When Donald Trump defeated Hillary Clinton in the 2016 presidential election despite losing the popular vote by almost three million votes, many around the world wondered: “How is that even possible?”

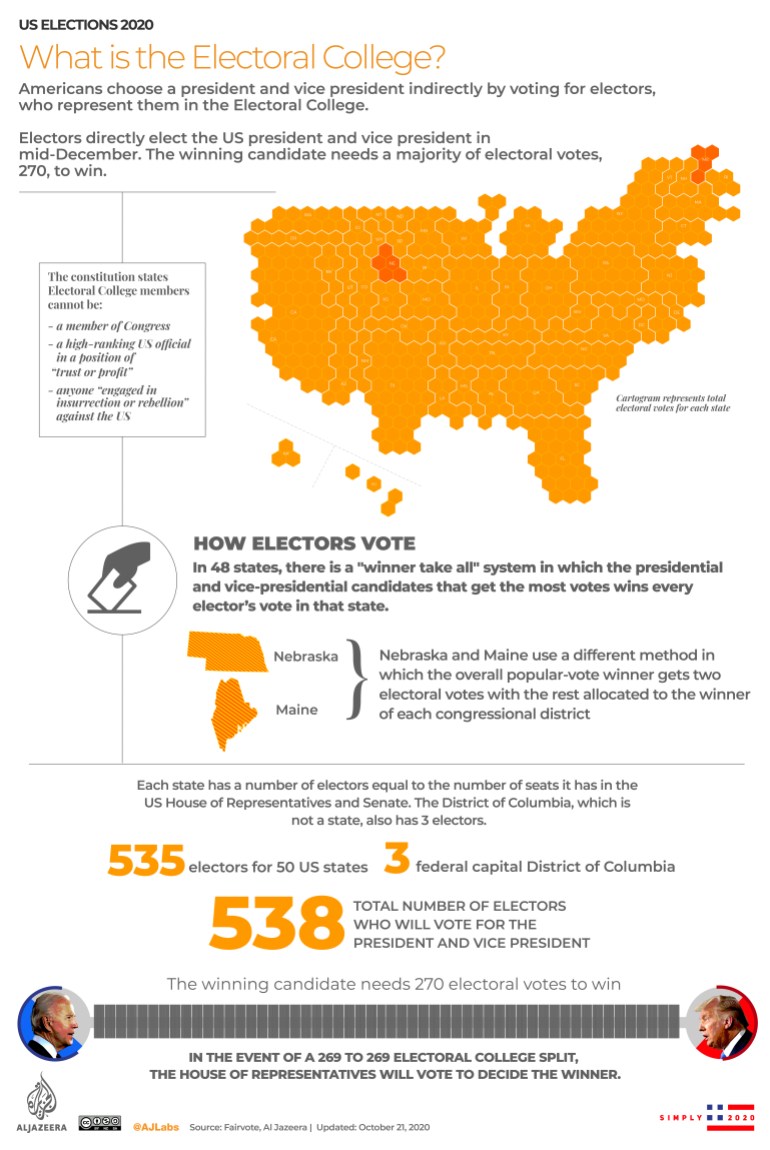

Unlike members of the US House and Senate, who are directly elected by voters, presidents, as spelled out in Article II of the US Constitution are not. The constitution says that the president and the vice president are elected as such: “Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress.”

In practice, what this means is that voters in each US state are voting for a slate of “electors”, who, after the votes are counted and certified, are pledged to vote for a presidential and vice presidential candidate. In 48 states and the District of Columbia, whichever ticket wins the most votes receives all of that state’s electors. In Maine and Nebraska, their electors are allocated based on the winner of each congressional district and the overall winner of the state.

The electors then meet as an Electoral College on a specified date by federal law – “the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December next following their appointment” (on December 14 this year) – to tally their votes for president and vice president.

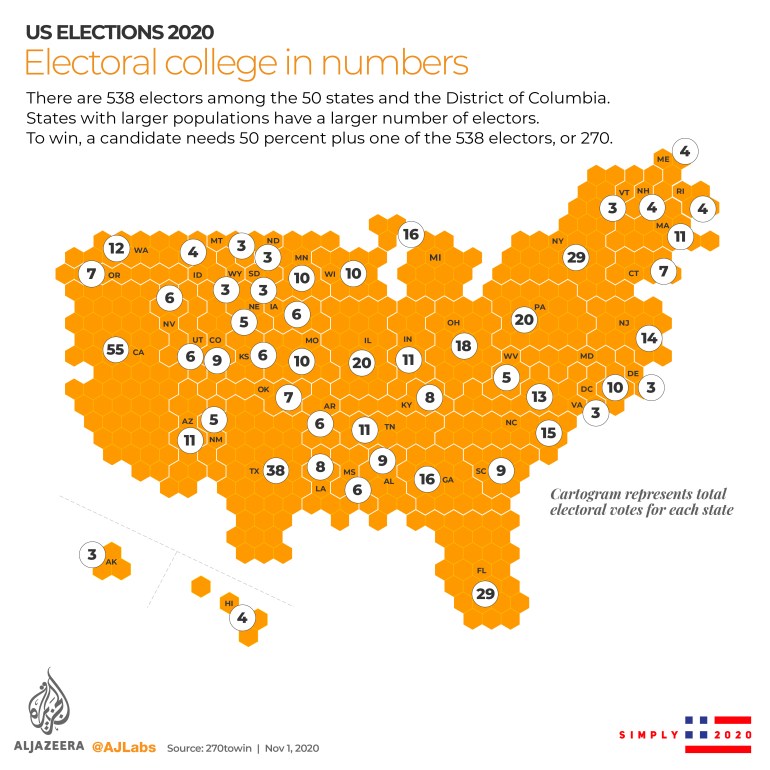

There are 538 electors among the 50 states and the District of Columbia. States with larger populations have a greater representation in the US House, therefore they also have a higher number of electors. A state’s number of electors is determined by adding the number of US representatives plus two, the number of senators each state has.

The District of Columbia, where the federal government is based, is not considered a state, and has no voting representation in Congress. However, in 1961, a constitutional amendment was ratified, giving the District of Columbia three electoral votes, the number of votes it would receive if it was considered a state, beginning in the 1964 presidential election.

To win, a candidate needs 50 percent plus one of the total 538 electors, or 270.

2016 was the fifth time in US history that a presidential candidate won the Electoral College but lost the popular vote.

So, how did Clinton receive more actual votes but fell short in the Electoral College? She won decisive victories in some of the largest states: A 4.26 million vote margin of victory in California, the most populous US state, a 1.7 million-vote victory in New York and a 944,000-vote victory in Illinois. For his part, Trump won three key electoral vote states by margins of fractions of a percent – Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin – and won Arizona, Florida, and North Carolina by less than 4 percentage points each.

The Electoral College is why each presidential race comes down to the handful of “battleground” states where polling is extremely close. The rest of the states are generally considered safely Democratic or Republican and those electoral votes can be predicted long in advance. This year there are about 10 states the candidates have focused their time and money, and it is those states that wind up having the most influence in deciding who the winner of the presidential election will be.

Credit: Source link