guarantees.”

“We’ve had some sharp clients sort of appear out of the woodwork and are betting with us every day,” Aitken told ESPN. “We are confident in our bookmakers and how we best use sharp money to shape our book to make the pricing the most efficient it can possibly be. It actually makes us stronger. Since we launched the game-day guarantees, our margins have improved, because our pricing is more efficient early, and that helps us make more money in the long term.”

All of the above will require consistent thought on best practices for the market and all stakeholders. However, the most detrimental issue, experts say, has been the lingering disconnect among the professional sports leagues, the gaming industry and state legislators in regard to what’s best for the overall success of the new American sports betting market.

Disconnect between leagues and stakeholders

On Aug. 7, at a Tuesday afternoon news conference in New York City, NBA commissioner Adam Silver sat next to Jim Murren, CEO of MGM Resorts International, one of the largest sportsbook operators in the U.S. It was the first of a handful of never-thought-you’d-see moments last fall featuring sports bosses and bookmakers buddying up to do business together.

Silver and the NBA were the first league to get involved in the sports betting industry, signing up MGM as an official betting partner less than three months after PASPA was overturned. The NHL and Major League Baseball weren’t far behind, and five NFL teams — the Baltimore Ravens, Dallas Cowboys, Las Vegas Raiders, New Orleans Saints and New York Jets — reached marketing agreements with casinos. Cowboys owner Jerry Jones and New England Patriots owner Robert Kraft even kicked off the 2018 NFL season as investors in DraftKings, which has added casino gaming and traditional betting to its fantasy sports offerings.

This is the new American sports betting industry, where the leagues and their longtime sworn enemies, the bookmakers, are now bedfellows.

But all the sports leagues aren’t on the same page on everything, and neither are all the sportsbook operators. Everyone mostly agrees, though, that two specific issues have been the most divisive: a proposed cut of the action for the leagues and control of the data that is used to fuel the wagering.

• The NBA, Major League Baseball and PGA Tour are seeking a .25 percent fee based on the amount wagered on their events that would be paid by sportsbook operators to the leagues. Such fees first popped up in January 2018 in a sports betting bill in Indiana and were initially referred to as integrity fees, which prompted snarky bookmakers to ask, “Were they not providing integrity before and now need a cut to insure it?” The three leagues now consider the fees a form of compensation.

“Compensation from operators to leagues,” said Dan Spillane, senior vice president and assistant general counsel for the NBA, “recognizing the value that we create, the risks we take on and the expenses we occur.”

The NFL and NHL have not sought any such a fees, and the NCAA also has said it is not looking for a percentage of the amount wagered on college sports, but several of its member schools have expressed interest in receiving a piece of the sports betting pie. Bookmakers point to their small margins of 4-6 percent and insist that there is not enough room to cut in the sports leagues.

“It’s been an uphill battle with the leagues,” Aitken said. “Having that integrity fee or royalty to the leagues based on handle (amount wagered) stymies us from being able to bring back money from offshore.”

• Second, all the professional leagues believe that sportsbooks should be required to use official league data to run their operations and particularly for in-game wagering. The data will be used to generate live betting odds that will be distributed to sportsbooks through league partners. The leagues insist the use of official league data will provide information to bookmakers more quickly and, in turn, allow live odds to have more shelf life. Bookmakers say they’ve been running their business just fine with the commercial data feeds they’ve used for decades. MGM sportsbooks have agreed to use the official league data from the NBA, NHL and Major League Baseball. The leagues are still lobbying to have data rights mandated in legislation. As of mid-May, only Tennessee had passed legislation generally requiring sportsbooks to use official league data.

The development of the U.S. legal market remains a priority for the NBA, according to Spillane, who maintains that there are more areas of agreement than disagreement between the leagues and gaming operators.

1:14

Scott Van Pelt explains why despite being inclined to always root against the house, he doesn’t back a fan’s claim for a large payout over a technical glitch.

“I think that was true at the beginning of the year, and I still it’s true today,” Spillane said in a recent phone interview with ESPN. “Everyone has an interest in crowding out illegal betting markets and shifting people from offshore to legal and regulated domestic betting products.”

MLB says partnerships between the gaming industry and sports leagues should aim to push people into the new legal market, even potentially through league-backed public service announcements.

“Over time, those offshore sportsbooks that have been the only ones for people who wanted to bet were aware of will fade a bit in prominence,” Kenny Gersh, executive vice president of gaming and new business for MLB, told ESPN. “The legalized books will be allowed to market to new fans for sure and hopefully be able to transition some of the existing bettors as well. We are open to doing PSAs about the dangers of giving your money to an offshore operator versus the safety of using a book in the U.S.”

Opinions vary on whether the two sides have made progress on the issues of compensation to the leagues and official data mandates, but everyone involved stresses that it’s early in the game.

The American Gaming Association (AGA), which represents the casino industry and has been an advocate for expanded legalized sports betting, says progress between the leagues and sportsbook operators is being made and points to some of the shifting language in legislation supported by the leagues.

“I think we’re in the second inning of a nine-inning game. We haven’t seen a bill passed that we really think is going to create a best-in-class sports betting market.”

Bryan Seeley, MLB vice president and deputy general counsel

“The initial bills [that the leagues supported] had all sorts of insane requirements about sharing information, control over bets,” Sara Slane, AGA senior vice president, told ESPN. “There was a laundry list of things that were just absurd. I think [the leagues] have scaled back.”

Bryan Seeley, MLB vice president and deputy general counsel, said he wasn’t sure if progress has been made on the disconnect between the leagues and gaming industry. Seeley said he also remained concerned about the gaming industry’s seeming insistence on growing the betting market on minor league baseball.

“I think we’re in the second inning of a nine-inning game,” Seeley said. “For our perspective, we haven’t seen a bill passed that we really think is going to create a best-in-class sports betting market. We’re still hoping to see that bill passed somewhere this year.”

Sports leagues, states and bookmakers ultimately all have the same American sports betting dream: creating a thriving, efficient and lucrative sports betting market that protects the integrity of the underlying games, generates revenue and drives fan engagement. They just don’t all agree on the best way to get it done.

While they figure it out, the underground sports betting world will continue to serve the majority of U.S. bettors.

Back at the Waffle House in Georgia, Floyd doesn’t seem worried about any of it. He knows the new regulated books in other states are going to have a difficult time competing with what he can offer. Betting on credit and somewhat anonymously will always be more attractive than forking over cash and ID to a casino to get down big on your lock five-teamer.

Through black-rimmed glasses perched on his pointy nose, he scans the room, searching not for a place to sit but for someone. A customer sitting alone in a booth looks up, makes eye contact with the man and says, “Floyd?”

Floyd strolls over to his client, shakes hands and declines to sit down for a late breakfast. “No, I got to go,” he says, before casually sliding a white envelope across the table with just under $1,000 in cash inside.

“That’s yours,” he says, and then heads for the exit, looking back only to add, “Send me some more players.”

Credit: Source link