THERE IS NO special treatment at City Kickboxing, not even for the six UFC fighters mixed into this gym of some 350 members training at various levels of competence and interest. Not when two UFC championship belts, belonging to Adesanya and teammate Alexander Volkanovski, lie parallel on a table in the makeshift lobby area of the warehouse that became the gym’s home in November. And not even when there is, like this morning, a photo shoot being orchestrated in one-third of the training area, making plain a contrast the gym’s culture strives to obviate.

Adesanya is beloved by the gym’s members and, maybe most important to him, is treated as an equal. No one ogles or defers to him — he is chided and teased like everyone else. Whenever he finishes working with a gym member, he pulls the person into a tight embrace, reserving, for a few close teammates, an occasional “luhhh you.” City Kickboxing’s membership has more than doubled in the past six months, mostly thanks to the celebrity of Adesanya, now pausing his workout to saunter over to the plain black curtain of a photo set.

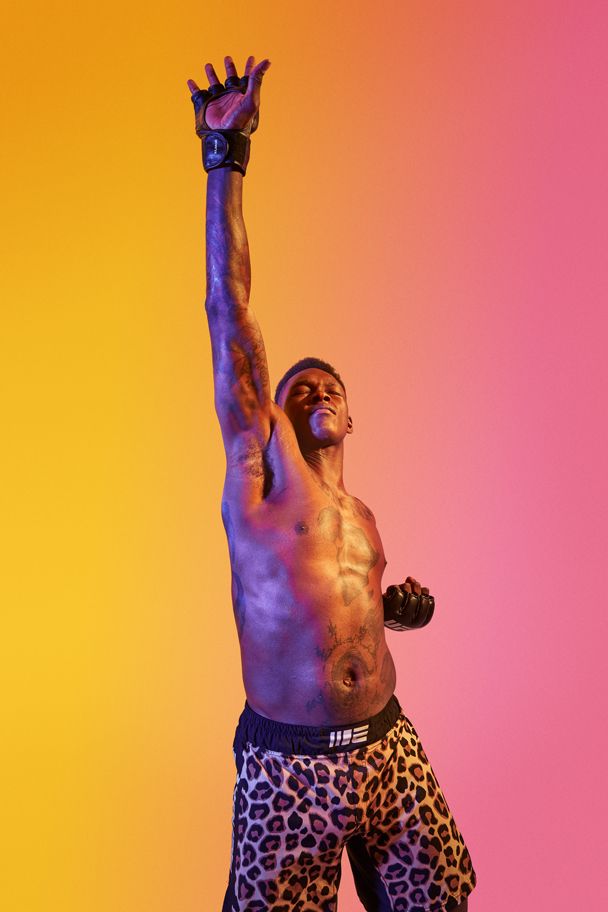

The camera loves Adesanya’s beauty, a long, sloping forehead that descends to the cliff edge of pronounced brows, which drop vertiginously over his eyes — narrow and somewhat feline, with a little fleshiness in the periorbital hollows, scarred tissue — to find the sharp bevel of his cheekbones, which frame a mouth of notable symmetry. When he poses for the camera, he demonstrates — no, performs — a spinning elbow that sends a ribbon of water off his forearm in a perfect arc. The photographer nearly purrs in satisfaction.

“My life is like ‘The Truman Show,'” Adesanya says. “It’s knowing you’re the s— and also knowing that you’re not, that you ain’t s—. I can’t lean into it too much. I have to know I’m just another speck in the sand on the beach of life, you know?” Roger Kisby for ESPN

Head trainer Eugene Bareman did not see any of this coming the first time he met his star pupil. Late in 2009, Adesanya landed an amateur MMA fight via Facebook, and Bareman got roped into cornering him as a favor to a mutual friend. He remembers that the young Adesanya was cocksure. “It was amazing because he had no knowledge of the sport,” Bareman says. “He was fresh off watching a week of YouTube.”

Despite showing signs of talent on his feet, Adesanya was taken down and “mauled,” Bareman recalls. “Thoroughly beaten in every round.”

Bareman thought that was the end of it, but a few months later, Adesanya showed up at his gym asking to train. He tried to brush him off, but the young fighter persisted, and kept showing up, sometimes sleeping in the gym between workouts instead of going home. Even then, Adesanya talked about becoming the UFC middleweight champion.

The two are an odd couple. Bearded and perpetually baseball-capped, the trainer is contemplative, reserved, quietly intense. His student, on the other hand, is a natural showman. “If I didn’t know Israel, [he] would be the last person I would go up and start a conversation with,” Bareman says, laughing. But over time, they developed a tight bond. Today Adesanya calls Bareman a “father figure,” “Yoda,” the “yin to my yang.”

Together they plotted a course toward Adesanya’s lofty goals. He fought for the next several years primarily as a kickboxer, amassing a record of 75-5. In September 2013, Adesanya quit his job as a meter man for a gas company and moved to China so he would have easy access to higher-level opponents and more frequent fights. He sees it now as an ideal training ground for all that was soon to come.

“China was a way for me to fast-track what I knew was going to happen — like being stared at, being mobbed,” he says. “I was a big, black guy in the mainland of China, where they don’t really see foreigners often.” He lived in an austere facility near Zhengzhou with about 70 other fighters. “It was like a prison camp for fighters,” he says. “Steel plates, steel chopsticks. Like a boarding school compound with a gym in the middle.”

He earned the nickname “Black Dragon” from Chinese fight fans, fighting some two dozen times in a span of eight months, sometimes in front of huge crowds. It was one of the loneliest yet most fruitful periods of his life. He didn’t know the language and had little contact with his family, but he kept winning.

I wasn’t meant to fit in. Trying to fit in just never worked at all.

– Israel Adesanya

He returned to Auckland from his self-imposed exile late in the fall of 2014 and launched a hostile takeover of New Zealand’s combat sports scene. That winter, he entered the King in the Ring tournament, an eight-man, single-elimination kickboxing competition in which the victor must win three consecutive matches in one night. Adesanya took the 190-pound title that winter and won the tournament two more times in 2015, defending his crown at 190, then winning the title at 220 pounds six months later. His three wins and 9-0 record in the tournament remain King in the Ring records.

But what made others take notice was how he won. Dan Hennessey, a U.S. Marine-turned-DJ who moved to New Zealand and announces all the King in the Ring matches, speaks of Adesanya in a rapture of hype man’s cant: “He is beautiful violence, a cartoon character come to life. He is like a hawk over the water looking for trout to pluck out of the water. Israel Adesanya is one of a kind.”

Adesanya would christen himself the Last Stylebender, a nod to his love of anime and an apt description of a fighting style that married aggression with a dancer’s instincts for adornment: feinting and potshotting, mugging, raising his arms above his head. He’d kip up after a stumble; he’d awe with occasional capoeira kicks, one part cartwheel, one part head strike; after a knockout, he’d recline on the ropes and turnbuckles, a picture of insouciance; or pirouette like a ballerina in the middle of the ring, just because.

“I’ve always been this entertainer when I fight,” he says. “I make people gasp, laugh, frown. I evoke a lot of emotion out of people.”

He had learned to make a firework display of his self-possession. And he also quietly accumulated a 5-0 record in MMA, never losing sight of where he wanted to go. Early in 2015, he DM’d Dana White on Twitter and told the UFC president that if White put him in the cage, he would do the rest.

Adesanya finally made the move in 2018, debuting at UFC 221 against Rob Wilkinson. Before he stopped Wilkinson in the second round, he mimed raising his leg to pee as he entered the Octagon. After the fight, face unmarked, staring into the television camera, all but winking, Adesanya called out his entire division: “Middleweights! I’m the new dog in the yard, and I just pissed all over this cage.”

Adesanya christened himself the Last Stylebender, a nod to his love of anime and an apt description of a fighting style that married aggression with a dancer’s instincts for adornment. Jean-Yves Lemoigne for ESPN

IN THE SUBURBAN development in Auckland where Adesanya lives, one can hear, in the early morning, a buzz saw screech in the distance and see sprinklers rope trails of water into the air over neighboring lawns, the grass freshly planted and half grown. It is a community still under construction. Inside his home, Adesanya is preparing to head to the gym for his 9 a.m. training. The next day will be the second anniversary of his UFC debut. He hears someone at the door, and he goes to answer it.

A neighbor stands in his doorway and tells Adesanya that a cat has been run over in the street outside his house. He asks whether the cat is his. Adesanya walks outside to discover that it is.

“I was just like, ‘f—,'” he says. “It just made me realize that life is short, man. Life is so short.”

That night, still shaken, Adesanya gets home from dropping off some dinner for a close friend who’s in the hospital and sits in his driveway, alone, for hours, listening to a playlist he hasn’t queued up in a long time. “I created this space in my car, like a time machine,” he says. “I was just in sync. I was just in flow.” Adesanya puts a song (he won’t say which one) on repeat. Over the next several minutes, he uses it to create a new entrance for the Romero fight.

The suddenness of his cat’s death stirs something in him, accelerates a few decisions. He’s not superstitious, but he’s prone to the language of internal struggle, to “epiphanies” and “metamorphoses” and “evolutions.”

“I decided, after my cat got run over, that I don’t want neighbors,” he says. “I’ve always known I wanted a farm, a big piece of land where my nearest neighbor would be 2 kilometers away. That is going to happen even sooner now because of what happened with my cat.”

We are in the back of an Uber, riding under the low-hanging silver matte sky of the early morning, to the southern outskirts of the city, where he has striking practice. He is in a reflective mood, a little tired, less reflexively funny and disarming than he typically is.

I ask what he’s seeking in this distance from others.

“Privacy,” he says. “I like my own space … I just need my own time.”

As much as he yearns for distinction, he’s wary of its cost. “My life is like ‘The Truman Show,'” he says. “Sometimes I feel like a vessel … I’m special. It’s knowing you’re the s— and also knowing that you’re not, that you ain’t s—. Because I can’t lean into it too much and think I’m different from everyone. I still have to know I’m just another speck in the sand on the beach of life, you know? It’s a fine line you walk, and it can send you to some weird places.”

Adesanya is lavishly talented and unusually strong-willed. He has all the ingredients to achieve what he wants, to be one of the greatest mixed martial artists of all time. Which is to say, his stardom could become far more disorienting. He has no use for ordinariness but has a deep need for the ordinary pleasure of privacy. His profession nourishes (unto bursting) the performer in him, the creature who demands Look at me! while threatening to starve the isolato, the bullied art kid who loves anime, the only black boy in class, who must’ve spent a great deal of time living in his own head.

Members of Adesanya’s inner circle marvel at his ability to fulfill his own predictions. He says he visualizes so intensely that he’ll occasionally realize he’s talking to himself as if he were in the scene playing out in his head. Femi calls his son a prophet. Since Adesanya was a teenager, he’s been making lists of things he wants, Tuivoavoa says. After losing every single round of his first amateur MMA fight, he told Bareman that one day he would be the UFC middleweight champion. He said he would beat Robert Whittaker for the middleweight title more than a year before they fought — and, in front of roughly 55,000 people in Melbourne last October, he did.

The Whittaker fight was the culmination of a dominant year. In February, Adesanya dispatched former UFC middleweight champion Anderson Silva in a unanimous decision that was a symbolic passing of the torch, and months later he endured a five-round epic battle against Kelvin Gastelum in what was widely acclaimed as the fight of the year.

Ahead of the Silva fight at UFC 234, Adesanya had asked White for a special walkout. White declined.

“It’s the exact opposite of the mood and the mentality that you’re looking for from a fighter who is just about to fight in the biggest fight of his life,” White says.

But in October, White relented, on the condition that he could see a preview of the walkout before the fight. Adesanya called Tuivoavoa, his childhood friend and former dance crew partner. Together, they cooked up a short, anime-inspired routine during fight week. White saw the rehearsal — and how important the moment was to Adesanya — and agreed to let them go ahead.

Adesanya’s dancing isn’t incidental or a mere promotional quirk — it’s the key to understanding the greatest night of his professional career. In his most important fight, against an opponent who hadn’t lost in more than five years, in front of the UFC’s largest-ever crowd, Adesanya chose to call his shot in the most ostentatious way possible. This was Babe Ruth pointing into the grandstands, Ali predicting the knockout round.

It could have been a disaster. If things had gone wrong in the Octagon, Adesanya’s dance would have become a humiliating meme.

“If you get knocked out, bro, we’re going to look like straight asses,” Tuivoavoa told him. “We’re going to look like so much trash.” But he had learned to stop doubting his friend.

Adesanya had no such doubts himself. “I like that thrill of, ‘Oh, you might win it all, or you might lose it all,'” he says. “I fell asleep the night before [the fight] watching the rehearsal video. I just kept watching it because I was just so excited by the look of it.”

The next morning, Adesanya called his father and told him to go bet on the fight: He was going to knock out Whittaker.

I’ve always been this entertainer when I fight. I make people gasp, laugh, frown. I evoke a lot of emotion out of people.

– Israel Adesanya

Adesanya walked into the Octagon liberated of the pressures of the moment, even as he raised the stakes by choosing the Naruto-inspired dance entrance. “There was no paralysis, overanalysis,” he says. “I wasn’t overanalyzing the fight like Robert was.”

Dancing has made him a natural improviser and a gifted mimic, and his capacity for mimicry allows him to easily home in on his opponent’s rhythm. “I’m really good at copying movement,” he says. “I can see someone do something and replicate it.”

Moreover, he rarely fights in any rhythm himself. He trains off both hands, and he is constantly adjusting and rehearsing — every movement seems to trigger a memory or vision. “That’s what I got this person with,” he’ll say, or “That’s what so-and-so tried to get me with.”

Heading into the fight, Bareman and Adesanya planned to avoid Whittaker’s right hand. But early in the first round, Adesanya noticed that he could time Whittaker’s right, so he started to drift toward it, inviting Whittaker to throw the punch, knowing he could counter. It was a dangerous strategy. Adesanya started exchanging with Whittaker, timing him within a millisecond so he could punch inside of his punches. At the end of the first round, Adesanya leaned away from a looping right hand and countered with his own, dropping Whittaker just as time expired.

A similar exchange ended the fight with about 90 seconds left in the second round. Adesanya ate a Whittaker jab, which sent his head rocking backward. But anticipating Whittaker’s one-two, he had already started his own sequence, a left-hook, right-cross, left-hook combo. The fighters’ first two punches were largely ineffective, but the third — the left hand that Adesanya was throwing all along and that Whittaker could not catch up with — caught him clean and sent him down like a marionette severed from its strings. A few seconds later, the fight was over.

Adesanya was the new undisputed middleweight champion.

Credit: Source link