He spotted me on the edge of the dugout and bounded forward with the enthusiasm of a grade-school kid who had just been let out for recess. Michael Jordan, resplendent in his Birmingham Barons pinstripes, didn’t commence with any pleasantries. He got straight to the point — like always.

“Can you believe this s—?” Jordan said to me. “That’s the part of the NBA I don’t miss at all. The drama, the jealousy, the infighting.”

It was May 15, 1994, and two days earlier the Chicago Bulls had eked out an Eastern Conference semifinals playoff win over the New York Knicks. Coach Phil Jackson drew up the final play for Toni Kukoc, opting to utilize Scottie Pippen as the decoy. An incredulous Pippen, who had assumed the mantle as the Bulls’ main attraction post-Jordan retirement, spewed some expletives at Jackson and refused to take the floor. Kukoc nailed a 22-footer at the buzzer, but everyone was still fixated on Pippen.

“Scottie’s getting roasted,” I said to Jordan. “Everyone’s calling him a quitter.”

By then we had shifted to the batting cage. Jordan assumed his hitting stance and began swinging a heavy black bat at a machine spitting a steady stream of baseballs.

“Phil knew how much that would piss Scottie off,” Jordan responded. “I wonder why he did it?”

The 10-part Michael Jordan documentary “The Last Dance” will debut at 9 p.m. ET April 19 on ESPN.

I couldn’t decide which felt more surreal: Michael Jordan asking me about what was going on with the Bulls or witnessing the greatest basketball player who ever lived trying to solve the riddle of the curveball in a minor league baseball park in Birmingham, Alabama.

During his second time around with the Bulls, Jordan was a world-famous icon surrounded by bodyguards, marketing flacks and financial advisers. He had evolved into a brand, and he needed insulation from a relentless public thirsty for any detail, minute or grandiose, about their favorite son. He carefully constructed a wall around himself, impenetrable to most outsiders.

He still graciously made time for longtime journalists who once chatted with him in a batting cage. But the pure, innocent joy of the early triumphs seemed to have evaporated.

The 10-part ESPN documentary “The Last Dance” is a rare inside look inside Jordan’s world. It unfurls some revealing details and telling anecdotes of an emotion-charged final season in which history repeated itself, with the drama, the jealousy and the infighting leading to the disintegration of the Bulls all over again.

In his early years, Jordan could be caustic and held less-gifted teammates to impossibly high standards. And, yet, he was also capable of bringing levity to the team. He loved to talk trash and craved good banter. Once, in the early ’90s, he accosted me the moment I walked into the locker room.

“Jackie,” he barked. “What’s the capital of Mississippi?”

“Jackson,” I quickly replied, suddenly grateful that my husband had a habit of ambushing me with pop quizzes.

“See?” Jordan gestured to Horace Grant. “It’s not that hard! It’s the name of our damn coach!”

By his final season with the Bulls, with the exception of Pippen and Ron Harper, it seemed to me the people Jordan confided in the most were not inside the locker room. He had long maintained a small circle of friends from his native North Carolina, and increasingly sought their counsel. Whenever I dropped into Chicago for a game, Jordan was more likely to be engaged in an animated conversation with security guard Gus Lett than center Luc Longley. Dennis Rodman, a key spoke in the wheel that kept the so-called Last Dance rolling, has told me and many others that he barely spoke to Jordan off the court.

“We didn’t need to be friends,” Rodman said, “for us to win.”

The punctuation of Jordan’s last season in Chicago was his memorable Finals game winner over Bryon Russell. Everyone remembers the shot, but what’s often forgotten is that Jordan swiped the ball free to create that memorable moment, an example of his underrated yet elite defensive instincts. When he nailed the shot over Russell, he exaggerated his follow-through, striking a pose, embracing the flair for the dramatic that we had chronicled for years. Jordan nailed 28 game winners in his career, and, he told me, none of them had been left to chance.

“I believed every time out I was the best,” Jordan explained. “And the more shots I hit, the more it reinforced that. So, when you miss — because no matter how great you are, you will miss — you don’t waver, because you’ve built yourself a nice little cushion of confidence.

“Now, we’ve seen plenty of guys go the other way. They miss one shot and they can’t seem to ever make another one. That’s the kind of negative reinforcement that ruins guys.”

The “Last Dance,” as it turned out, did not signify the end of Jordan’s career. He couldn’t stay away, and when he suited up for the Washington Wizards at age 38, he could no longer seemingly scale tall buildings in a single bound. While his athleticism and skill had faded, his basketball mind was sharper than ever. He routinely met with coach Doug Collins before each game to detail how to best exploit the competition.

Two days after Christmas in 2001, the Wizards were being pummeled by the Pacers in Indianapolis, and Collins pulled Jordan after 25 minutes to rest his cranky knees. What Collins failed to realize was Jordan, who had scored only six points, was in the midst of a streak of 866 consecutive games in double figures, an NBA record at the time.

Collins didn’t find this out until after the game. He later recounted to filmmaker Dan Klores that Jordan plopped down next to Collins on the team bus and asked him if he thought he could still play. Collins assured him he did. In case anyone had doubts, Jordan torched Charlotte for 51 points two nights later, and 45 against the New Jersey Nets two nights after that.

I flew down to Washington unannounced in 2003 to report on Jordan’s final days in the NBA. What I discovered was a man whose knees had betrayed him and who was clearly ready to be done.

“I can go cold turkey,” he assured me. “I’m going to give myself a break and get back to that comfortable 249 pounds I was before.”

He never played again, became an NBA owner, remarried and moved to Florida. We still talk from time to time. He’s mentioned he’s taken up skiing, an activity he enjoyed with his two young daughters. He sounds content.

But, once the subject turns to basketball, that steely resolve returns. Last year, I interviewed him about the mentality of an elite athlete and how they handle pressure.

“People didn’t believe me when I told them I practiced harder than I played, but it was true,” Jordan said. “That’s where my comfort zone was created. By the time the game came, all I had to do was react to what my body was already accustomed to doing.”

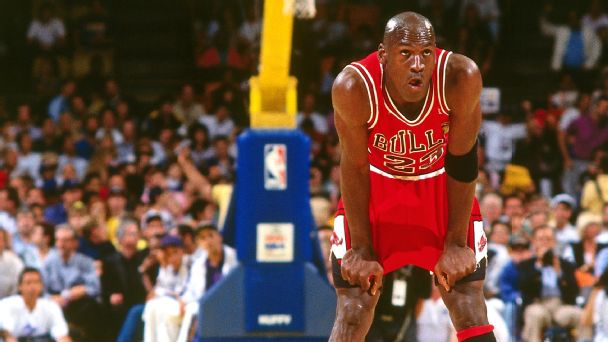

I’ve known Jordan for more than three decades. Much of his coming of age unfolded on the hallowed Boston Garden parquet. “Larry catapulted me from an ‘Ordinary Joe’ to a ‘Somebody Joe,'” Jordan told me of the 63-point playoff performance in 1986 when Bird famously declared, “That’s God as Michael Jordan.” I was there in Richfield, Ohio, for “The Shot” in 1989. I was there for the first title run in 1991 over the Lakers.

And yet, I’m reminded of that time in Birmingham in 1994. Jordan, back to basics, immersing himself in a game that he loved since he was a small child. He knew there were critics who thought he was delusional, self-indulgent. But he didn’t care. He gushed about his teammates who played for pennies instead of millions, whose work ethic rejuvenated and inspired him.

“It’s genuine down here,” he insisted.

Why did he turn his back on the NBA? He was the most dominant player and the most dominant personality, winning title after title. His answer astonished me.

“People got bored with my skills,” he answered, “and what I accomplished was no longer viewed as excellence.”

By 1998, he had certainly recaptured the world’s attention. Twenty-two years later, perhaps we need another refresher on that Michael Jordan.

Credit: Source link