The young woman arrived at Southend railway station by third class carriage with her heart set on winning the town’s beauty contest. But her entry would cause a scandal that made headlines around the world. Why? Because the year was 1908 – and she was black.

The manager of Southend’s Kursaal amusement park was sitting in his office when the telegram arrived from Great Yarmouth.

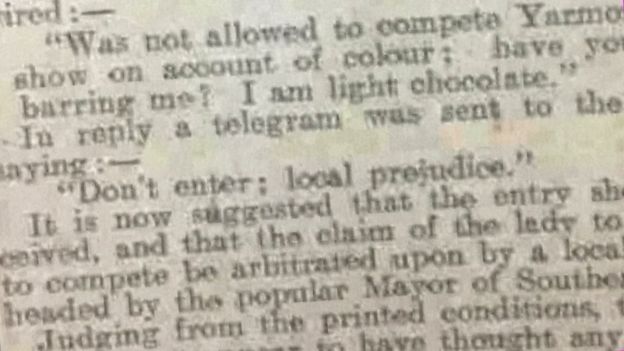

“Was not allowed to compete beauty show here on account of colour,” it read. “Have you any rule barring me? Reply Post Office, Princess Dinubolu, of Senegal.”

Far from impressed by the attention of royalty, the manager’s reply to the mysterious princess was blunt.

“Don’t enter,” he telegrammed back. “Local prejudice.”

But Princess Dinubolu was not to be ignored. She entered not only the ‘brunette’ and ‘best hair’ categories, but also the ‘blonde’ category.

News of her entry soon spread around the seaside town. Many were scandalised when a local committee was unable to find anything in the rules barring her from the competition.

Newspapers in London dispatched reporters to the scene and from there the story quickly spread, even reaching New Zealand.

Such was the press attention that, when the princess came to travel to Southend, she opted to travel third class in an attempt to slip in unnoticed.

Her plan failed, however, and she soon found herself being quizzed by reporters.

Speaking through an interpreter, she said: “I wish to show my people that you are fair to all comers, even if they are chocolate-coloured.

“People have told me that only cream-and-pink little English misses can win, and that your judges have no eye for any other sort.

“I wish to prove them wrong. I have heard that a black baby won a prize in Southend, and I feel sure that they will be kind to us all alike.”

At a time when black people were rarely seen outside the main cities – and racist attitudes were legal – the thought of a black woman entering the local beauty contest was too much for some.

Princess Dinubolu was advised not to enter because of ‘local prejudice’, according to the Sheffield Daily Telegraph

Indeed the story about the black child winning a beautiful baby competition in the town was true. The Kursaal’s manager – a Mr Bacon – complained he had been “absolutely mobbed” by angry residents for weeks after the baby’s victory two years earlier.

Princess Dinubolu’s strange story reveals much about the racism and ignorance that prevailed in much of early 20th Century Britain.

One incident in particular stands out.

When asked by a reporter from the Southend Daily Chronicle to reveal her beauty tips, the princess reportedly replied: “Ah, you will laugh, for my beauty bath is very different from that of the English girl.

“For months I have been staying at Yarmouth, as there is such beautiful sand there, and every morning I am buried to my neck in sand.

“Nothing makes the skin so velvety; the belles of my own country believe very much in sand baths.”

Nobody doubted her tale. In fact newspapers vented their shock that nobody in Great Yarmouth had spotted a woman’s head sticking out of the sand.

Days later, about 3,000 spectators were packed into the Kursaal to watch the 49 contestants take to the stage.

About one third of those entered were from Southend and its environs, according to historian Jeffrey Green, who has studied the story. Another third were from London with the remainder coming from other parts of the UK, France and America.

Among the rivals was a 16-year-old girl called Miss Lessing, who had travelled from Philadelphia and had apparently won “nearly every beauty show in the States”.

Accounts of what Princess Dinubolu wore to the contest differ. Some say she wore “West African robes”, others that was “dressed joyfully in red Turkish fez material with hat to match”.

The Marlborough Express in New Zealand told how “when the Princess arrived in some state a flutter ran through the ranks of her fair rivals”.

Success in the show depended on the response of the crowd. The volume and length of applause would decide the participant’s fate.

Princess Dinubolu was cheered through to the second round. But her success further into the competition foundered.

“When she came forward to the footlights attired in flowing robes there was no howl of derision. On the other hand, there was no enthusiastic applause,” reported the Marlborough Express.

The audience, according to the Southend Telegraph, were “too patriotic” while the Evening Standard declared the princess was “well received, but she by no means proved a formidable opponent”.

Defeated, the princess departed the stage and disappeared from the fabric of history.

But who was Princess Dinubolu? The only evidence for her existence is newspaper reports while no drawing or photograph of her has been unearthed.

Elsa James, an artist in Southend, featured the princess in her recent Forgotten Black Essex exhibition.

“I’m blown away by the fact this one black woman in 1908 just took over the newspapers and she was covered throughout the whole of Britain, just her entering this competition,” she says.

“For me she was just so bold and brave to just take on this white world. Actually, sometimes, with a bit of wit, such as talking about burying herself in sand. I mean that was obviously not true but it was taken as true.

“When I thought about who has that sort of attitude and sass, I thought about women like Beyoncé.

“Why would you enter the blonde section? She wanted a platform, something more than she had, and she got it.”

But was any of it as it seemed?

The princess’s back story, for starters, seems a little far-fetched. She said she had arrived in the UK after fleeing her father who was angry she had entered a relationship with a lower class musician. She hoped to win back her place in her father’s affections by winning beauty contests in England, she claimed.

“Beauty is regarded as the highest gift the gods can bestow on woman, and I hope that if my beauty is admired in England and given a prize my father will be reconciled to me,” she said.

But even if this story seems unlikely, her name is in fact consistent with being from Senegal or elsewhere in Islamic West Africa.

Friederke Lüpke, a professor of African Studies at the University of Helsinki, said the names Djinabou or Djenabou are “very widespread” in this region.

It was also quite common for wealthy black Africans to travel to Europe for work or study, according to Prof Hakim Adi, of the University of Chichester.

While it was more common for black men to make such a journey, it was not unheard of for black women to do the same.

But if Princess Dinubolu was really from Senegal, he said, it might seem more likely she would have travelled to France, as Senegal was a French colony at the time.

As to whether she was a princess or not? Again, the jury is out. There are numerous instances of black people styling themselves as “prince” or “princess” on dubious grounds, said Prof Adi.

“Some people used it to become more exotic,” he said. “And of course there were lots of royal families in, say, Nigeria, so the title of ‘prince’ or ‘princess’ doesn’t have quite the same meaning there as it does here.”

But, of course, the whole, strange story might have been made up.

“My own position is that the whole thing is sort of a fake,” says author and historian Steve Martin, who doubts a real princess would ever have entered a seaside beauty contest.

“The jury is out for the time being as to what the real story was. It is interesting, however, in terms of ideas about race in coastal towns in Edwardian Britain.

“There’s no follow-on in the story,” he said, suggesting once again it was a false narrative.

Was it all a publicity stunt for the event? Possibly, says Mr Martin. He suspects the princess may have been a local mixed-race woman, possibly working in cahoots with the Kursaal’s manager to bolster its takings.

As for Mrs James, the possibility that Princess Dinubolu might have been a local black girl masquerading as royalty from a far-off land merely adds to her appeal.

“For me she was the first ‘#blackgirlmagic’ in Britain because despite what England would have been like then, she was at the top her game,” she says, referring to the social media movement.

“Not winning had nothing to do with it. It was the taking part.”

But if she was real, one woman who possibly understands more than any other what Princess Dinubolu was going though is Jennifer Hosten.

In 1970, the then Miss Grenada became the first black woman to be crowned Miss World.

“Having experienced the impact of a woman of colour winning Miss World in 1970, I can well imagine the challenge that Miss Dinubolu’s participation presented in 1908,” she said.

“Her recognition that a beauty contest could be used as a platform for creating societal change is noteworthy. As was her courage and determination in the face of an enormous challenge.”

Credit: Source Link