Historian Susan Williams grew up in Zambia. Like other scholars of her generation raised in former settler societies of southern Africa, she empathises with the continent’s people.

Williams’ widely acknowledged new book, White Malice – The CIA and the Neocolonisation of Africa, adds to her track record, testifying to this engagement. Almost a forensic account, its more than 500 pages (supported by close to 150 pages of sources, references and index) are as readable as a John le Carré novel.

But make no mistake: Williams ruthlessly reveals through factual evidence the unsavoury machinations of the American Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in Africa during the Cold War until the late 1960s. While scholarly analyses of this era have increased, the literature mainly focuses on how geostrategic aspects had an impact on international policy. In contrast, this is the first detailed account disclosing a Western dirty war through detailed quotes from original documents and by those involved.

Published in 2011, her investigative research titled Who Killed Hammarskjöld? The UN, the Cold War and White Supremacy in Africa made history. The evidence strengthened suspicions that the plane crash that killed the United Nations Secretary General and 15 others on 17/18 September 1961 near Ndola, in then Northern Rhodesia, was no accident. As continuously updated by the Westminster branch of the United Nations Association, the disclosures triggered new investigations by the UN.

In 2016 Williams published Spies in the Congo: The Race for the Ore that Built the Atomic Bomb. The focus was on Shinkolobwe, the world’s biggest uranium mine, in the Congolese Katanga province. Of crucial geostrategic importance, in the 1940s it supplied the Manhattan Project, which produced the first atomic bombs, which devastated Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Shinkolobwe remained the main resource in the American nuclear arming of the 1950s.

White Malice

Williams’ new book seems like the third in a trilogy. Its title, White Malice, captures the racist arrogance of power, unscrupulously destabilising and (re-)gaining control over sovereign states as a form of colonialism by other means.

Not by coincidence, the book revisits the circumstances of Hammarskjöld’s death and the relevance of Katanga. More room is devoted to a step-by-step account leading to the elimination of Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of an independent Congo.

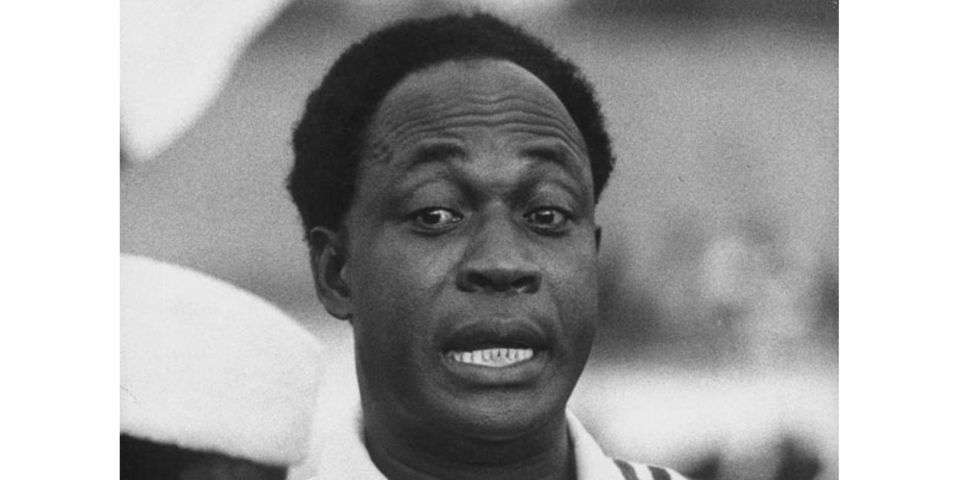

Another major focus is on Ghana since independence in 1957. Documenting the continental role of President Kwame Nkrumah, it explains why and how he was removed from office. His role in promoting pan-Africanism was equated with an anti-Western attitude.

All this is tied together by the interventions by the CIA and its predecessor, the Office for Strategic Services, often in cahoots with the British MI6. The detailed accounts offer insights into the secret operations then. The display of mindsets and their consequences do not require theory or analytical comment. The facts speak for themselves.

Both agencies shared access to the encrypted messages used in confidential communication by Hammarskjöld and other high-ranking UN officials. As quoted by Williams (p. 290), the CIA celebrated this as “the intelligence coup of the century”.

The UK and the USA have still not disclosed insider knowledge concerning the deaths of Hammarskjöld and his entourage. Their secret agents were also involved in deliberations to kill Lumumba. Though they weren’t directly participating in his abduction, torture and execution in Katanga, it suited their agenda.

Nkrumah was luckier. A state visit to Beijing saved his life, when in his absence the military coup took place. Nelson Mandela was also “spared” by being imprisoned for most of the next 30 years. His arrest in South Africa in 1962 under the Suppression of Communism Act was based on information provided by the CIA (p. 474).

Western mindset

Williams quotes (p. 77) a high-ranking CIA agent to illustrate the overall Western mindset. He declared in 1957:

“Africa has become the real battleground and the next field of the big test of strength – not only for the free world and the communist world but for our own country and our Allies who are colonialist powers.”

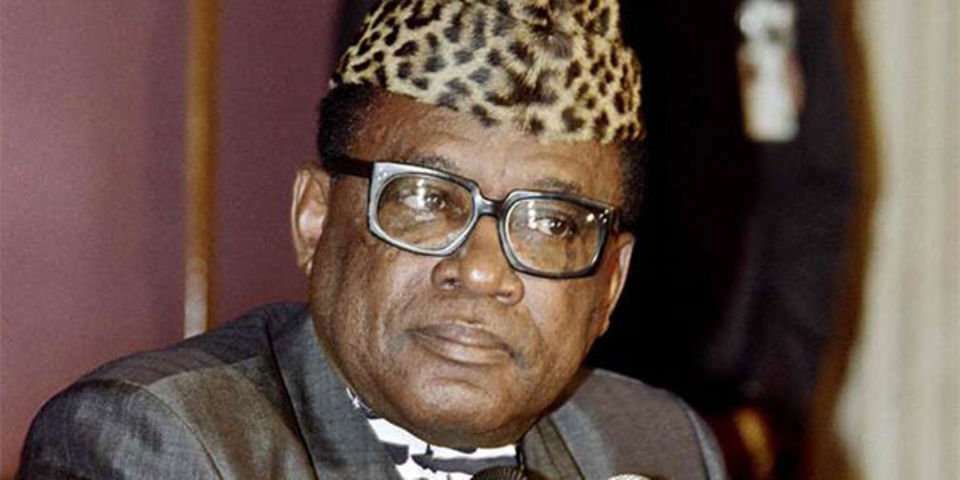

The strategy included replacing independent nationalist leaders with “big men” – autocrats who based their power on Western support, such as Mobutu Sese Seko. A track record in or commitment to democracy and human rights was not a prerequisite.

In contrast, leaders like Guinea’s Sékou Touré were considered enemies. Arguing for a referendum rejecting continued dependency from France, he declared in 1958:

Guinea prefers poverty in freedom to riches in slavery (p. 74).

Cultural operations

CIA operations were not confined to plots ending in brute force. Some were cultural programmes, unbeknown to many artists and scholars who received CIA sponsorship.

This included stipends to South African writers in exile, such as Es’kia Mphahlele and Nat Nakasa, as well as the sponsoring of cultural festivals and conferences in Africa. Williams (p. 64) quotes the future Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka, who after discovering that he had unknowingly received CIA funds declared:

“We had been dining, and with relish, with the original of that serpentine incarnation, the Devil himself, romping in our post-colonial Garden of Eden and gorging on the fruits of the Tree of Knowledge.”

In a spectacular disclosure (pp. 324-331) Williams presents details of CIA-funded concerts by Louis Armstrong, touring 27 African cities in 11 weeks during late 1960. This included a concert in Elisabethville, the Katanga breakaway province of Congo, at a time when Lumumba’s end was near. According to Williams:

“Armstrong was basically a Trojan horse for the CIA … He would have been horrified.”

Facts, not fiction

The US’s obsessive anti-communism, which escalated in the era of Senator Joseph McCarthy, at times took lethal forms when governments or leaders were considered to be obstructing Western interests.

A sense of guilt or remorse remains absent. Mike Pompeo says it all. Then CIA director from January 2017 to April 2018 and Donald Trump’s Secretary of State, “celebrated immorality”, as Williams drily comments (p. 515). “I was the CIA director,” Pompeo boosted in a quoted speech in 2019:

We lied, we cheated, we stole. We had entire training courses. It reminds you of the glory of the American experiment.

The story, unlike John le Carré’s, is definitely not fiction. CIA operations, at times in collaboration with other Western intelligence agencies, were pursuing a hegemonic agenda with lasting impact.

Credit: Source link