It’s either magical or biological. At least, that’s what they’ll tell you.

After Real Madrid lost 4-3 in a first-leg Champions League semifinal against Manchester City that easily could’ve produced a bigger deficit, Karim Benzema evoked the supernatural. “A defeat is never good,” he said. “The most important thing is we never gave up until the end. … Now we have to go to the Bernabeu. We’ll need the fans like never before. We’ll do something magical, which is to win.”

And what better way to describe what unfolded in the second leg?

City went up 5-3 on aggregate with a goal in the 71st minute, and Madrid didn’t come close to threatening the opposition goal during regular time. Then in injury time, Madrid scored with their first two shots on target of the game to send it to extra time. In ET, City defender Ruben Dias, then the defending Premier League Player of the Year, quickly gave up a silly penalty, and it was game over.

After advancing to the final, Luka Modric reached for a more organic explanation. “The most difficult one was the one against Manchester City because there was almost no time left, but the team and the fans believed until the end because it’s part of the DNA of this club.” He didn’t shy away from the paranormal, either, adding, “The most fun was the PSG game; it was 15 or 20 minutes of madness because it’s very difficult to explain what happens on Champions League nights at the Bernabeu. It was the start of many magical nights that have taken us all the way to Paris, and hopefully we can win another Champions League.”

In the round of 16, Paris Saint-Germain dominated Madrid in the first leg in France, then did the same in the first half in Spain, roaring out to a 2-0 aggregate lead thanks to a pair of goals from Kylian Mbappe. VAR and a couple inches of space were all that prevented the gap from being even bigger … and then Madrid scored three second-half goals in 17 minutes to flip the tie on its head. In between, Madrid blew a 3-1 lead at home and went down to Chelsea 3-0 at the Bernabeu — only to score in the 80th minute to salvage some extra time, where the DNA or the magic took over once again, and Benzema scored the winner.

A couple of questions ahead of Saturday’s Champions League final against Liverpool: Is this improbable run actually magic? Is it dumb luck? Do players gain some sort of innate ability to execute at the highest-leverage moments possible when they put on the all-white kit?

The beauty and terror of it all is that no one knows for sure.

“Luck” vs. “DNA”

If you want your brain to experience physical pain, and if you want to feel like your intellectual capacity is truly inadequate, you should fly to New Mexico and go hang out at the Santa Fe Institute. Founded in the 1980s, SFI is a research center that focuses mainly on complex systems science. As they describe themselves: “Our researchers endeavor to understand and unify the underlying, shared patterns in complex physical, biological, social, cultural, technological, and even possible astrobiological worlds. … As we reveal the unseen mechanisms and processes that shape these evolving worlds, we seek to use this understanding to promote the well-being of humankind and of life on earth.”

At SFI, the evolutionary biologist Jessica Flack studies and teaches the specialties of collective behavior and natural computation. Put in her words: “I study how nature computes solutions to problems & how these computations are refined over evolutionary and learning time.” Put in my words: We have a good idea of the way collective groups of organisms behave, and there’s a lot of research behind why they behave a certain way, but Flack’s work is focused on the nitty-gritty of how those groups behave. What is actually happening when a group of individuals combine to overcome a problem, and how do you rigorously describe it?

Back in November of 2020, Flack co-wrote an essay for Aeon magazine with Cade Massey of the University of Pennsylvania titled “All stars.” The sub-headline: “Is a great team more than the sum of its players? Complexity science reveals the role of strategy, synergy, swarming and more.” The essay delves into all of the things we don’t know about team sports, whether they be unknowable or impossible to measure. It cautions against just writing off unmeasurable phenomena as “luck” and, well, based on what’s measurable in soccer, Madrid’s current run is filled with luck.

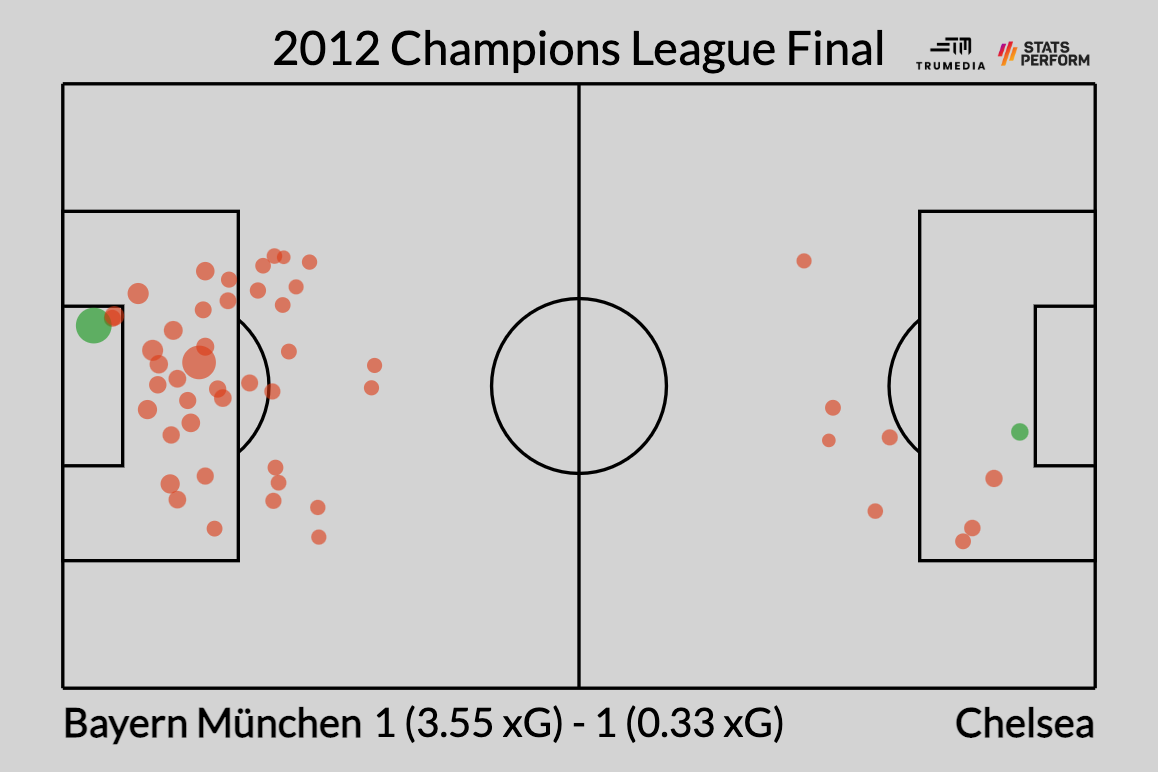

Among the 44 teams that have reached the Champions League semifinals over the past 11 years, this year’s Madrid have the fifth-worst expected goal differential at minus-2.5. Only three teams allowed more goals than the 11 Madrid have conceded, and their field tilt — share of all the final-third passes completed in a match — is 36%, the third-lowest among all 44 teams. The only finalist that grades out worse by xG differential or field tilt is 2012 Chelsea, who of course won the title … but finished sixth in the Premier League and beat Bayern Munich via penalties in one of the most improbable soccer games of the past two decades.

When I asked Flack — not a soccer fan — about Real Madrid this season, I described them as a team that would get outplayed for the vast majority of their matches, only to suddenly coalesce at the last second to produce enough decisive moments and win each match-up by the bare-minimum margin.

When I asked Flack — not a soccer fan — about Real Madrid this season, I described them as a team that would get outplayed for the vast majority of their matches, only to suddenly coalesce at the last second to produce enough decisive moments and win each match-up by the bare-minimum margin.

“We see that some individuals in other domains are very responsive to positive reinforcement or negative punishment and change their behavior in response to that kind of reinforcement,” she said. “And so it just could be that when this group of guys get a little positive feedback, they really ratchet it up.”

This jibes with the “Real Madrid DNA” that all of the players talk about — and also with the management style of Carlo Ancelotti, who is the ultimate “players’ coach,” as shown by Mark Ogden this week. There’s clearly some positive reinforcement that the players get purely from playing for Real Madrid. If you keep telling yourself that your team is special and all your teammates are telling you that your team is special, you eventually start to believe it.

After Madrid beat Atletico Madrid in the 2014 final, thanks to a last-second Sergio Ramos goal that sent the match to extra time, fullback Alvaro Arbeloa said: “This is what Real Madrid is all about. When everyone thinks we are dead and buried, we go and win the Champions League. Real Madrid is synonymous with the Champions League. That is why we are the best.” A year later Toni Kroos, who wasn’t even on the team in 2014, said, “we are Real Madrid and being successful is part of our DNA.”

It might sound hokey, sure, but athletes aren’t just a set of static and consistent inputs that produce an output. Their performance varies from game to game, and often from minute to minute.

In 1985, a group of researchers — including the legendary Amos Tversky, who helped advance the field of behavioral economics — coined the “hot-hand fallacy,” which essentially suggested that the idea that certain basketball players were more likely to make the next shot after a previous make was just a misunderstanding of randomness. You flip a coin enough times and you’ll get 50 heads in a row — that kind of thing. Their studies found no change in field-goal percentage based on the previous outcome. It was just more evidence that, to them anyway, the “hot hand” was just another inaccurate story we told ourselves as we tried to make sense of the world.

However, professional basketball players weren’t swayed by the research and have spoken about the “hot hand” for as long as people like me have been recording what professional basketball players were saying. And then, in 2015, a new group of researchers found that we should actually expect players to miss a higher-than-average percentage of the shots after a make; the players who simply maintained their average across all shots were, in fact, experiencing some kind of hot-hand effect.

But even that research is inadequate to Flack.

“The problem with all of these analyses is that they’re just statistical,” she said. “And so, I’m the kind of scientist who builds mechanistic models of phenomena like this. What I never see discussed in this ‘hot hand’ discussion is a neurophysiological model that might support transitioning into a ‘hot hand’ state. We want to know if, aside from behavioral evidence for the hot hand, there are underlying neurophysiological changes that suggest a person’s entering the state and that being in that state increases their focus or their understanding.”

With sports, we can measure what happened; like with everything else she studies, Flack wants to know how it happened. With almost all sports analysis, we, to put it crudely, have no idea what’s going on with a player’s body or a player’s brain. Other research has found that brain activity among students in the same classroom will become correlated. When friends are shown the same image, their brains respond much more similarly than when compared to two people who are not friends.

Could Madrid’s players, through this collective identity they’ve established, have a way of finding their own kind of hot hand, all at the same time?

“Through synchronizing their behavior, the whole team could become ‘in flow,’ or ‘hot,'” Flack and Massey wrote. “This might seem far-fetched, but it regularly happens in nature … [including] the coordinated chorusing of frogs and circadian rhythms. So why shouldn’t it happen in sports?”

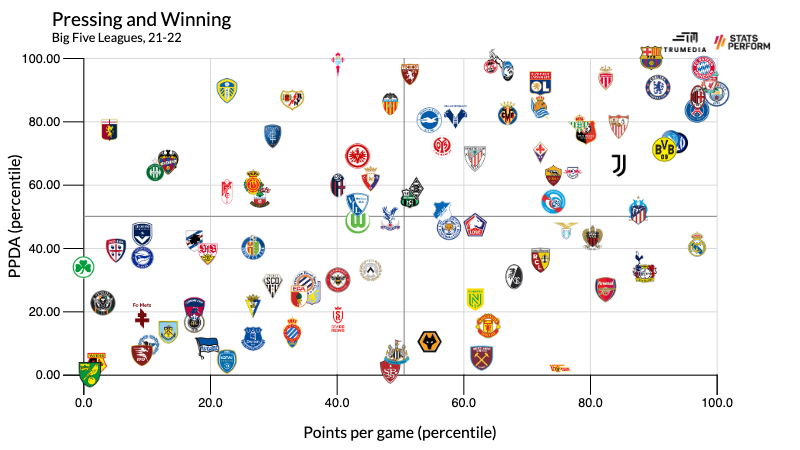

Flack also wondered aloud if “there’s something about the style of Real Madrid’s play that’s more entropic [defined as “having a tendency to change from a state of order to a state of disorder”] or less predictable than the style of other teams play.” It certainly is. A coordinated press is a decent indicator of a rigorous and structured style, and among the best teams in the world, Madrid stand out for how little they press. The higher you go in this chart, the more aggressive the press.

Ancelotti is famously much less strict from a tactical standpoint than other managers who have achieved similar levels of success. After Pep Guardiola was replaced by Ancelotti in Germany, the players at Bayern Munich were upset that Ancelotti wasn’t demanding enough. There are fewer predictable patterns in the way Madrid plays than other top teams, and it often feels like they are a group of world-class players figuring it out as they go. Could that play a role in Madrid’s ability to surprise teams that, on aggregate, have performed at a much higher level? Perhaps a level of unpredictability combines with the collective belief that they can win from any position?

Ancelotti is famously much less strict from a tactical standpoint than other managers who have achieved similar levels of success. After Pep Guardiola was replaced by Ancelotti in Germany, the players at Bayern Munich were upset that Ancelotti wasn’t demanding enough. There are fewer predictable patterns in the way Madrid plays than other top teams, and it often feels like they are a group of world-class players figuring it out as they go. Could that play a role in Madrid’s ability to surprise teams that, on aggregate, have performed at a much higher level? Perhaps a level of unpredictability combines with the collective belief that they can win from any position?

“If they’re individual players making decisions on the fly, it could be synchrony on a different level,” Flack said. “It could be asynchronous in their synchronized emotional states, but asynchronized behavior.”

On Saturday, Madrid will come up against arguably the best team in the world. For their part, Liverpool have worked with a German neuroscience company to help with execution on set pieces and Jurgen Klopp routinely refers to his own team as “mentality monsters.” But more simply, Liverpool have played the maximum number of games possible this year and have only lost three times. Madrid, meanwhile, lost three games in just the Champions League knockout round. For those reasons, FiveThirtyEight’s prediction model gives Liverpool a 65% chance of winning, while the betting markets have them as closer to a 60% favorite.

Should those numbers be closer to each other? Are the aggregates missing out on Madrid’s ability to coalesce when it matters most?

“There’s a lot of interesting questions here,” Flack said. “But I don’t think there are a lot of answers yet.”

Credit: Source link