It used to be pretty simple: put Cristiano Ronaldo in the lineup, win a lot of soccer games. From 2012 through 2018, Ronaldo’s teams won two LaLiga titles, four Champions League trophies, and a European Championship. That’s one major trophy per year — in the age of Lionel Messi’s Barcelona, Pep Guardiola’s Bayern Munich, Vicente Del Bosque’s Spain, Jogi Low’s Germany and Didier Deschamps’s France.

In the word’s truest sense, Ronaldo was the most efficient player in the world; what he did on a soccer field was, arguably, more directly connected to winning trophies than anyone else. Sure, Messi dominated all phases of play, the midfielders behind him dominated the ball, and Guardiola’s various teams dominated the philosophical argument over how best to play the game, but Ronaldo seemed to dominate the decisive moments — with the game in the balance, elimination on the line — in a way that no one else did.

Ronaldo won four of his five Ballons d’Or over that seven-year stretch, an incredible flurry that suddenly, at last, created a conversation over whether he or Messi were the best player of their generation. (Three of Messi’s seven Ballons d’Or came before the 12-18 stint, and two came after.) However, just as suddenly, Ronaldo stopped winning, trophies for himself and his teammates. His last Ballon d’Or came in 2017, and his last major team honor came in 2020 with a Juventus team that had been winning Serie A titles long before he got there. He hasn’t been back to a major final since the 2018 Champions League, and he hasn’t been to the quarterfinals since 2019.

While he used to be the key ingredient to winning, it’s recently started to feel like Ronaldo is the one spoiling the recipe. It’s not just that his teams have stopped winning as he’s aged even deeper into his 30’s; there’s even some evidence that he’s making teams better by leaving and worse by arriving. All the while, the sexual assault allegations against him have infuriated some supporters of the clubs he’s joined, and frustrated plenty of neutral fans, too.

So, with his career winding down and the looming World Cup playoff for Portugal later this week, a last chance for his last chance at the one trophy he hasn’t won, let’s take a look at the Ronaldo effect.

On the field, what does it actually mean when he plays for your team?

The evolution of Cristiano Ronaldo

Let’s start with the player. What does Ronaldo do now, and what did he formerly do?

His peak — better than anyone’s other than Lionel Messi‘s — came for Real Madrid from 2010 through 2015. In domestic play over that stretch, he averaged 31 non-penalty goals per season and 11 assists. Last year, one player in Europe scored 30-plus non-penalty goals in domestic play and 14 registered 11 assists. Ronaldo was basically doing both of those things, every year, for half a decade.

In 2014-15, he scored 38 non-penalty goals and added 16 assists. He scored more goals than Robert Lewandowski ever has in a season, and he was fifth in Europe in assists. Don’t expect to see a season like that again anytime soon.

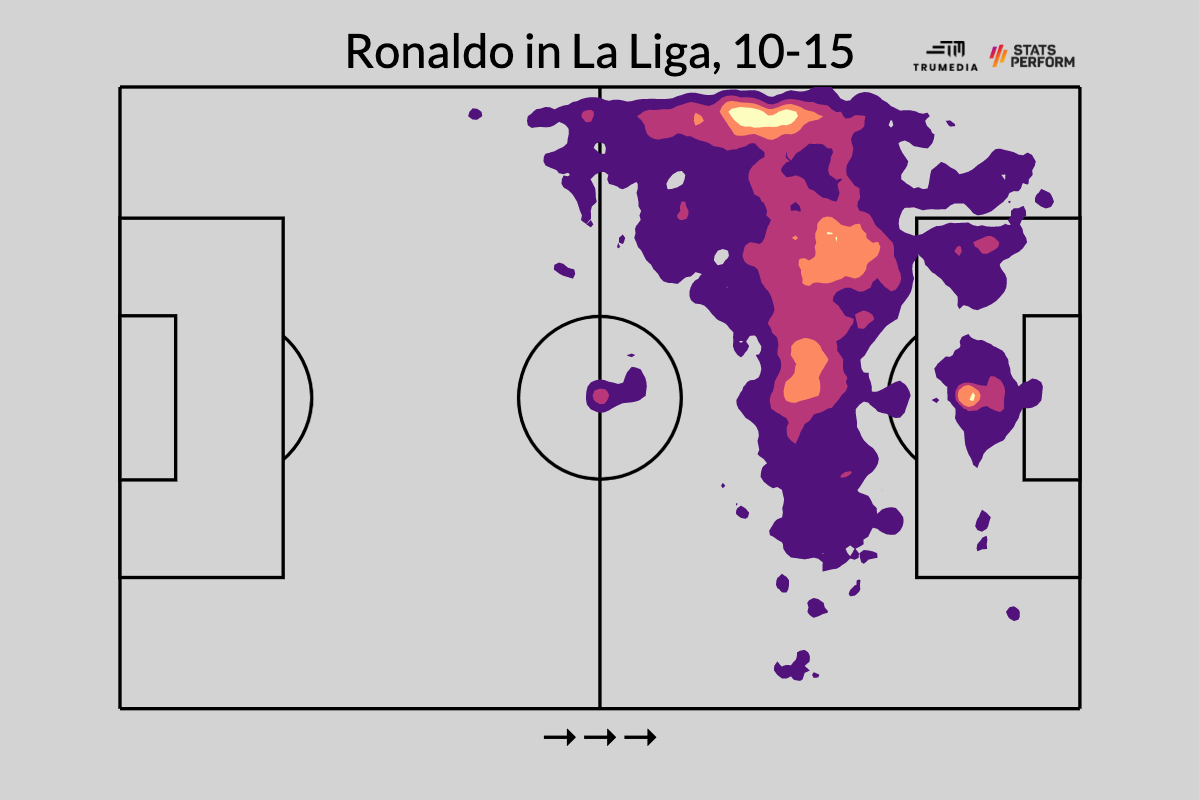

But how was he playing? He was a do-everything, driving, goal-scoring inverted winger — the first of an archetype that has come to define the modern game. Think “a right-footed Salah, but taller and, like, 60% better.” He averaged around 60 touches per match through this stretch and was very involved in buildup play, attempting to both drive the ball forward with his feet and play low-probability passes through crowded areas. He completed fewer than 80% of his passes, played five-ish passes into the penalty area per game, and averaged about eight touches in the box. He also attempted around five take-ons per match and carried the ball at his feet about 34 times.

Most often, Ronaldo was on the ball on the edge of the final third, on the left touchline, but he also had the physical range to constantly enter the most dangerous areas on the field: the left half-space, the central area atop the box and the dead center of the penalty area.

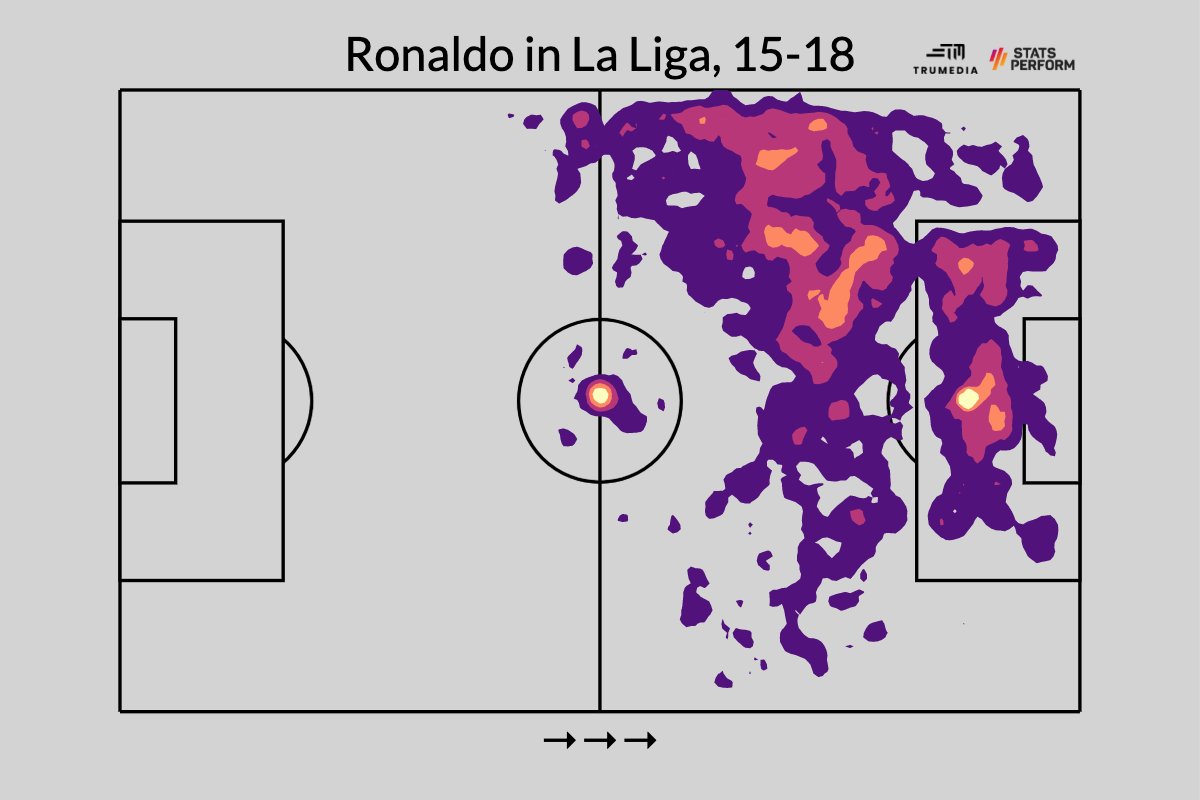

Over the next three years, as Real Madrid won three straight Champions League titles and Ronaldo aged into his 30s, he transformed from a true winger who was scoring like a striker to a striker who was technically starting on the wing. His touches per game dropped all the way down to about 45 per game, his take-ons dropped to about 2.5 per match, he carried the ball 29 times per game, and he played about four passes into the penalty area while completing all of his passes at an 80% clip.

Over the next three years, as Real Madrid won three straight Champions League titles and Ronaldo aged into his 30s, he transformed from a true winger who was scoring like a striker to a striker who was technically starting on the wing. His touches per game dropped all the way down to about 45 per game, his take-ons dropped to about 2.5 per match, he carried the ball 29 times per game, and he played about four passes into the penalty area while completing all of his passes at an 80% clip.

At the same time, his touches inside the penalty area remained relatively stable on average, but his last season with the club (2017-18) saw him record his most touches in the penalty area (10 per match) since 2009. He still scored a ton of goals (24 non-penalty per season), and while he registered 11 assists in 2015-16, he created 11 goals combined in his final two seasons in the Spanish capital.

Over that stretch, the touches on the sideline are gone — and so is the glut of possession at the top of the box. Instead, it’s all shifted into the penalty area.

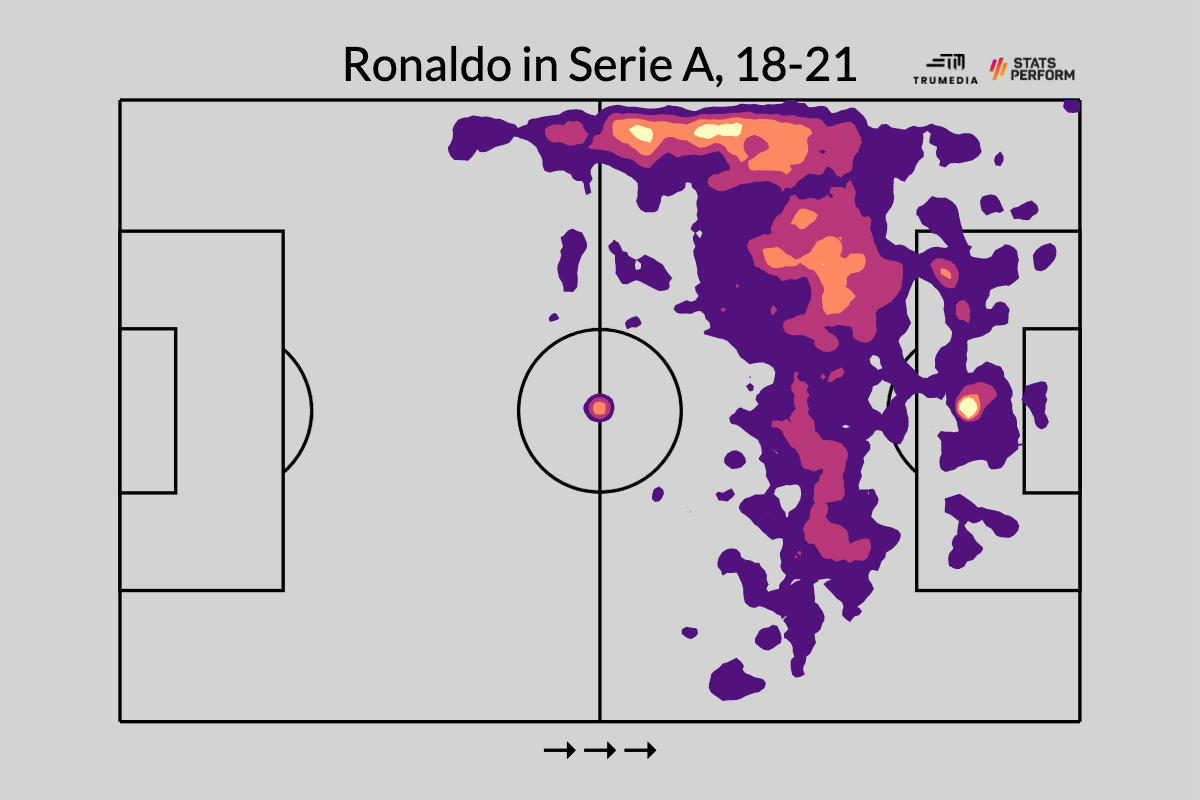

Strangely, once he moved to Italy, Ronaldo started touching the ball a lot more again (54 per game) and carrying the ball a lot more again (35 per game). Except, he no longer had the same range he had when he was younger, and his ball-moving ability wasn’t what it used to be, so you constantly saw Ronaldo, in black and white stripes, receiving the ball somewhere near the midfield line and the opposing team being totally OK with it.

Strangely, once he moved to Italy, Ronaldo started touching the ball a lot more again (54 per game) and carrying the ball a lot more again (35 per game). Except, he no longer had the same range he had when he was younger, and his ball-moving ability wasn’t what it used to be, so you constantly saw Ronaldo, in black and white stripes, receiving the ball somewhere near the midfield line and the opposing team being totally OK with it.

His touches in the box dropped back down to about seven per game, while his pass completion shot up to 84%, as he was on the ball more in areas where safer passing is valued. His passes into the penalty area dropped off to about 3.5 per game, while his assists declined to five per season and his non-penalty goals dipped to 19 per season. He was on the ball more overall, but way less often in the most valuable areas of the field.

Now, at Manchester United at age 37, his touches are back down to 43 per game, he’s attempting the fewest take-ons of his career (1.5), and carrying the ball 23 times per match. He’s pretty much, purely, an off-ball offensive player now: receiving the ball in the box and taking shots. He’s playing just over two passes into the box per game, and although his touches in the box per game are the lowest they’ve been since he first left for Madrid (slightly below seven per game), he still has the eighth-most touches in the penalty area of any player in the Premier League. His assist rate and goal-scoring rate are both the lowest they’ve been since he first left United, too.

Now, at Manchester United at age 37, his touches are back down to 43 per game, he’s attempting the fewest take-ons of his career (1.5), and carrying the ball 23 times per match. He’s pretty much, purely, an off-ball offensive player now: receiving the ball in the box and taking shots. He’s playing just over two passes into the box per game, and although his touches in the box per game are the lowest they’ve been since he first left for Madrid (slightly below seven per game), he still has the eighth-most touches in the penalty area of any player in the Premier League. His assist rate and goal-scoring rate are both the lowest they’ve been since he first left United, too.

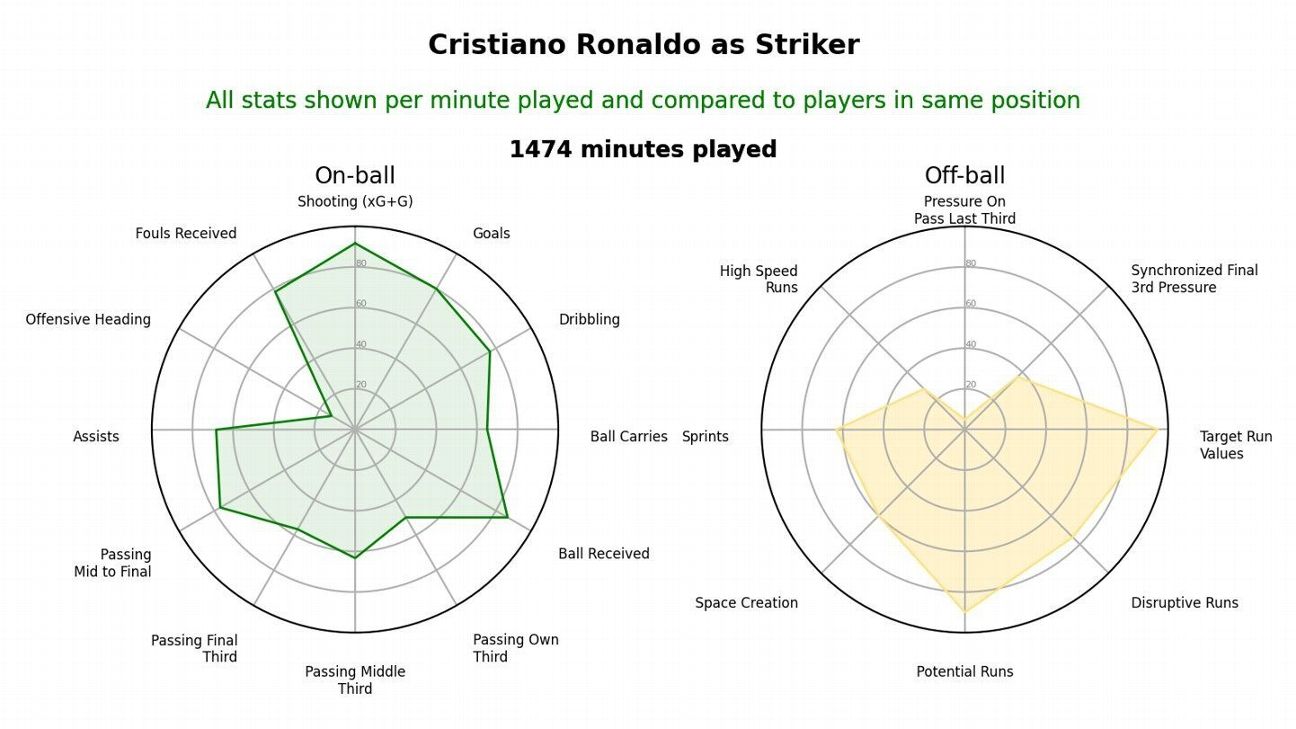

Since his career has spanned various phases of the sport’s fledgling analytics movement, we also have a couple of metrics and measurements today that weren’t available when Ronaldo was at his best. David Sumpter’s team at Twelve Football uses tracking data to create a number of metrics for how players move off the ball and create space. There are sprints and high-speed runs (which are slightly slower than sprints), plus a number of more complex stats:

- target runs: runs when a player receives a pass

- disruptive runs: when a player makes a run but the pass goes elsewhere

- potential runs: when a player makes a run and a pass is attempted to him but isn’t completed

- space creation: the value of a run if a teammate had completed a pass to him

They also look at how involved a player is in pressing. The image on the left shows what Ronaldo is doing on the ball, while the right, which we’re focused on, compiles all the tracking metrics, with each circle representing a percentile ranking:

His pressing barely exists, and over the course of a match, he’s just not running as much as the average Premier League striker. While he has been really efficient with the runs he does make — when he runs, it’s a dangerous run and his teammates pass him the ball — he’s not doing a ton to help open up space for his teammates, as the low space creation and sub-80th-percentile disruptive runs numbers suggest.

His pressing barely exists, and over the course of a match, he’s just not running as much as the average Premier League striker. While he has been really efficient with the runs he does make — when he runs, it’s a dangerous run and his teammates pass him the ball — he’s not doing a ton to help open up space for his teammates, as the low space creation and sub-80th-percentile disruptive runs numbers suggest.

At this stage in his career, Ronaldo makes a couple of great runs per game, turns them into shots and still scores goals … but that’s really about it.

The effect of Ronaldo

It’s impossible to isolate an individual player’s effect on team performance, but it doesn’t mean we can’t try. And we do try, all the time. When we talk about how good or bad a player is, how valuable, we’re talking about how much a given player impacts a given team’s chances of winning compared to other players.

Over the course of a match, a team basically has 11 inputs that all account for a percentage of the number of points a team takes from that match. Over the course of a season, the same is true: The final point total is the output, and each player accounted for some percentage of those points. The trickiest part, among others, is that not all players contribute equally. Robert Lewandowski, say, is worth more points than Benjamin Pavard, but how many more?

Rather than trying to answer that question, let’s just start by ignoring it. That’s what the consultancy Twenty First Group does.

“We instinctively know that the best players feature week-in, week-out for the best teams,” said Omar Chaudhuri, Twenty First Group’s chief intelligence officer. “And anyone not performing is left on the bench.”

While there are occasions when great players are surrounded by average ones, the talent market in soccer tends to push all of the best players toward a select group of teams that can afford to pay the salaries these stars demand. (See: Jack Grealish moving from Aston Villa to Manchester City this past summer, or Luis Diaz‘s recent move from Porto to Liverpool.) It’s obvious, but sometimes it’s easy to forget. The teams that are performing at the highest level are performing at the highest level because the best players in the world are on those teams.

All of the hidden things we can’t measure about this sport show up somewhere in how many games a team wins. If you think a player’s leadership, grit or whatever other intangible you prefer is important, then his teams should win more games because of it.

And over the past five seasons, Ronaldo’s teams really haven’t won that much.

In his final season with Real Madrid, the team won 76 points and finished third in LaLiga, behind Barcelona and Atletico Madrid. In his first season with Juventus, the team won 90 points, five fewer than the season before. The following season, Juventus won 83 — the team’s lowest point total since 2011, when it finished seventh. Then, last year, Juventus took home just 78 points, finishing fourth and ending their nine-year streak atop Serie A.

This season, Manchester United have taken 50 points from 29 games. The projection model from FiveThirtyEight sees them ending the season on 63 points. Last season, they finished with 74. In fact, 63 points would be the lowest total for Manchester United since the Premier League was created.

One of two things is happening here: Either Ronaldo is making the teams he’s joining worse, or he’s maintaining his same level while all of the players on his new teams are suddenly performing at a worse level than before, unrelated to his presence on the field. Given that he’s aging ever deeper into his 30s, the former seems more likely than the latter.

“Ronaldo has been a starter throughout the past five years, so his decline in performance is measured by both his teams failing to hit the heights of previous years, but also his own goal and assist contribution [as a percent of the team’s, so as not to be skewed by the team effects] have also declined,” Chaudhuri said. At Real Madrid from 2010 on, he scored 33% of the team’s non-penalty goals and registered 14% of its assists in domestic play. At Juventus, those numbers dropped to 32% of goals and 11% of assists, and at United they dropped to 28% of goals and 10% of assists.

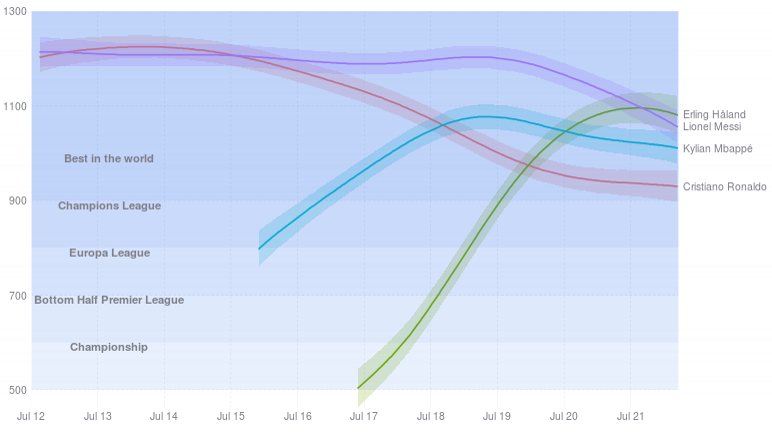

By combining these factors, Twenty First Group creates a rating for each individual player. “Right now Ronaldo sits 64th in the world in our model; for attacking players this puts him just below Bayer Leverkusen‘s Moussa Diaby, but ahead of Atalanta‘s Luis Muriel,” Chaudhuri said. “You can see the decline has been steady, but Ronaldo really began to drop off around the time of his move to Juventus. He’s still very much of a high level, just not quite as good as some of the other superstars.”

For context, Twenty First Group’s current top 10, in order, is: Robert Lewandowski, Erling Haaland, Lionel Messi, Ederson, Mohamed Salah, Thomas Muller, Karim Benzema, Kevin De Bruyne, Joao Cancelo and Kylian Mbappe.

A similar model to Twenty First Group’s was created in 2018 by a group of Carnegie Mellon Ph.D. students. First, they looked at how a team performed when a player was on and off the field, just like the plus-minus rating you might see in the NBA. They then adjusted for the quality of the opponent, but the result was essentially just a list of the best players on the best teams in the world since you were giving everyone equal credit for each point of goal differential. Plus, there are so few subs and so few goals in soccer compared to other sports that you don’t get a constantly churning array of player combinations.

A similar model to Twenty First Group’s was created in 2018 by a group of Carnegie Mellon Ph.D. students. First, they looked at how a team performed when a player was on and off the field, just like the plus-minus rating you might see in the NBA. They then adjusted for the quality of the opponent, but the result was essentially just a list of the best players on the best teams in the world since you were giving everyone equal credit for each point of goal differential. Plus, there are so few subs and so few goals in soccer compared to other sports that you don’t get a constantly churning array of player combinations.

To fix that, they used … FIFA ratings. Yes, from the video game.

Now, before you close your browser and stop reading, the majority of the rating still comes from how a team performs when said player is on the field, and it uses the FIFA rating just as a prior, or as a guide for how much credit a player should get compared to his teammates. Think of the FIFA ratings as crowd-sourced opinions of player quality that cause tiny adjustments in the ratings. If a team is doing terribly although the player on the team still has a good FIFA rating, the system isn’t going to like the player. And to make sure they weren’t inputting faulty data, the researchers found that using the FIFA ratings made the model better at predicting future team performance than if they left them out.

Given that it’s using video game data, though, the model is best used to get a general sense of how much a player helps his team win, rather than an ironclad ranking to directly compare players. Despite Ronaldo’s consistently high FIFA rating, the story is the same one Chaudhuri outlined: His rating has steadily declined as he has ventured beyond Madrid. He has fallen out of the top 10, and since joining Manchester United, he has dropped out of the top 100.

“The reason for Ronaldo’s decline is simple: He didn’t win a lot in Juventus, and Man United are fifth right now in the Premier League,” said Lee Richardson, one of the paper’s authors and now a senior data scientist with Google. “Ronaldo’s impact on winning for these teams was just not high, compared with the players they had previously. The essence of his decline is that his time in Juventus and Man United haven’t been as dominant as his time with Madrid.”

So, um, can Portugal … drop him for World Cup qualifying?

If he’s still scoring goals, then why is Ronaldo potentially making his teams worse? It’s not that he’s suddenly bad at soccer. Of course not!

For one, it’s that rich teams like Juventus and even Manchester United, who let’s not forget finished second in the Premier League last year, theoretically will be improved only by some of the very best players in the world. If you accept the Twenty First Group’s estimate that Ronaldo’s impact is somewhere in the range of the 60th-most valuable player in the world, then that might not be enough to improve teams that were coming off relatively successful seasons before he arrived.

On top of that, Ronaldo is only scoring goals now, and he’s not scoring as much as he used to. While his ability to put the ball into the net still provides value, he’s not providing any value when the team doesn’t have the ball, he’s rarely creating chances for his teammates, and he’s not aiding buildup play much at all.

While that kind of profile still has use for a lot of teams — and even for top teams — if he’s deployed correctly, since he’s Cristiano Ronaldo, he tends to play whenever he wants to play. Most players who can’t run as much as they used to — and simply can’t contribute as much as they used to — just won’t be asked to play as many minutes as they once did. But last season for Juve, at ages 35 and 36, Ronaldo played more domestic minutes than he did in five of his nine seasons with Madrid. Because he’s Ronaldo, his coaches keep playing him more often than they probably should.

With Portugal, it’s not quite the same story. The international game doesn’t really allow for the high-pressing, complex attacking structures that most of the top club teams employ. It’s just a much slower game: The ball doesn’t move as fast, and there just aren’t as many turnovers and transition moments. But despite that, Portugal have suffered roughly the same fate as Ronaldo’s club teams over the past year: They’ve gotten worse. At this time last year, they were fifth in the Elo ratings; now, they’re eighth, thanks to an early elimination at the Euros and the uninspiring World Cup qualifying campaign that pushed them into a win-or-go-home playoff to book a ticket to Qatar this winter.

Just looking at Nations League 2020-21, Euro 2020 and World Cup qualification matches, Ronaldo is averaging about 0.5 non-penalty goals per 90 minutes, 48 touches, five touches in the penalty area, three passes into the penalty area and 28 carries. That’s not too different from what we’ve seen at the club level recently — a little more passing into the box, but fewer touches in the penalty area and fewer non-penalty goals.

According to Twenty First Group’s ratings, there are four Portuguese players currently ahead of Ronaldo: Cancelo, Bernardo Silva (11th), Ruben Dias (13th) and Bruno Fernandes (37th). There’s also Diogo Jota, who is scoring at a higher rate than Ronaldo this season for Liverpool, while also carrying the ball forward more and ranking in the 99th percentile among all forwards in pressures attempted. He has pressured the ball 420 times this season; Ronaldo has done the same just 143 times.

Jota has become close to a pure goal scorer for Liverpool, rather than the kind of facilitating winger who might work best with Ronaldo in his 2021-22 form. Plus, Fernandes and Ronaldo have never quite meshed together, for club (at Man United) or for country.

Since Bernardo Silva usually has one of the wing positions locked up for Portugal, might they function better with Jota playing centrally and a winger like Atletico Madrid’s Joao Felix or AC Milan‘s Rafael Leao on the other side? It feels like a wild statement, but at this point in their careers, Jota is just a better player than Ronaldo.

Put Ronaldo on Liverpool in Jota’s place and the team just wouldn’t be as good; the reverse might be true in Manchester. Among that same spate of matches for Portugal, Jota is scoring more (0.69 non-penalty goals per 90 minutes) than Ronaldo, too. If you started Jota in the playoff, you could also bring Ronaldo off the bench and probably get more efficient production from a limited minute load.

Of course, that scenario is absurd. There’s no way Fernando Santos benches the best player in the country’s history for a decisive pair of matches ahead of what could potentially be Ronaldo’s last World Cup. If you do it and you lose, oh boy — you might not be allowed back into the country. Plus, all those numbers — the ones that say he’s worse than ever before, dragging his teams down with him? They’re all accurate, but they don’t predict the future, either. As Tottenham found out recently, Ronaldo still can take over a game and simply win it all by himself. Those moments are fewer and farther between than they’ve been in 15 or so years, but they haven’t completely disappeared.

The margins in these kinds of games are so thin, so often. Two of Ronaldo’s Champions League trophies came from shootouts, while another required a last-second goal just to force extra time. And Ronaldo’s one major trophy with Portugal came after he was removed in the first half of the Euro 2016 final due to injury. Eder, a player with just five goals for Portugal in his career, scored the winner with a once-in-a-lifetime strike from outside the box.

Against Turkey on March 24 and, if they win that, against Italy or North Macedonia on March 29, Portugal’s margins are going to be thin as ever — a bounce here, a whistle there. One strike, one header could be the difference between a shot at the World Cup or a midseason break in December.

Ronaldo should know that better than anyone.

Credit: Source link