If your morning can’t start without coffee, you’re not alone: globally, we drink over 2 billion cups of coffee each day, leading to 60 million tons of wet, spent coffee grounds every year.

Only a small portion of this is reused — mostly as soil fertilizer — with the vast majority being incinerated or ending up in landfill. There, like other organic compounds, coffee grounds decompose and release methane, a greenhouse gas 25 times more powerful than carbon dioxide at trapping heat.

Now, researchers say coffee grounds could be used as an ingredient in concrete, and they could even make it stronger, according to a recent study.

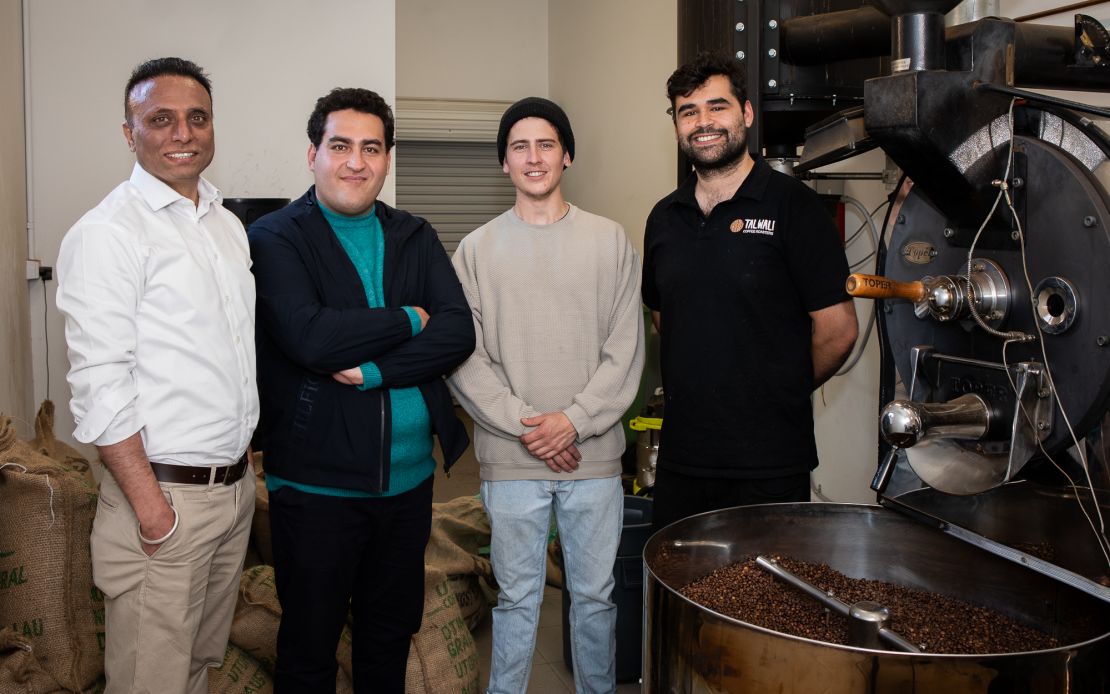

“We thought of this idea over a cup of coffee,” says Rajeev Roychand, a research fellow in the School of Engineering at RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia, who led the study. “We roasted the spent ground coffee in the absence of oxygen, and obtained something called biochar. When we added it to concrete as a replacement of sand, it provided a 30% increase in the strength of the material.”

Tiny reservoirs

Concrete is made of four basic ingredients: water, gravel, sand and cement. It is the world’s most widely used building material, and we go through 30 billion tons a year, three times as much as 40 years ago.

Roychand and his team partially replaced sand with biochar — a material similar to charcoal — derived from coffee waste; they obtained their best result when they replaced 15% of the sand and baked the grounds at 350 degrees Celsius (662 degrees Fahrenheit). The resulting concrete was 30% stronger than regular concrete by compressive strength — the ability of the material to withstand a load.

In regular concrete, water, its second-largest ingredient by volume, is absorbed by the cement over time, reducing the amount of moisture that’s still inside the concrete, Roychand says. This drying effect, known as desiccation, causes shrinkage and cracking at a microscale, weakening the concrete.

Biochar from coffee waste can reduce this natural process. When the biochar is mixed with concrete, Roychand says, its particles act like tiny water reservoirs, distributed throughout the concrete. As the concrete sets and begins to harden, the biochar slowly releases the water, essentially rehydrating the surrounding material and reducing the impact of shrinkage and cracking.

“We’d be diverting this waste and transforming it into a valuable resource,” says Roychand. “There is also a scarcity of sand, and even if we replace some portion of it, we are still improving the sustainability aspect, and slowly we may come up to a stage where a significant chunk of the sand can be replaced with different waste materials.”

“High-value by-product”

According to Kypros Pilakoutas, a professor of construction innovation at the University of Sheffield in the UK, who was not involved with the work, the study is intriguing from a technological perspective.

However, he finds it improbable that concrete produced in this way will ever find widespread use in large-scale applications. “The main issue with waste is mainly collection and processing,” he says. “Whilst it would be great to collect all coffee grounds from around a country, the associated costs would be considerable and prohibitive.”

He adds that pyrolysis — the process through which the biochar is produced — is not cost-free, and he believes that it’s unlikely that high concentrations of carbon in concrete would enhance its long-term durability.

Roychad points out that waste collection is already mainstream, and that a number of companies in Australia are focusing on recycling coffee waste. He adds that the cost of pyrolysis is mainly related to the initial investment in equipment, and that biochar is produced at a much lower temperature than cement — 350 Celsius compared to about 1,450 Celsius. “But we are missing other benefits,” he argues, “as the waste material that ends up in landfills requires cost for its disposal. It can now be converted into a high-value by-product.”

The ingredient in concrete that contributes most to climate change is cement — which was responsible for 8% of global CO2 emissions in 2021 according to think tank Chatham House — and Roychand believes that increasing the strength of the concrete by 30% makes it viable to decrease the cement content by up to 10%, reducing its climate impact.

He says that the discovery has already attracted interest from both construction companies and organizations that recycle coffee grounds, and his team is now working with local councils in Australia to start field demonstrations.

“One of the things we will be doing is monitoring the concrete over time, for six months to one year,” he says. “This will make sure that the biochar maintains its properties over time.”

Credit: Source link