After the World Cup, it was the same answer it’s always been: Lionel Messi. The seven-time Ballon d’Or winner was the best player in Qatar, and he led Argentina to the only major trophy that was missing from his already sterling résumé. Who is the best player in the world? At age 35, Messi completed the sport, and in a way that no other living soccer player seemed capable of doing.

But, well, did you watch the Bayern games in the Champions League? Paris Saint-Germain scored a whopping zero goals across two matches, and nothing from them suggested that Messi was still the best soccer player in the world.

How ’bout the guy he beat in the World Cup final, the next-if-not-already-best player in the world, Kylian Mbappe? Well, he too didn’t do all that much in the second leg in Germany, either: just 30 touches, fewer than any other player who was out there for at least 70 minutes. Neither Messi nor Mbappe — in their 90 most important minutes of the season — seemed like players capable of taking over a game, regardless of their teammates, their tactics, or their opponents.

As the constantly shifting context I just applied in the previous paragraph suggests, it’s really hard to confidently say who the “best” soccer player in the world is — unless that player is the best scorer, creator, dribbler and passer all at the same time, as Messi was for most of his career. It also doesn’t really matter. This isn’t basketball, a five-person game on a tiny court where having the best player is automatically a leg up. In an 11-person game on a large field with very few scoring chances, having the best player is more a bit of trivia than overwhelming strategic advantage.

That doesn’t mean it isn’t fun to think about, though. And with Mbappe and Messi limping out of the Champions League round of 16 for the second year in a row — and doing it together — it feels like all kinds of different players could make a reasonable claim to being the best player in the world for the 2022-23. It all depends on how you want to look at it.

Goals

We’ll start here. All the other stuff that happens on the field is cool and all — last-ditch tackles, savvy feints through pressure, raking diagonals, passes only the passer could see — but it pales in comparison to the ability to consistently put the ball into the back of the net. If you’re able to score more goals than anyone else on the planet, you automatically have a claim to being the best soccer player in the world.

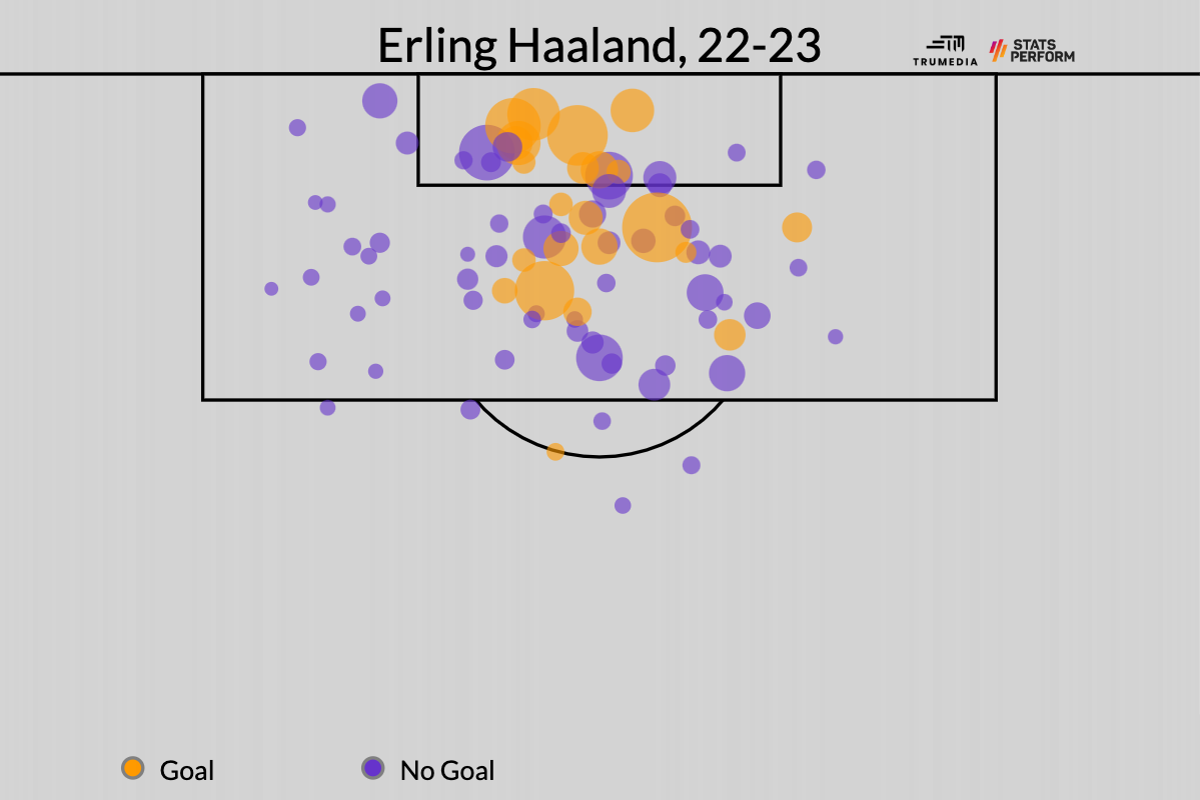

This season, no one has scored more goals than Manchester City‘s Erling Haaland. Through 26 Premier League appearances, he already has 28 goals. That’s perhaps a bit inflated by his five penalties, but if we strip penalties out, he’s still ahead of everyone else with 23. In fact, if you took away Haaland’s penalties but let everyone else keep theirs, the 22-year-old Norwegian behemoth would still have three more goals than anyone else.

The circles are sized by the quality of the chances:

In terms of non-penalty goals, Napoli‘s Victor Osimhen (19) starts to close the gap. He’s also made four fewer appearances, so on a per-90 basis, it’s even closer between the Nigerian (0.93) and the Norwegian (0.98) in terms of expected goals. Drill down to non-penalty expected goals per 90 minutes, and both Osimhen (0.74) and Barcelona‘s Robert Lewandowski (0.73) are ahead of Haaland’s 0.70. But we shouldn’t penalize Haaland for playing more minutes than both of them — availability is an ability! — and he’s still generated more total xG (16.43) than any other player. Plus, we’re now on year four of Haaland scoring significantly more goals than expected.

In other words, Haaland has both been better at finding space in the most valuable area of the field and better at converting all of the chances that his elite off-ball movement allows him to occupy.

What about passing?

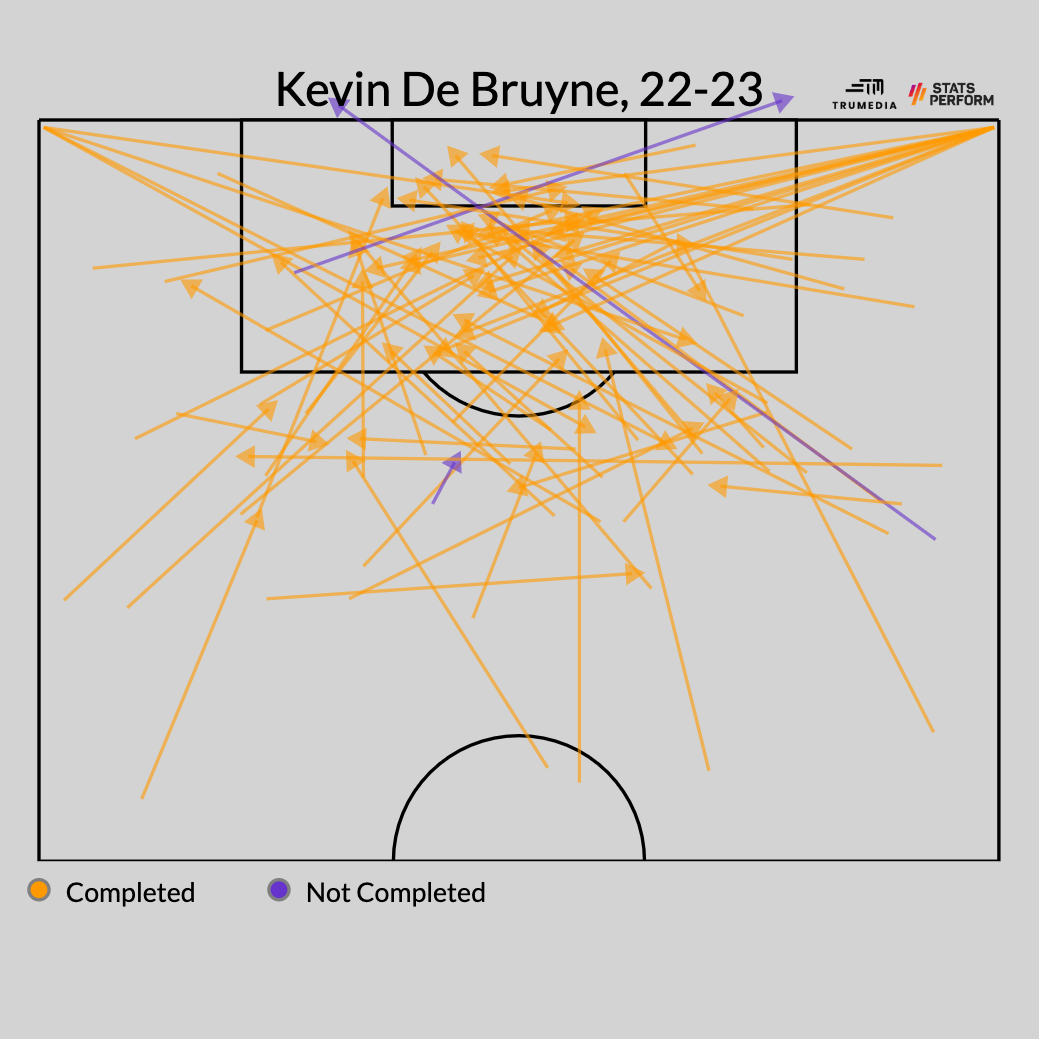

If we accept that goal scoring is the most important individual ability in the sport, then the second-biggest contribution would be playing the pass that creates the opportunity to shoot the ball at the goal.

We could measure that by looking at assists, but assists are in large part influenced by another player’s ability to convert the pass into a goal. So, instead, we’ll look at expected assists, which values every pass by the likelihood that it’ll be converted into a goal.

Only two players in Europe have created more than eight expected assists so far this season: Messi (10.84) and Haaland’s teammate Kevin De Bruyne (11.43). Here are all the chances the latter has created this season:

However, only four players have 10 or more assists this season, while 47 players have at least 10 goals. Individual goal-scoring has a larger effect on matches than individual creativity.

What if we add up non-penalty goals with the number of expected assists? That should give us a better picture of attacking influence, and it shows four players with a number north of 20:

- 4. Victor Osimhen, Napoli: 20.23

- 3. Kylian Mbappe, PSG: 22.87

- 2. Lionel Messi, PSG: 23.84

- 1. Erling Haaland, Man City: 25.58

Given PSG’s massive financial advantage over their Ligue 1 opponents, those Messi and Mbappe numbers are less impressive than what either Osimhen or Haaland have done so far. From a purely attacking-the-goal perspective, Haaland and Osimhen have been the two best players in the world so far this season. Reports of the death of the striker have been greatly exaggerated.

And how about, uh, everything else?

Of course, how many goals you score and create doesn’t really come close to providing a comprehensive summary of how good of a player you are. In terms of “good”-ness, what we’re really looking for is how much you contribute to winning. We could value it in points or, to slightly simplify it, you could say we’re looking for what your overall contribution to your team’s goal differential is.

For example, Arsenal have a plus-37 goal differential through 27 matches. Twenty-three different players have played at least 20 minutes for Mikel Arteta so far this season, and they’ve all contributed — positively or negatively, massively or fractionally — to that goal differential.

Now, we don’t have a good way of parceling that all out. Everything that happens on the field contributes to a team’s overall performance, and we’ll never be able to perfectly quantify the value of each thing, on and off the ball, that a given player does. Still, if we’re searching for the best player — the player who has contributed the most to winning so far this season — then we could do worse than looking at the players who have been on the field the most for the teams who have won the most. And if we just look at the minutes that each individual player across Europe has played and compare all of their team’s goal differentials while they’re out there, then one player stands alone.

It’s … Napoli fullback Giovanni Di Lorenzo, who has been on the field for 60 goals scored and 16 conceded.

Right behind him: his teammate, deep-lying midfielder Stanislav Lobotka, who has seen his team outscore their opponents by 43 goals so far this season.

After that, Bayern Munich‘s Joshua Kimmich has been on the field for a plus-42 goal differential this year, then a number of other other guys have been out there for plus-41 goal-scoring margins: Haaland, Messi, Bayern Munich’s Dayot Upamecano, and the Napoli duo of Kim Min-jae and Andre-Frank Zambo Anguissa.

As for the Gunners, they’ve outscored their opponents by 37 goals while Gabriel, Gabriel Martinelli and Ben White were on the field.

So what?

That methodology isn’t great for any kind of fine-grained differentiation between players, but, well, it’s really hard to appear on that list without being a really effective soccer player. For Di Lorenzo in particular, basically one of three things has to be true:

– He’s a bad player with amazing teammates who are making up for his negative contributions

– He’s an average player with amazing teammates who are making up for his replaceable contributions

– He’s a very good player with very good teammates who are all contributing to one of the best collective team performances in the world this season

Which seems the most likely? Of course it’s the third option. The same goes for the likes of Anguissa, Kim, Gabriel, Martinelli and White — none of whom were necessarily considered title-winning-caliber starters before the season, but have shown themselves capable of contributing to one of the best teams in the world.

Now, I’m very much open to the argument that all of these players have been among the best players in the world so far this season, but I’m also doubtful that any of them have directly contributed more to winning than any other player in the world. If you added Di Lorenzo to, say, Liverpool, would they be having a significantly different season than they are right now?

A big part of the problem is that Di Lorenzo is nearly always on the field with nine other outfield players. By just looking at on-field goal differential, we don’t know how much of it to credit to Di Lorenzo and the relatively constant mix of teammates who have shared the field with him. We also don’t know the quality of the opposition faced by Di Lorenzo, compared to all of the other players in the world.

Building on a model that was created five years ago, a group of researchers just published a paper called “Augmenting adjusted plus-minus in soccer with FIFA ratings” in the Journal of Quantitative Analysis in Sports. The paper — and the approach — aims to dig deeper than the individual goal-differential numbers we’ve already been over.

First, it adjusts the plus-minus number for each player based on who they’re on the field with and who they’re playing against. That’s better, but it still mainly just produces a list of the players on the teams with the best goal differentials in the world. And we can assume that the best players in the world don’t all play for the best team or teams in the world. Unlike basketball, where there are more than 100 points scored per team per game, or hockey, where teams make some 400 subs per game, there isn’t enough scoring or enough interchange among players to be anywhere near confident that you know who is contributing what to a team’s goal differential.

To then figure out how to parcel out the credit for players who are on the field together, they needed a “prior” — or just a general guideline for how the players compare to each other. For their prior, the researchers used ratings from the video game FIFA, with the assumption that the ratings are essentially a crowd-sourced scouting system for the entire planet.

But any kind of rating — transfer values, a club’s in-house grades, a quantified “eye test” — can be used as the prior. Think of it this way: the prior is what your intuition is of all the players, and then it gets aggressively adjusted based on what actually happens on the field.

If a player has a high FIFA rating, but his club team plays better with him off the field, he’s still not going to rate well in this system. And if a player doesn’t rate well in the video game, but his Serie A-leading team clearly performs better when he’s on the field, he’s still going to rate quite well — just not as well as a teammate with a better prior.

So, the system … who rates well?

Before adding in the prior, the top five players across the Big Five leagues this season are, in order: Lobotka, Haaland, Messi, Borussia Dortmund‘s Julian Brandt and Real Madrid‘s Luka Modric. When you add in the prior, Lobotka drops down to no. 11 and Brandt down to no. 12. Bayern Munich’s Kingsley Coman bumps up to no. 5, Messi falls down to four, and Modric rises to three.

At no. 2, you get Bayern Munich’s Sadio Mane, aided by two things: 1) a long history of seasons suggesting that Sadio Mane is an incredible soccer player, and 2) most of Bayern Munich’s struggles this season occurring while he was injured. Throw in Liverpool’s struggles without Mane this year, and you can start to see how this way of looking at the game might start to un-blur some of the less-clear aspects of which players contribute to winning.

As for no. 1? Yeah, it’s Haaland. Now, it’s true that Man City are a worse team than last year after adding Haaland, but that ignores the fact that they’ve also lost Gabriel Jesus, Raheem Sterling, Oleksandr Zinchenko and Joao Cancelo, while the rest of the roster is a year older and has built up a massive minutes-load over the past two seasons.

The bottom-up approach (individual event stats) suggests Haaland might be the best player in the world, and the top-down approach (inferring individual performance based on team performance) says the same thing.

The beauty of soccer is that outside of a few eras of truly unmistakable individual dominance, we really can’t know who the best player in the world is with any degree of certainty. But someone out there is the best player in the world right now. And at this point in the season, no one has a better case than Haaland.

Credit: Source link