A recent ruling by the Court of Appeal on construction of the standard gauge railway (SGR) has once again brought to the fore a matter that has refused to go away — when to admit evidence that has been obtained without the consent of an opposing party.

In the case, Kenya Railways Corporation successfully argued for a number of documents, which it said were obtained in a clandestine manner by activist Okiya Omtatah, to be expunged from the court record.

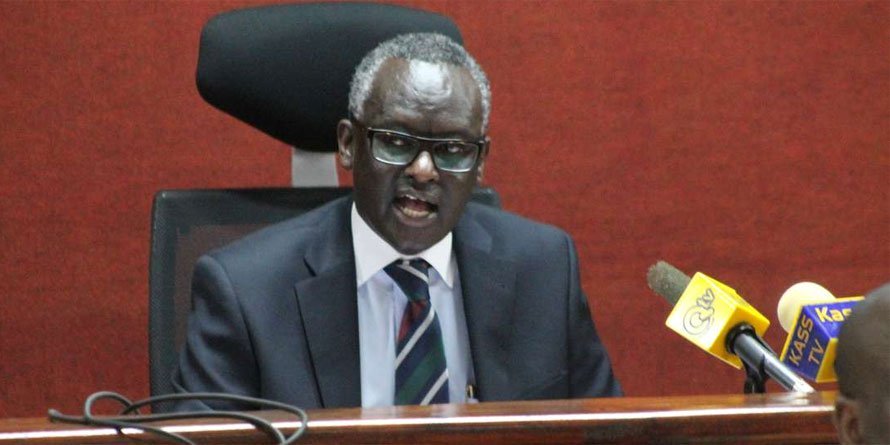

In 2015, Justice Isaac Lenaola (now a judge of the Supreme Court) expunged the documents submitted by Mr Omtatah and the Law Society of Kenya (LSK) after KRC questioned how they obtained the confidential documents on the SGR deal.

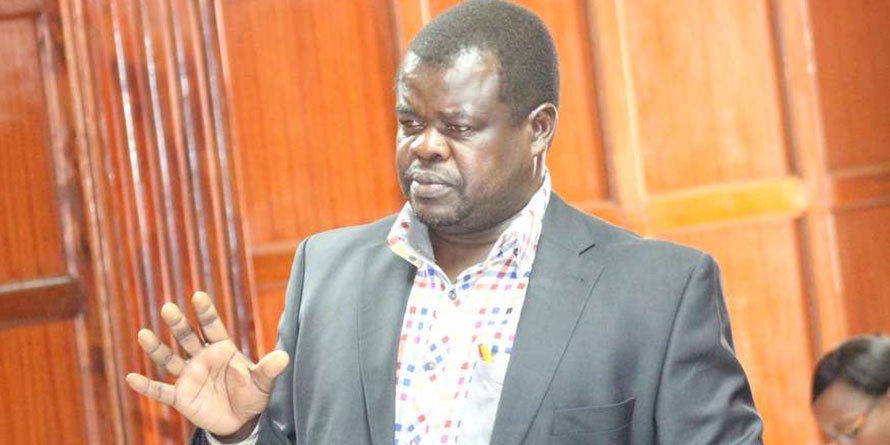

Mr Omtatah wanted to show, using the documents, that single sourcing of project was a violation of the law. He argued that there was no open tendering and the conditions for direct procurement under Section 74 of the Public Procurement Act were not met.

The activist further argued that the government did not put in place measures to ensure value for money in undertaking the project and that the state failed to consider the financial capacity of China Road & Bridge Corporation (CRBC) and also guard against conflict of interest.

In the appeal, a bench of three judges upheld Justice Lenaola’s decision saying, “However well intentioned “conscientious citizens” or “whistle-blowers” might be in checking public officers, there can be no justification, as pointed out by the Supreme Court, for not following proper procedures in the procurement of evidence. We do not have any basis for interfering with the decision of the High Court to expunge the documents in question.”

The documents in question included copies of numerous letters exchanged between the Ministry of Transport and the Chinese company, correspondence between CRBC and the then Prime Minister’s office, memorandum of understanding between Ministry of Transport and CRBC dated August 12, 2009, correspondence between the Chinese Embassy and the Ministry and correspondence between the Office of the then Deputy Prime Minister and the Chinese Ambassador.

Other documents were the feasibility study relating to the project, correspondence between the ministry and KRC, correspondence between the Attorney-General’s office and the ministry, between KRC and Public Procurement and Oversight Authority, the commercial contracts between the KRC and CRBC for the construction of the railway and cabinet memorandum on the project.

In the appeal, Mr Omtatah argued that in addition to failing to heed Article 35 of the Constitution which recognises that every citizen has the right of access to information held by the State, Justice Lenaola failed to appreciate that the documents had been tabled before Parliamentary Committees, which was investigating the project.

He maintained that the documents were not confidential as alleged and, it was wrong for the judge to expunge them together with a report from Parliament on the SGR, from the court records.

On its part, LSK through Apollo Mboya said all the documents that the society relied on, were lawfully obtained. He said they were submitted to the LSK “by conscientious citizens in lawful possession of the said documents.”

Further, LSK argued that KRC had not shown that the documents were false or called the makers to denounce them. Mr Mboya said citizens have rights of access to information under Article 35 of the Constitution and all State organs are enjoined to be transparent and accountable and expunging the documents was a smoke screen to distract the court from addressing the real controversy.

In a famously quoted decision in the court corridors on the admissibility of evidence, (Reg. vs Leatham), Justice Crompton said “it matters not how you get it if you steal it even, it would be admissible in evidence.”

The Constitution, however, shifted the paradigm and Article 50(4) now disallows such evidence.

The said Article states, “Evidence obtained in a manner that violates any right or fundamental freedom in the Bill of Rights shall be excluded if the admission of that evidence would render the trial unfair, or would otherwise be detrimental to the administration of justice…”

KRC argued that a constitutional petition cannot be founded on alleged “public documents” obtained in breach of the Constitution and the Evidence Act.

The agency questioned the source or origin of the documents because it had not been disclosed and its authenticity cannot therefore be vouched for.

In the judgement, Justice Lenaola had said if litigants choose to use clandestine means to procure information, such actions would heavily compromise the need for Article 35 of the Constitution and violate the other parties’ fundamental right to privacy under Article 31 of the Constitution.

The judge went on to say that the procedure for introducing public documents into court as evidence under Section 80 of the Evidence Act guarantees the authenticity and integrity of documents relied upon in the court but the documents tabled by Mr Omtatah and LSK did not meet the criteria of admissibility.

In the appeal, the corporation maintained that Justice Lenaola correctly allowed the removal of the documents that had been obtained in a clandestine manner.

Through Prof Albert Mumma, KRC cited the commercial contracts, letters exchanged between government officers and diplomatic missions, a draft Cabinet memorandum, which he said were all not public.

The lawyer said whereas Article 35 of the Constitution gives every citizen a right to access information held by the State, it does not permit “self-help” for citizens to obtain official documents from public officers clandestinely.

In a different ruling in December 2017, the Supreme Court expunged from the court record some documents submitted by Mr Njonjo Mue and Mr Khelef Khalifa. The documents were mostly internal memos sent by the then Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission chief executive officer Ezra Chiloba. They had been filed to support a presidential election petition.

In the ruling, the six judges of the court led by Chief Justice David Maraga said a duty had been imposed upon the citizen(s) to follow the prescribed procedure whenever they require access to any such information.

“This duty cannot be abrogated or derogated from, as any such derogation would lead to a breach and or violation of the fundamental principles of freedom of access to information provided under the Constitution and the constituting provisions of the law,” the court said.

But in a different case in 2018, Employment and Labour relations judge Hellen Wasilwa said “in Kenya, illegally obtained evidence is admissible so long as it is relevant to the fact in issue or its admission would not affect the fairness of the trial.”

The judge made the decision in a case filed by employees of Mater Hospital, among them doctors to prove their case. She said such evidence, among them copies of minutes from a crisis meeting, were relevant.

The judge ruled, “In determining whether to allow evidence being sought to be expunged, I am guided by the fact that the primary duty of this court is to do justice.”

She added that if justice will be done using available documents and evidence not obtained in breach of the Constitution and the law, then the court would admit such evidence in order to have the right resources before it to enable determination of the issues in a just matter.

In yet another case involving United Airlines vs Kenya Commercial Bank (KCB), the Court of Appeal allowed a controversial document to be used saying it was clear from the face of the document that it was not communication between a lawyer and a client as alleged.

“It is communication within the legal department of the respondent and not to any specifically named individual,” the judges said.

The court went on to state that the communication was not privileged or confidential information that should be protected under the guise of confidentiality.

“Moreover, the person who sought to produce the document was its author, and the information was not being disclosed to a stranger third party but to the subject of the memo,” the judges said, adding that “If anything, under Article 35(1)(b) of the Constitution, the appellant had a right to the said information to enable him prosecute his case fairly.”

Credit: Source link