For Sudeep Choudhury, work on merchant ships promised adventure and a better life.

But a voyage on an oil tanker in West Africa, in dangerous seas far from home, would turn the young graduate’s life upside down.

His fate would come to depend on a band of drug-fuelled jungle pirates – and the whims of a mysterious figure called The King.![]()

The MT Apecus dropped anchor off Nigeria’s Bonny Island shortly after sunrise. Sudeep Choudhury was at the end of a draining shift on deck. Looking towards land, he could make out dozens of other ships. On the shoreline beyond them, a column of white oil storage tanks rose out of the ground like giants.

He had breakfast and then made two phone calls. One to his parents – he knew they worried about him, their only child – and one to his fiancee, Bhagyashree. He told her that everything was going to plan and that he would call her again later that day. He then clambered into bed for a sleep.

It was 19 April, 2019. The small, ageing oil tanker and its crew of 15 had spent two days sailing south from the port of Lagos to the Niger Delta, where oil was discovered in the 1950s by Dutch and British businessmen seeking a swift fortune. Although he knew that vicious pirates roamed the labyrinthine wetlands and mangroves of the delta, Sudeep felt safe that tropical South Atlantic morning. Nigerian navy boats were patrolling and the Apecus was moored just outside Bonny, seven nautical miles from land, waiting for permission to enter port.

The warm waters of the Gulf of Guinea, which lap across the coastline of seven West African nations, are the most dangerous in the world. It used to be Somalia, but now this area is the epicentre of modern sea piracy. Of all the seafarers held for ransom globally last year, some 90% were taken here. Sixty-four people were seized from six ships in just the last three months of 2019, according to the International Maritime Bureau, which tracks such incidents. Many more attacks may have gone unreported.![]()

The bountiful oil found here could have made the people of the delta rich, but for most it has been a curse. Spills have poisoned the water and the land, and a fight over the spoils of the industry has fuelled violent crime and conflict for decades. In the villages above the pipelines that have netted billions for the Nigerian government and international oil companies, life expectancy is about 45 years.

Militant groups with comic book names like the Niger Delta Avengers have blown up pipelines and crippled production to demand the redistribution of wealth and resources. Oil thieves siphon off thick black crude and process it in makeshift refineries hidden in the forest. The level of violence in the delta ebbs and flows – but the threat is always there

Sudeep woke up a few hours later to yelling and banging. The watchman in the ship’s command room, high above the deck, had spotted an approaching speedboat carrying nine heavily-armed men. His cry of warning ricocheted around the 80m-long ship as the crew scrambled. They couldn’t stop the pirates, but they could at least try to hide.

Sudeep, just 28 but the ship’s third officer, was in charge of the five other Indian crew working on the Apecus. There was no oil on board, so he knew the pirates would want to take human cargo for ransom. Americans and Europeans are highly prized because their companies pay the highest ransoms but in reality, most sailors come from the developing world. On the Apecus, the Indians were the only non-Africans.

With less than five minutes to act, Sudeep gathered his men in the engine room in the bowels of the ship before running upstairs to set off an emergency alarm that would notify everyone on board. On his way back down, he realised he was only wearing the underwear he had gone to sleep in. Then he caught his first glimpse of the attackers, who were wearing T-shirts and black face coverings, and brandishing assault rifles. They were alongside the vessel, confidently hooking a ladder onto the side.

The Indians decided to hide in a small storeroom, where they crouched among lights, wires and other electrical supplies, and tried to still their panicked breathing. The pirates were soon prowling around outside, their voices echoing above the low hum of engine machinery. The sailors were trembling but stayed silent. Many ships that sail in the Gulf of Guinea invest in safe rooms with bullet-proof walls where crews can take shelter in exactly this kind of situation. The Apecus didn’t have one. The men heard footsteps approaching and the bolt slid open with a clang.

Get up.

The pirates fired at the floor and a bullet fragment struck Sudeep in his left shin, lodging itself just an inch from the bone. The men marched the sailors outside and up onto the deck. They knew they had to move very quickly. The captain had put out a distress call and the gunshots might have been heard by other ships.![]()

The attackers ordered the Indians to climb down a ladder onto the waiting speedboat, which had two engines for extra speed. Chirag, a nervous 22-year-old on his first deployment at sea, was the first to comply. With the pirates’ guns trained on them the others followed, as did the captain.

The six hostages – five Indians and one Nigerian – squatted uncomfortably on the overcrowded boat as it began to motor away. The remaining crew, including one Indian who had managed to evade the attackers, emerged onto the deck. They watched as the pirates sped off towards the delta with their blindfolded captives, leaving the Apecus floating in the tide.

The text message from the shipping agent arrived in the middle of the night.

Dear Sir, understandably Sudeep’s vessel has been hijacked. The Greek owner is co-ordinating the matter. Don’t get panicky. No harm will come to Sudeep. Please keep patience.

Pradeep Choudhury and his wife Suniti, sitting in their bedroom, were left reeling by this perfunctory message. They had spoken to their son just hours earlier. Pradeep began forwarding the text to family members and Sudeep’s closest friends. Could this really be true? Had anyone heard from their son?![]()

Sudeep, as anyone who knows him will say, was mischievous growing up. He was restless, always wanting to get out of the house for an adventure. And his parents, especially his mother, would constantly worry about him. They have lived in Bhubaneswar, a small city in the state of Odisha on India’s eastern coast, for most of Sudeep’s life. It’s a place that Indians living in the centres of power and influence – Delhi, Mumbai or Bangalore – rarely, if ever, think about, but running a small photocopying shop from the front of their home gave the Choudhurys a comfortable life.

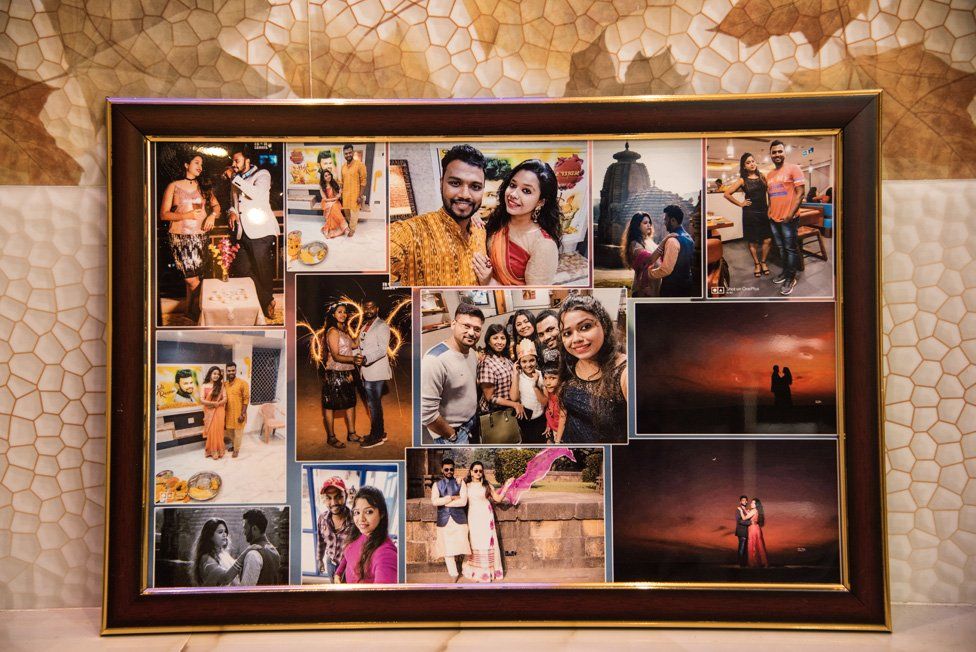

On the busy pavements near their home in central Bhubaneswar, the faces of deities stare out from modest shrines. But before he left for Africa, Sudeep didn’t really believe in any kind of god. Life would be what he and Bhagyashree could make of it. They met when they were teenagers. Now a software engineer, she has the air of a girl who would have been popular at school.

The couple are the kind of aspirational young Indians whose dreams far eclipse the stable, traditional family lives that their parents craved. There are tens of millions like them in India, armed with degrees and certificates but coming of age in a lumbering economy that continues to churns out many more graduates than well-paying jobs.

For Sudeep, a job in merchant shipping promised an escape from all of that. He was lured by stories of good money, plenty of work and a chance to see the world. And he’s not alone – after Filipinos and Indonesians, Indians make up the largest contingent of global seafarers, working as deckhands, cooks, engineers and officers. Some 234,000 of them sailed on foreign-flagged vessels in 2019.

But getting the right qualifications is complicated and Sudeep studied for five years, set on a path that cost his family thousands of dollars. At the age of 27, he finally qualified as a third officer and got a tattoo on his right forearm to celebrate: a little sailing boat bobbing on a cluster of triangles representing the sea, with a large anchor cutting straight through the middle like a dagger.

On the first morning after the sailors were kidnapped, dozens of men emerged from the forest and fired their guns into the sky for nearly half an hour to celebrate. The five Indians, who had been left on a car-sized wooden platform floating on a mangrove swamp, stared hopelessly at the brown water below them.

To get to their jungle prison they had been taken on a snaking, hours-long boat ride through the waterways of the delta. In those first days, the message from the pirates – reinforced with occasional beatings – was clear: if no-one pays a ransom, we will kill you.

Sudeep was still living in his underwear and itched all night under buzzing mosquitoes that left his skin dotted with bites. He hadn’t been given a bandage for the wound on his leg, so he had pushed mud into the hole. The humidity of the jungle meant the men were never dry. They shared a single dirty mat for a bed, and would snatch brief minutes of sleep before jolting awake and remembering where they were.

Early on, the pirates had dragged a skeleton up from the swamp to show the sailors what had supposedly become of a former hostage whose boss had refused to pay. That wasn’t the only macabre threat. On another day, they were shown a pile of concrete blocks. Try anything and we’ll strap these to your legs and drop you in the ocean, the pirates told them.

A rotating cast of guards kept watch from the riverbank, 10 or so metres away. They spent their time fishing, smoking marijuana and drinking a local spirit made from palm sap called kai-kai – but they also watched the hostages closely, occasionally training a gun on them and yelling out a warning, as if their captives might suddenly dive into the murky water and swim away.

Over time, Sudeep would try to strike up a relationship with some of these men. He would gently ask them how they were, or if they had children. But the response was always silence, or a blunt warning. Don’t talk to us. They appeared to be under strict orders but never referred to their leader – who seemed to be based elsewhere in the jungle – by name. He was just “The King”.

Sudeep and the other men – Chirag, 22, Ankit, 21, Avinash, 22, and Moogu, 34 – had little choice but to try to conserve their energy and wait for something to happen. Their lives fell into a kind of lethargic routine. Once a day, normally in mid-morning, they would get a bowl of instant noodles to share between the five of them. They would carefully ration the meal, passing around a grimy spoon and each taking one mouthful. They would repeat the ritual in the evening and hand back the empty bowl.

They were given nothing to drink except muddy water, which was often mixed with petrol. Sometimes they were so thirsty they drank saltwater from the river. The Nigerian captain was kept separately in a hut nearby. He was treated better and the Indians began to loathe him for it.

To pass time, the five men would talk about their lives back home and their plans for the future. They would watch the nature around them – snakes slithering up trees, birds taking flight through the mangroves. They would pray. If the pirates spotted a monkey, the quiet would be broken. The Indians would watch them scramble after it, spraying the animal with bullets. It would later be cooked over a bonfire but the meat was never shared with them.![]()

The sailors tried to keep track of each passing sunset by etching small arrows into the wooden planks that they slept on. They were at times delirious – some of them, including Sudeep, contracted malaria. In whispers, they would imagine a scenario where the pirates came to kill them and they fought back. If they were going to die, they could probably kill at least three of them on the way down, right?

At moments like this they laughed, but it was a constant battle not to sink into despair. During the many quiet hours in which they would simply lie under the beating sun, Sudeep would think over and over what he could do to get them out, and what he would tell the Indian High Commission or his family if he got a chance to call. In his head, he was still trying to plan his wedding.

The pirates’ initial demand was for a ransom of several million dollars. It was an exorbitant sum and one they must have known was unlikely to be paid. But these kinds of ransom kidnappings involve complex and drawn-out negotiations, and in the undiscoverable warrens of the Niger Delta, time always seemed to be on their side.

About 15 days after the attack, the pirates took Sudeep on a boat to another part of the forest, and handed him a satellite phone so he could appeal directly to the ship owner, a Greek businessman based in the Mediterranean port of Piraeus called Captain Christos Traios. His company, Petrogress Inc, operates several oil tankers in West Africa with swashbuckling names like the Optimus and the Invictus.

Sudeep knew little about Capt Christos but had heard he was an aggressive, bad-tempered man. “Sir, this is terrible. We are in a very bad condition. And I need you to act very fast because we might die here,” he told him. His boss, furious about what had happened, was apparently unmoved. The pirates were incensed. “We just want money,” they would say over and over again. “But if your people don’t give us money, we will kill you.”

Their business model is dependent on the compliance of ship bosses who, usually covered by insurance, will pay significant amounts to free their crew after weeks of negotiations. But in this case they were up against a stubborn ship owner. The key now, the kidnappers knew, would be to reach the families.

Back in India, Sudeep’s parents spent their nights lying awake. They knew so little about what had happened that their minds veered towards the worst in those hours before dawn broke, when the streets of Bhubaneswar would briefly be still. They feared their son would never emerge from a pirates’ den that they could scarcely imagine.

There was no way the family could afford to pay the pirates directly and it was never considered as a serious option. The Indian government doesn’t pay ransoms but they hoped it would help them in other ways – by assisting the Nigerian navy to find the pirate camp, or forcing the ship owner to pay up. Bhagyashree and Swapna, a formidable cousin of Sudeep in her mid-30s, took charge of this effort. They corralled the family members of the kidnapped men into a WhatsApp group so they could co-ordinate efforts to get their boys freed.

It soon became clear to Bhagyashree that the pirates would gain nothing by killing the sailors. But she was nervous about how long their patience would last. Pressuring the ship owner from all directions seemed the only feasible way to get her fiancee out. And so in the car, in the bathroom stall at work, and at home lying in bed, she was online, tweeting, firing off pleading emails to anyone who might be able to help.![]()

After three weeks of near-silence, on day 17, the families had a breakthrough. A sister of one of the kidnapped men, Avinash, received a call from her brother in the Nigerian jungle. He told her that all the men were alive but they really needed help. The other families would go on to receive calls from their sons in the coming days – but not Bhagyashree and the Choudhurys.

Strange relationships began to be forged. A relative of one of the sailors who works in the shipping industry, a man called Captain Nasib, began calling the pirates regularly on their satellite phone to check on the men’s condition. But the tinny audio recordings he posted in the WhatsApp chat did not reassure the families. The ship owner “does not care” about the lives of his men and is “playing around”, a pirate angrily told Capt Nasib in one phone call.

On 17 May 2019 – day 28 – the pirates gave Sudeep the chance to speak to Capt Nasib, who assured him that the ordeal would only last a few more days. But Sudeep, as the ranking officer, was told he had to keep everyone’s morale high in the meantime. “I’m trying,” Sudeep can be heard responding in Hindi in a crackly recording of the call. “Tell my family that you talked to me.

Every few weeks the Indians were moved from one jungle lair to another. As negotiations with Capt Christos seemingly broke down, The King himself began to visit them. He would never say much, but the other pirates treated him with a reverence that suggested fear. His status as the group’s leader almost seemed a consequence of his sheer size. All the pirates were muscle-bound and threatening but The King was especially hulking – at least 6ft 6in. He carried a much larger gun than the men under his command, and a leather belt filled with bullets was always strapped around his massive frame.

He would turn up every four or five days and calmly smoke some marijuana before the captives. He would say that Capt Christos was still not playing ball and that this would have consequences. The King spoke deliberately, and with better English than the other men. After many weeks in captivity, the sailors were becoming bony and thin; their eyes were a pale yellow and their urine was at times blood-red. Each visit from the King felt like it brought them closer to the fate of the skeleton they had seen pulled from the mud.

Then events took a more bizarre turn. Up until this point, what had happened to the Apecus seemed to be just another opportunistic ransom kidnapping. But in late May, unbeknown to the men who sat festering on those planks in the swamp, machinations were unfolding that seemed to point to a far more complex series of events.

The Nigerian navy had publicly accused the tanker company of being involved in the transport of stolen crude oil from the Niger Delta to Ghana. The attack on the Apecus and the kidnapping, according to the navy, had actually been provoked by a disagreement between two criminal groups. There had even been arrests. The ship company’s manager in Nigeria had apparently confessed to being involved in illicit oil trading.

Capt Christos, the ship’s owner, fervently denied this. In emails seen by the BBC, he blamed the Indian government for getting the Nigerian navy to detain his vessels and staff in order to force him to “negotiate with terrorists” and pay an “incredible” ransom. Indian authorities dispute this version of events. The Nigerian Navy didn’t comment.

It was a precarious situation for the captives. But the accusations – which put Capt Christos’s tanker operations in Nigeria at risk – did seem to spur him to reach a resolution with the pirates. And so on 13 June, Sudeep’s family finally learned from a government source that negotiations were complete and that payment was being arranged. At the same time, the sailors in the jungle were told that their ordeal might be coming to an end.

The men woke up on the morning of 29 June 2019 like they had almost every day for the previous 70 days. At mid-morning, after handing over the bowl of noodles, one of the guards beckoned Sudeep over and whispered that if things worked out, this could be his last day in the jungle. Two hours later the guard returned with confirmation: the man bringing the money was on his way.

The frail Ghanaian man in his mid-60s who approached in a boat that afternoon, nervously clutching a heavy plastic bag with US dollars peeking out of the top, did not look like a seasoned negotiator. Within minutes of his arrival, it was clear something was not right. A group of pirates began beating the old man. The King, bellowing about the money being short, pulled a small knife out of his belt and stabbed him in the leg, leaving him writhing on the muddy ground. He then approached the Indians and told them that while the Ghanaian would be staying, all six captives were free to go. His men wouldn’t stop them, but if another pirate group picked them up, they were on their own. He looked Sudeep in the eye: “Bye-bye.”

The men did not hesitate. They ran to the water’s edge, where the fishing boat that had brought the bag man was parked. Sudeep told the driver to take them where he had come from. After more than two months he was still in his underwear, though the pirates had given him a torn T-shirt to wear. The boat rocked unsteadily from side to side as it motored away.

After nearly four hours, the driver said he was out of fuel and stopped at a jetty. In the distance, on the outskirts of a small village, a group of barefoot men were playing football. The ragged sailors approached them. When they explained they had been kidnapped, they were ushered into a house and given bottles of water which they gulped down one after the other. Three of the village’s biggest men kept guard outside the guesthouse they were housed in during the night. The Indians, though weak, finally felt safe. “It was as if God himself appointed them as our saviours,” Sudeep said later.

The men were soon in bustling Lagos, waiting for a flight to Mumbai. Alone for the first time in his hotel room, Sudeep poured himself a cold beer, ran a bath and examined his scars. A pirate had inflicted a fresh wound with a fish cleaver on his shoulder a few days before, which stung as he gingerly lowered himself into the steaming bath. An Indian diplomat had given him a packet of cigarettes and over the next hour, he smoked 12 of them one after the other, staring at the ceiling as the water around him slowly cooled.

It’s been eight months since the men were released. Suniti, wearing a yellow sari, sits on the kitchen floor, rolling chapatis on a round block of wood. A few metres away her husband watches the Indian cricket team play New Zealand on TV.

“Sudeeeeeeep!” Suniti calls her son to come downstairs and eat but it sounds like a cry of yearning, as though she’s checking he’s still here. He lost more than 20kg in the 70 days that he spent in the jungle and returned with sunken cheeks. His mother weighed him every few days for the first month, feeling buoyed with each kilo gained.

Bhagyashree passes her mother-in-law a metal plate, her red and gold wedding bangles sliding down her arm as she does so. “I was confident he would return,” she says. “It’s just the start for us, so how can I spend life without him? I believed in the Almighty – that he would come, that he had to come. Nothing can end like this.”

They finally got married in January. The couple have their own space upstairs, but every evening the four of them eat as a family in the small living room on the ground floor. On this night cousin Swapna – who campaigned ferociously for Sudeep’s release – is visiting, and sings a 1960s Bollywood love song after dinner.

Back in his tight-knit family and community, Sudeep appears to have found stability. He is working at the local maritime college, teaching young sailors about safety at sea, although he has put his own ocean-faring days behind him. He shows flashes of joy with his family and friends, but it’s hard to tell what mark months in a pirates’ den has left behind. They rarely talk about it.

“The trauma is still there,” he tells me, as we drive around the dark streets of Bhubaneswar with pop music playing on the car speaker. “But it’s okay. I got married and all my friends and family are here… If I go to the sea then that thing will come again in my mind.”

The ordeal is over but Sudeep and the other men remain tangled in a bureaucratic mess to try to get someone to take responsibility for what happened to them. Since returning, they have not received their salaries, nor any compensation. Sudeep reckons he’s owed close to $10,000 in wages for the more than seven months he spent on the ship and in captivity. Capt Christos did not respond to detailed questions about the kidnapping or whether he disputed that he owed Sudeep money.

He said in an email: “All the kidnapped personnel was safely released and return [sic] to their homes, thanks to Owners ONLY!” The company continues to deny that the Apecus was involved in the purchase of illegal oil, and instead argues it was at Bonny Island for repairs and to pick up supplies. A court case is pending in Nigeria.

What happened to Sudeep underscores the vulnerability of those who find themselves in trouble or exploited at sea – a frontier where regulations and labour protections in theory exist but are difficult to enforce. Seafarers are on the front line of global trade – Nigerian oil ends up at petrol stations across Western Europe, including the UK, as well as India and other parts of Asia. Stories like Sudeep’s, of which there are many, also reflect the human cost of security failings in the Gulf of Guinea. Unlike Somalia, Nigeria – the largest economy in Africa – will not allow international navies to patrol its waters.

After all he’s been through, it seems cruel that Sudeep should need to go through another fight. But he says that he wants to pursue it until the end. “I faced this and that means I can face anything in my life,” he says on another late-night drive. “No-one can break me down mentally. Because for me it’s a second birth, I’m living another life.”

I ask him if it really feels that way. “It’s not feeling that – it is my second life,” he replies. We park outside his house – it’s past 11pm but the lights are still on inside. Bhagyashree and his parents are waiting.

Designed by Manuella Bonomi; Photos by Sanjeet Pattanaik and Getty Images

Credit: Source link