Tokyo (CNN)Everywhere she turned, 8-year-old Haruyo Nihei saw flames.

Bombs dropped by the Americans had created tornadoes of fire so intense that they were sucking mattresses from homes and hurling them down the street along with furniture — and people.

“The flames consumed them, turning them into balls of fire,” says Nihei, now 83.

Nihei had been asleep when the bombs began raining down on Tokyo, then a city comprised of mostly wooden houses, prompting her to flee the home she shared with her parents, her older brother and her younger sister.

As she raced down her street, the superheated winds set her fireproof wrap ablaze. She briefly let go of her father’s hand to toss it off. At that moment, he was swept away into the crush of people trying to escape.

As the flames closed in, Nihei found herself at a Tokyo crossroad, screaming for her father. A stranger wrapped himself around her to protect her from the flames. As more people piled into the intersection, she was pushed to the ground.

As she drifted in and out of consciousness beneath the crush, she remembers hearing muffled voices above: “We are Japanese. We must live. We must live.” Eventually, the voices became weaker. Until silence.

When Nihei was finally pulled out from the pile of people, she saw their bodies charred black. The stranger who had protected her was her father. After falling to the ground, they’d both been shielded from the fire by the charred corpses that were now at their ankles.

It was the early morning of March 10, 1945, and Nihei had just survived the deadliest bombing raid in human history.

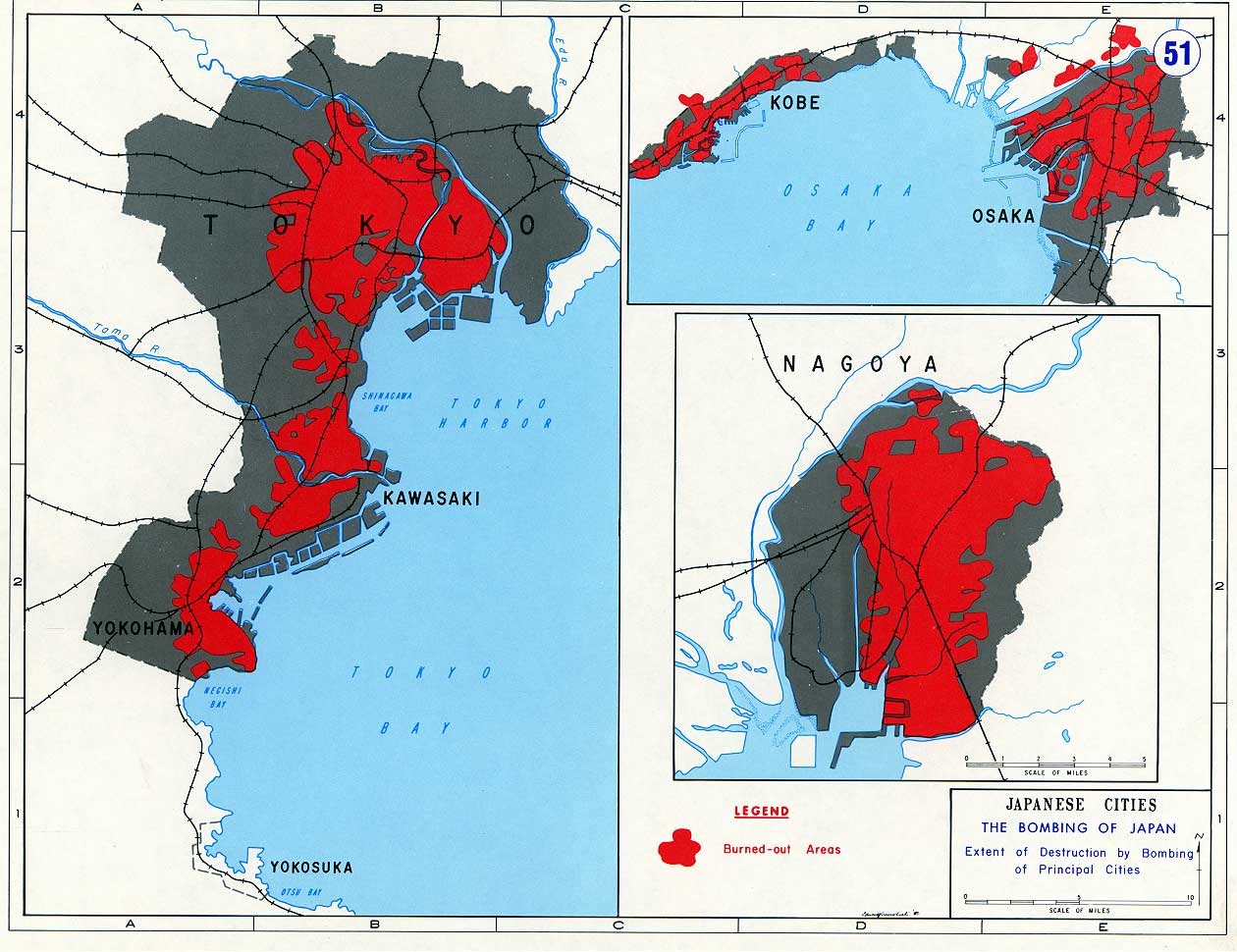

The inferno the bombs created reduced an area of 15.8 square miles to ash. And, by some estimates, a million people were left homeless.

The human toll that night exceeded that of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki later that year, where the initial blasts killed about 70,000 people and 46,000 people respectively, according to the US Department of Energy.

But despite the sheer destruction of the Tokyo air raids, unlike for Hiroshima or Nagasaki, there is no publicly funded museum in Japan’s capital today to officially commemorate March 10. And while the Allied bombing of Dresden in Germany in February 1945 roused a strong public debate on the tactic of unleashing fire on civilian populations, on its 75th anniversary the impact and legacy of the Japan air raids remain largely unknown.

The horrors Nihei saw that night were the result of Operation Meetinghouse, the deadliest of a series of firebombing air raids on Tokyo by the United States Army Air Forces, between February and May 1945.

They were designed largely by Gen. Curtis LeMay, commander of the US bombers in the Pacific. LeMay later launched airstrikes on North Korea and Vietnam and supported the idea of a preemptive nuclear attack against Russia during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962.

Though US President Franklin Roosevelt had sent messages to all warring governments urging them to refrain from the “inhuman barbarism” of bombing civilian populations at the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939, by 1945 that policy had changed.

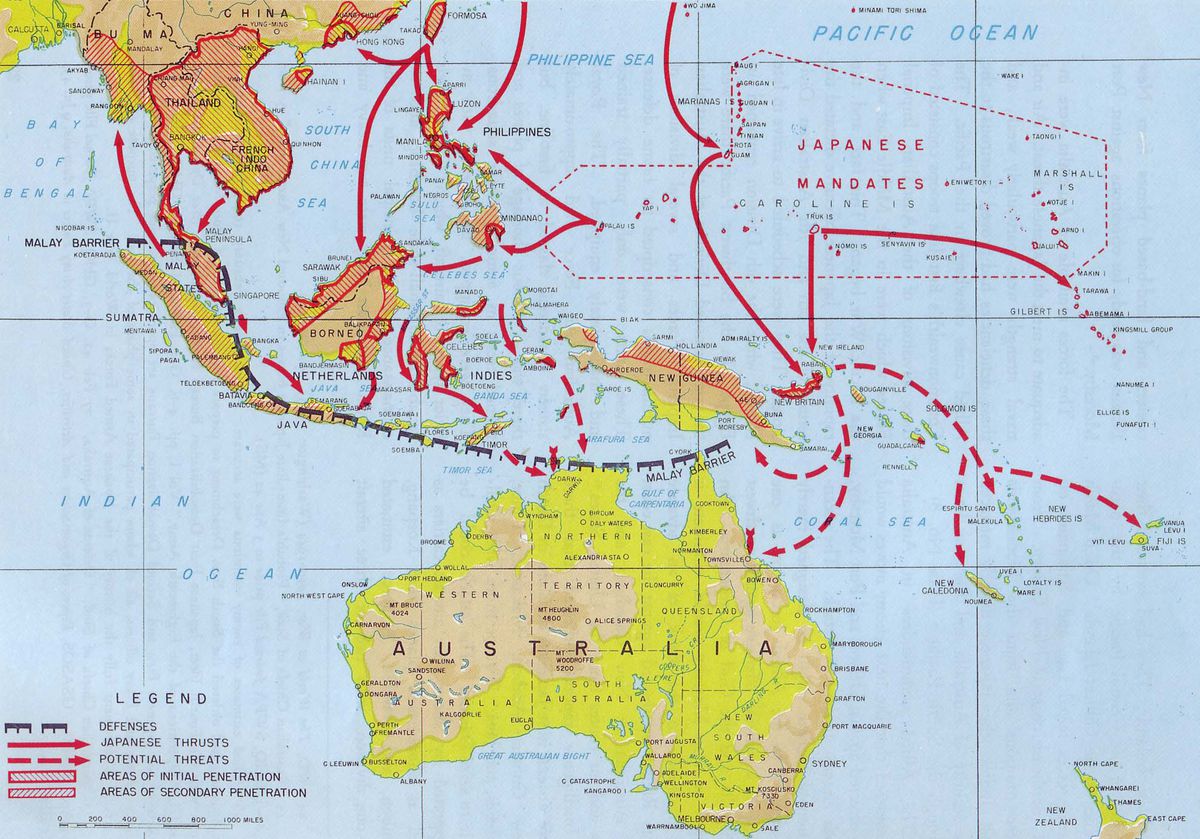

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the US was determined to retaliate. By 1942, Japan’s empire in the Pacific was at its most powerful. US war planners came up with a target list designed to obliterate anything that might help Tokyo, from aircraft bases to ball bearing factories.

But to execute its plan, the US needed air bases in range of Japan’s main islands.

With the invasion of the South Pacific island of Guadalcanal in August 1942, it began to acquire land for that purpose, continuing that mission by picking up the islands of Saipan, Tinian and Guam in 1944.

With that hattrick in hand, the US had territories on which to build airfields for its new, state-of-the-art heavy bomber, the B-29.

Originally conceived to strike Nazi Germany from continental US in the event Britain fell to Hitler’s forces, the B-29 — with its ability to fly fast and high and with large bomb loads — was ideal for taking war to the Japanese homeland, according to Jeremy Kinney, curator at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Virginia.

The bombers were the culmination of 20 years of aviation advances leading up to World War II and were the first to have pressurized, heated fuselages, enabling them to operate above 18,000 feet without crews having to don special gear or use oxygen masks.

That put them out of range of most anti-aircraft guns and gave them plenty of time before fighters could rise up to engage them, Kinney said.

“The B-29 Superfortress was the most advanced technology of its time,” he said.

And US war planners were ready to unleash it on Japan.

But the B-29s’ early attacks on Japan were considered failures.

The planes dropped their explosive loads from the high altitudes — around 30,000 feet — they were designed to operate at, but as few as 20% hit their targets. US crews blamed poor visibility in bad weather and said the strong winds of the jet stream often pushed bombs off target as they fell.

LeMay was tasked with finding a way to get results.

His answer was so drastic it even shocked the crews who would carry out the raids.

The B-29s would go in low — at 5,000 to 8,000 feet. They’d go in at night. And they would go in single file, rather than in the large multi-layered formations the US had used in the daylight bombing of German forces in Europe;

When US air crews were briefed on the mission, many of the more than 3,000 Army aviators reacted with disbelief.

Going in single file, they’d be unable to protect each other from Japanese fighters. And LeMay had ordered the large bombers to be stripped of almost all of their defensive armaments so they could carry more of the fire bombs.

“Most men left the briefing rooms that day convinced of two things: one, LeMay was indeed a maniac; and two, many of them would not live to see the next day,” wrote James Bowman, son of a B-29 fire raid crewman, in a journal compiled from records of the units involved.

Fire from the sky

On the evening of March 9, 1945, on Saipan and Tinian and Guam, the B-29s began leaving their island bases for the seven-hour, 1,500-mile trip to Japan.

Early in the morning of March 10, as the Japanese slept in their low-rise, wooden homes, the first bombers over Tokyo started five sets of marking fires, smaller strikes for the rest of the bomber force to aim it, according to B-29 pilot Robert Bigelow, who recounted the raid for the Virginia Aviation History Project.

Between 1:30 a.m. and 3:00 a.m. the main force of American B-29s unleashed 500,000 M-69 bombs, each one clustered in groups of 38 and weighing six pounds.

The clusters would separate during their descent and small parachutes would carry each bomblet to the ground.

The jellied gasoline — napalm — inside the metal casings would ignite seconds after hitting something solid and shoot the flaming gel onto the surrounding surfaces.

Haruyo Nihei had endured US bombing raids on Tokyo before, but when her father woke her up in the early morning darkness of March 10, he shouted that this one was different.

They needed to get out of the house and to an underground shelter without any delay.

Nihei remembers throwing on the clothes, shoes and emergency rucksack she kept by her pillow and rushing out the house with her mom, younger sister and elder brother. The family, who owned a spice shop, lived in the downtown Tokyo district of Kameido. They rushed passed the local fishmonger’s and small grocery stores that lined the streets.

In those early moments, she remembers not so much the fire, as the air being sucked into the inferno to fuel it. The fire hadn’t reached their district yet.

Her family made it to an underground shelter, but their refuge didn’t last long.

“We were huddled inside — we could hear footsteps overhead fleeing, voices rising, kids screaming ‘mom, mom.’ Parents were screaming their kids’ names,” she said.

Soon, her father told them to get out.

“You’ll be burned alive (in here),” her father said. He thought the flames and smoke would easily overwhelm the bunker door.

But once outside, the horrors were unimaginable. Everything was burning.

The roadway was a river of fire, with homes and their contents, tatami mats, futons, rucksacks, all in flames.

And people. “Babies were burning on the backs of parents. They were running with babies burning on their backs,” Nihei said.

Animals were on fire, too. Nihei recalled a horse pulling a wooden cart loaded with luggage. “It suddenly spread its four legs and froze — then the luggage caught fire — then it caught onto the horse’s tail and consumed the horse,” she said.

The rider refused to leave his mount. “He clung to the horse, and was burned along with the horse,” she said.

In the sky above, the B-29 fliers were feeling the effects of wind and flames.

Bowman, the son of the raid crewman, in his history quotes Jim Wilde, a flight engineer on a B-29.

“Everything below us was fiery red and smoke immediately filled every corner of our plane,” Wilde said.

The hot air rising from the inferno below pushed the 37-ton airplane up 5,000 feet, then dropped it just as quickly seconds later, according to the journal.

B-29 pilot Bigelow recalls the Japanese putting up a defense. “The streams of tracer antiaircraft fire crisscrossed the sky as if sprayed from garden hoses,” Bigelow wrote.

Explosions buffeted his bomber, but the crew focused on their drop.

“We hardly noticed the shrapnel which rattled and tinkled as it rained down on the wings,” he wrote.

Bombs released, Bigelow banked his B-29 sharply and headed out to sea.

“We had created an inferno beyond the wildest imaginings of Dante,” he wrote.

As the B-29 flew more than 150 miles away from Tokyo over the Pacific, Bigelow’s tail gunner radioed the pilot that the glow of the fires was still visible.

‘Killing Japanese didn’t bother me much’

The destruction wrought upon Tokyo on March 10 only emboldened the Americans.

Further fire raids on the Japanese capital on April 14 and 18, and May 24 and 26 reduced a further 38.7 square miles to cinders — an area one-and-a-half times the size of Manhattan.

Tens of thousands more people were killed, and fire bombs followed on the major cities of Nagoya, Osaka and Kobe. The US bombers then targeted “medium-sized towns,” hitting 58 of them, according to the official history.

At one point, the B-29s’ base at North Field, on the tiny island of Tinian, was the busiest airport in the world.

The official US Army Air Force post-war history puts the scope of the fire bomb campaign matter of factly, saying by June Japan’s industrial centers “were finished off as profitable targets.”

But the raids seemed to do little to bring Japan’s capitulation. Some of the damage only enraged its leaders.

“We, the subjects, are enraged at the American acts. I hereby firmly determine with the rest of the 100,000,000 people of this nation to smash the arrogant enemy, whose acts are unpardonable in the eyes of Heaven and men, and thereby to set the Imperial Mind at ease,” then-Prime Minister Suzuki Kantaro said, according to an account by Richard Sams in The Asia Pacific Journal.

Still, the harm inflicted on Japan was massive.

By the end of the campaign, hundreds of thousands of refugees were created across Japan.

LeMay would later acknowledge the sheer brutality of it.

“Killing Japanese didn’t bother me very much at that time… I suppose if I had lost the war, I would have been tried as a war criminal,” he is widely quoted as saying.

Instead, LeMay was hailed as a hero, awarded numerous medals and later promoted to lead the US Strategic Air Command.

“The general built, from the remnants of World War II, an all jet bomber force, manned and supported by professional airmen dedicated to the preservation of peace,” his official Air Force biography reads. He died in 1990 at the age of 84.

When the Emperor spoke

Among the dead Japanese on March 10 were six of Nihei’s close friends. They’d been playing together in the late afternoon of March 9.

“We were playing outside until dusk. We were playing war role play games,” she recalled. “My mom called out that dinner was ready, and we promised we would meet to play again the next day.”

That summer of 1945 was tough for Nihei. She and her family — all of whom survived the March 10 raid — moved from relative to relative, or other temporary accommodation.

Food was short and Nihei found the powdered acorns mixed with water and grains that were available to eat difficult to stomach.

That August, it was announced that, for the first time, Emperor Hirohito would speak directly to the Japanese people. Nihei’s family gathered around a radio to hear his voice.

B-29s had struck devastating blows on Hiroshima and Nagaski, this time using atomic bombs, the only time nuclear weapons had been used in battle.

Hirohito never used the words “surrender” or “defeat” but said “the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb” and Japan would need to accept its enemies’ demands to save the country.

Nihei didn’t care about Japan’s defeat nor did she know much about the new bombs that forced it.

“I didn’t care if we won or lost as long as there were no fire raids — I was 9 years old — it didn’t matter for me either way,” she said.

In a quiet corner of Tokyo’s Koto ward a two-story building that has the air of a residential home in fact houses the Tokyo Air Raids Center for War Damages.

Since a group of air raid survivors bandied together to crowdfund its opening in 2002, it has been preserving their memories and also remembering that Japanese air strikes inflicted severe damage on Chinese civilians in Chongqing, killing 32,000 people between February 1938 and August 1943. And that horrible airstrikes continue to this day in places like Syria and Yemen.

Katsumoto Saotome, the founder of the Tokyo Air Raids Center, had pushed for there to be a government-funded state museum dedicated to the raids. Hopes for this were dashed in 2010, when Tokyo’s municipal government told Saotome there was no public funding available.

Instead, in that year, the Tokyo government began compiling a list of victims. It established a small memorial in the corner of Yokoamicho Park with their names, next to a charnel house with the ashes of Tokyo fire raid victims and those who died in the Great Kanto earthquake of 1923.

But these small gestures of commemoration are not enough for survivors of the air raids.

With over 80% of Japanese born after the war, some fear that younger generations are losing touch with that aspect of the past.

At first, Nihei was too frightened to go alone to the center in 2002, so she asked a friend to come with her.

Once inside, two images took her breath away.

One was a painting depicting charred bodies piled one on top of another.

“It brought back memories of that day, and I really felt like I owed it to all those people who had died to tell others what happened that day,” said Nihei.

The second image portrays the glistening Tokyo skyline. Just above it, children sit on a cloud.

“They reminded me of my best friends, and it made me think they were still having a good time somewhere else.”

Credit: Source link