“My husband shouted at me: ‘You don’t care about dying, about leaving me and your mother!’ I replied: ‘No I don’t. I just want to live my dreams.'”

Mercedes Maidana had become obsessed with chasing the big waves. It gave her a buzz. Each time she went out surfing she would risk more and more. Until one day, it all went wrong.

On 12 March 2014, Maidana took part in the Nelscott Reef Big Wave Classic, a competition for the world’s best on the United States’ Oregon coast.

“I got caught out by a 30ft wave and just froze,” she says. “It took me all the way down under water and my surf board crashed into my forehead.”

Maidana was rescued but was bleeding heavily. Once back on shore, she was taken to hospital. The doctor glued the cut above her eye. He said she had a “mild concussion, nothing to worry about” and discharged her.

But Maidana knew something was “off”.

“Straight after the accident I couldn’t put my finger on it, but that night I threw up many times,” she says. “I got rushed back to hospital where they did another scan – but, again, they said I was fine.”

Things were far from fine. As the days passed, back home in Hawaii, Maidana’s condition got worse. She had less and less energy. She could not hold a proper conversation, text or even walk her dog. She became confused, paranoid, anxious and depressed. Each time she went to see a doctor, they told her to rest and gave her antidepressants.

“I lost everything in my life,” she says. “I lost my career. I lost my health. I got divorced. I lost my all my money. I even lost my dog.

“I had suicidal thoughts and it was scary because I probably had them for two years. It was one consistent thought.”

After nearly two years, Maidana was still sick and close to giving up. There seemed to be no explanation as to what was wrong with her. Nothing was working, so she decided to contact another surfer – Shawn Dollar. Dollar was also in recovery after being injured in a big wave accident.

“I always describe him as my life saver,” Maidana says. “The most important thing was he showed me that he didn’t give up. I was already at that point when I was going to give up. I thought I was going to live my whole life feeling horribly concussed – which means fatigued, depressed, anxious. Everything was impossible to do. I thought: ‘OK, I just have to wait it out until I die and I hope that happens quickly.’

“But when I hung up the phone, I just felt embarrassed to throw in the towel. I thought: ‘OK, if he’s doing it, I have to do it too.’ That was the most important piece of the puzzle.

“He guided me to a concussion foundation in California. The lady that guides the foundation, Jill, was like an angel. Every step of the way she was guiding me, every day of the year.”

Maidana’s condition began to improve. She soon felt strong enough to make a clean break, thinking the change would do her good. She was wrong. It turned out she was only at the start.

In February 2016, Maidana decided to move away from the beaches of Hawaii. She accepted a job in Texas selling life insurance.

But the long hours and stress of working on commission drained her, and she quit after six months. She still wasn’t getting any better. She decided she had to commit everything to her recovery.

She tried new treatments. She had oxygen pumped into her blood – “I needed it to heal my brain”. She went to see neurologists – “I had to rewire my eve movement”. She had treatments to adjust her spine. For a full year, for six hours a day, she says her “job was to recover”.

At last she began to see improvement – but it soon slowed. The old symptoms were coming back. What was happening?

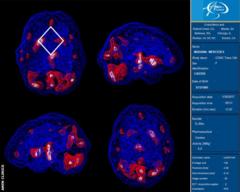

“I ended up going to a clinic in California and they did Spect (single-photon emission computed tomography) scans to see what was really going on inside my brain – which parts were active and which were asleep,” she says.

“My brain was pretty much healed, but I had severe PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder). The recovery plan changed to focus on emotional health, and that’s when they changed my diet completely.

“I came off sugar, dairy, any processed foods and alcohol. I had to eat very clean. I was given supplements to improve my brain function, like fish oil and different vitamins, and therapy to deal with my emotions. They put me on the right kind of antidepressant. I started to recover very fast shortly after that.”

PTSD is something many people associate with the military, and not something you expect to hear about in surfing. For Maidana, the definition – “an anxiety disorder caused by very stressful, frightening or distressing events” – began to make sense.

Before her big accident in 2014, Maidana did not realise each scary experience was adding to her trauma.

“When you have an injured brain you can’t be inside a washing machine and have it rattle all over the place,” she says.

“I was creating concussions over concussions, because every time I fell from a wave it would rattle my brain. I once got stuck in a reef cave and nearly drowned. I was very traumatised by that. I would start crying anywhere, like the supermarket.

“Another time, we lived overlooking the beach and my husband had an eerie feeling when he was watching TV. He looked out and saw my purple surfboard floating into the horizon, and ran out to find me lying on the shore bleeding.

“He kept asking for me to stop surfing in big waves because I kept having serious accidents and he was scared for my life. But I never listened to him. He begged me not to go to Maui. He said these are huge waves, you are not ready, this is not for your level. And that was the truth, I wasn’t at that level. But I didn’t listen and went anyway.

“I surfed a wave that was about 35ft, ended up in the impact zone and then three waves that were 50ft tall crashed on top of me. Someone on a jet ski came to save me but then the engine cut out and we got mowed by another 50ft wave. That day I thought I was going to die. I felt I was underwater forever. I came back home and I said: ‘I almost died.’ My husband was so angry at me.

“He said: ‘You don’t care about dying, about leaving me and your mother if you die.’ And I was like: ‘No I don’t. I just want to live my dreams.’

“I was on a path of self-destruction, and he was witnessing that for years. Now, with perspective, that day in Maui I see I lost my limits, I didn’t die and I realised I wasn’t afraid of dying any more. That was dangerous.”

Nine days later, against her husband’s advice, Maidana went to Oregon for the Nelscott Reef Big Wave Classic, unaware this would be her last competition.

“I thought I was indestructible,” she says. “Death was no longer a big deal. I was out of my mind. So when I returned home after another near-death experience, my husband could see I just wasn’t listening and had no intention of stopping my obsession with big wave surfing. After a few months, we separated.

“In a way, I’m glad I got the concussion. I was on a path of self-destruction without even knowing it. Now I see what I was doing was nuts.”

The International Surfing Association acknowledges concussion is “an important matter for surfing”. It says “the welfare of athletes is always our primary concern”.

The organisation says all its events are “closely monitored” by “experienced medical teams” who “always carry out injury prevention and management protocols onsite if an incident is suspected to have occurred”.

It also says it plans to “advance our work with medical experts” to ensure concussion protocols remain “at the highest standard” in the context of increasing awareness of, and research into, the dangers of head injuries. Maidana is keen to help raise that awareness.

“There are so many people who don’t know they are suffering from concussion,” she says. “It’s an invisible injury, which is why it’s so complicated. People don’t understand it.

“In surfing, people need access to this information so they know what to do if they get concussed. You need to be vigilant. What happens in the next months, not just days and weeks? Is your personality changing? Is your mood changing? Your energy levels?

“I don’t think it’s realistic to say we should all wear helmets all the time, as there is something about surfing where you just want to be free, natural with the elements. But I do feel that when there are very shallow reefs and powerful waves, you definitely should be wearing a helmet – and in big wave surfing it would be a great advance.

“The Concussion Legacy Foundation asked for athletes to donate their brains. When I die I don’t need it, so I hope that helps give many answers.”

Maidana, 38, does not get too many “buzzes” nowadays, but that is fine with her. She is working as a stylist.

“I’m rewiring my brain, slowly, to be able to be happy and content with a simple life, without the huge ups and downs and adrenaline rushes that were very fun but came with huge emotional and physical costs.

“The most similar ‘buzz’ I do get is from playing the bass guitar. I stopped playing for 15 years as I was so immersed in surfing, but when I was dealing with depression I had a lot of insomnia so I started playing the bass at night to pass the time. I love it.”

Maidana still surfs. But she sticks to the smaller waves, which is something she never thought would be possible before her accident.

“Without surfing I thought I wouldn’t have an identity,” she says. “I didn’t know who I was if I wasn’t a big wave surfer, which is really sad.

“Now I’m discovering I’m a human with a lot of qualities. It’s about surrounding myself with loving people and doing things that make me happy.”

Credit: Source Link