In a social media environment flooded with fake information, millions of Kenyans who spend most of their time online are finding it difficult to discern between what is true and what isn’t.

It should be a source of concern, given that it is happening during this crunch time, just a few months to the 2022 general elections.

For instance, did ODM leader Raila Odinga dress like a sorcerer or did Deputy President William Ruto’s car hit and kill a pedestrian in Kiambu a week ago? What about Interior Cabinet Secretary Fred Matiang’i? Has he declared that he is running for president, and is Kirinyaga governor Ann Waiguru his running mate?

None of these claims are true, but they have been spreading on social media with some created deliberately to spread misleading narratives.

The political battle of the day is being fought on social media and one of the weapons being deployed is disinformation.

Politicians mobilise and pay youth to post tweets using pre-selected hashtags and spread falsified information, push misleading narratives or drown out genuine discussion.

Studies examining the influence of disinformation on the political process abound. The admission and revelation by Cambridge Analytica that they played a part in the influencing the election in 2017 election is one example.

There was subtly admission by the firm that they used psychological manipulation, entrapment and fake news to influence the polls.

In a paper reviewing how disinformation impacts politics which was published by the International Forum for Democratic Studies, Dean Jackson cites the Kenyan case during the 2017 campaigns as an example of the widespread use of domestically sourced disinformation in an electoral context. Rival political factions created sophisticated digital operations, conscripting influential social media personalities, paid commentators, and armies of bot accounts.

“Digital advertising techniques amplified the spread of hate speech and disinformation targeting political opponents. Hoax websites imitating real news outlets produced disinformation at an industrial scale, with one study finding that nine in ten Kenyans had seen false information about the election online, and 87 per cent of respondents believing that information to be deliberately false,” he writes in the paper.

The study observed “a sophisticated underground” public relations industry in which digital strategists, social media influencers, and paid commenters compete to deliver their clients the greatest degree of control over political narratives on the internet.”

But the 2022 campaigns are not any different. Kenyans will feel a sense of déjà vu – the paid commentators, bot and sock puppet Twitter accounts as well as hoax websites are back as the country slowly gets into a what will be a hotly contested election.

The attempt to review the constitution through the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) offered a glimpse at what Kenyans can expect to see during the campaigns.

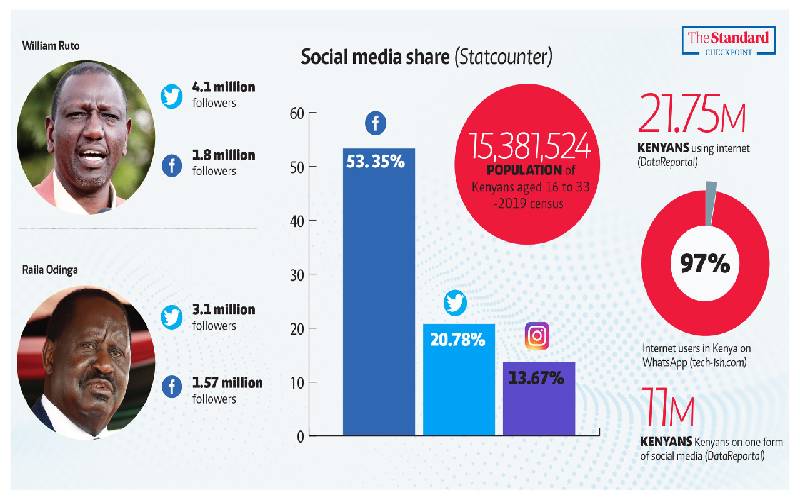

Ruto and Raila have already emerged as the leading contenders to succeed President Uhuru Kenyatta. They have all been victims of highly coordinated campaigns on social media. The campaigns not only pursue political objection, but they also amplify social division and build resentment and fear.

Hashtags such as #RutosLyingTongue, #RailaHatesMtkenya, #ArapMwizi or #Kigeugeu are becoming commonplace courtesy of a network of faceless accounts.

Credit: Source link