On occasion, even Bill Belichick needs some outside counsel on how to run his football team. Tom Brady’s departure from the New England Patriots should certainly mark one of those occasions.

Only when Brady was officially gone would Belichick call him “unfathomably spectacular,” one of the “original creators” of the Patriot program, and the game’s “greatest quarterback of all time.” The public display of affection from a man who hasn’t exactly spent his career as a walking, talking advertisement for PDA inspired a few questions.

How does one replace the greatest of all time, anyway? Did the Patriot Way permanently lose its way when Brady signed with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers? And can New England somehow contend for its 10th Super Bowl appearance under Belichick with Jarrett Stidham at quarterback?

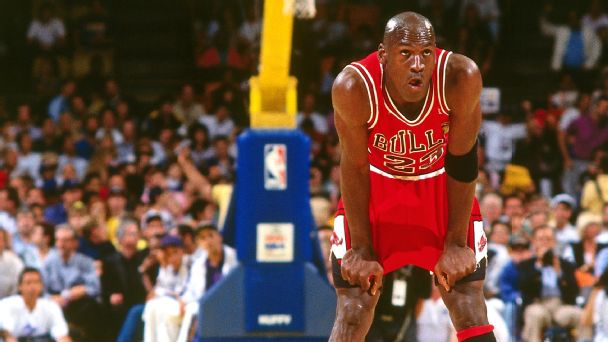

For that outside counsel to steer him toward favorable answers before the start of the 2020 season — whenever that might be — Belichick could spend some pandemic downtime studying the 1993-94 Chicago Bulls. As much as “The Last Dance” documentary has focused on everything the Bulls were with Michael Jordan on the floor, some of Phil Jackson’s finest work was done the season after Jordan suddenly retired for the first time, 3½ months after winning his third straight NBA title and two days before the start of training camp, leaving his teammates to deal with physical and psychological hurdles they were not favored to overcome.

2 Related

Those Bulls won 55 games against the odds and came within one highly questionable Game 5 whistle of likely eliminating the same team it had eliminated the previous three postseasons, the New York Knicks, in six games and reaching the Eastern Conference finals. “It was incredibly impressive,” said Jeff Van Gundy, a Pat Riley assistant for those ’94 Knicks and, later, Jackson’s chief antagonist as Knicks coach. “Phil’s triangle offense was never run better or more precisely than it was that year. The Bulls ran it better because they needed the offense to create more shots rather than to just run through it, find Jordan, and have him create. They didn’t have the ultimate bailout anymore.”

Just like the Patriots don’t have the ultimate bailout anymore in Brady. The dynastic comparison isn’t in perfect alignment, of course, because Jordan walked away at age 30 (before returning late in the 1994-95 season) after winning three of his eventual six rings while Brady left the Patriots at age 42, after winning all six of his New England rings, with virtually no chance of returning to Foxborough. The Bulls also had precious little time to adjust to their new reality; general manager Jerry Krause had announced in late September that Jordan, still grieving after the August murder of his father, had committed to showing up the first day of camp on Oct. 8. The Patriots will have months to ponder and process Brady’s exit before health experts allow them back in full pads.

The Bulls also had Scottie Pippen, a legitimate superstar. The closest thing the Patriots had to a Pippen, Rob Gronkowski, retired after the 2018 season and recently leveraged New England into a trade and a reunion with his personal Jordan, Brady, in Tampa.

But still, the presumed greatest NBA coach ever (Jackson) had to manage the loss of the last iconic team-sport athlete of the 20th century, just as the presumed greatest NFL coach ever (Belichick) now has to manage the loss of the first iconic team-sport athlete of the 21st century. Neither found it necessary to fill the void with star power. Jackson replaced Jordan at shooting guard with Pete Myers, a low-profile journeyman. It appears Belichick will replace Brady at quarterback with Stidham, last year’s fourth-round pick.

Belichick did go 11-5 with Matt Cassel after Brady was injured in the 2008 opener, and went 3-1 with Jimmy Garoppolo and Jacoby Brissett during Brady’s 2016 Deflategate suspension, but in both cases the coach knew the first-string quarterback would return. This time around, the first-string quarterback is gone for keeps.

“Whoever the quarterback is,” Belichick said last month, “we’ll try to make things work smoothly and efficiently for that player and take advantage of his strengths and skills. … And the things that either he doesn’t do well or needs more experience at or whatever the case might be, then we’ll try to minimize, or until those things improve, work around them.”

It sounded similar to what Phil Jackson said on Oct. 7, 1993, the day after Jordan’s announcement and the day before Chicago’s first practice. “I sat with my coaches and discussed the qualities we possess as a team and tried to evaluate what we can do for greater enhancement of those qualities,” Jackson told the Chicago Tribune’s Melissa Isaacson. “We talked about how we can try to hold down some negatives and accentuate some positives.”

Jackson described himself as intrigued and challenged by the task of navigating a Jordan-less season. Twenty-seven years later, associates of Belichick — just installed as the Coach of the Year favorite by Vegas oddsmakers — are describing him as feeling the same way about life without Brady.

Now comes the hard part, the part the bygone Bulls figured out to the surprise of those who picked them to plunge into the draft lottery. To understand what New England will confront without No. 12, it helps to understand what Chicago confronted and (to a degree) conquered without No. 23. Nothing about it was easy.

Phil Jackson stood before his players as camp opened and advised them to assume that Michael Jordan was permanently retired.

“You have to rely on one another,” Jackson told them.

Sitting in that room were B.J. Armstrong, Bill Cartwright, Scott Williams and Will Perdue, all contributors to all three championship teams and men who would play a combined 54 seasons in the league. The Bulls were stunned that Jordan had concluded, in his words, “that I don’t have anything else for myself to prove,” a decision made out of left field long before Jordan signed a minor league baseball deal with the Chicago White Sox. The Bulls were in dire need of leadership, and Jackson was up to the task.

“I think what he did most notably was help us identify our identity,” Perdue recalled last week. “In that first meeting, one thing he talked about was dealing with adversity. He asked us, ‘How do you guys want to be remembered?'”

Williams said some Bulls were upset that Pippen was grossly underpaid, and that pending free agent Horace Grant didn’t land a new contract, and that Croatian newcomer Toni Kukoc, the object of Krause’s globetrotting affection for three-plus years, had just arrived to much fanfare. “Jerry Krause kind of became the one common factor that we rallied around,” Williams said.

The Bulls started out 4-7, largely because Pippen missed 10 of the first 12 games with an ankle injury. Chicago’s Robin-turned-Batman returned to play at a league MVP level and carried a team that won 30 of 36 games to reach the All-Star break at 34-13. Armstrong and Grant would make the All-Star team for the first and only time in their careers, Kukoc would prove to be a credible talent, and Myers would serve as a steady defender, passer and game manager in Jordan’s place, making 81 starts. (Myers started only 19 games over his other eight NBA seasons.)

“The only thing we were missing was the best player in basketball,” Cartwright said, “but guys were given an opportunity to do more, and I felt they stepped up to the fact that Michael wasn’t there.”

Jackson had a great defensive coordinator in Johnny Bach, a great offensive coordinator and triangle guru in Tex Winter, and a great strength coach in Dick Vermeil’s brother Al. But the NBA, as they say, is a players’ league. “And Scottie was a man possessed that year,” Armstrong said.

Chicago’s team defense was better than it was with Jordan the previous year, surrendering an average of four fewer points per game. The Bulls swept Cleveland in the first round of the playoffs, compelling Pippen to write “4-peat” on his shoes for the conference semifinal series against the haunted Knicks.

With 1.8 seconds left in Game 3 and the score tied after a big Knicks comeback threatened to give New York a 3-0 series lead, Pippen famously refused to take the floor for Chicago’s final play because Jackson called Kukoc’s number, not his. “The most bizarre thing I’ve ever seen at any level of sports,” Williams said.

“You think of Bill Buckner, who had a Hall of Fame-type of career, and he’s known for one blunder. I was afraid that would happen to Pippen.”

The 10-part Michael Jordan documentary “The Last Dance” is here.

It had already been a wild and crazy night in old Chicago Stadium — a benches-clearing, second-quarter brawl had all but spilled into the lap of horrified NBA commissioner David Stern. On the Bulls’ last possession, Jackson needed a second timeout to regroup. In Pippen’s place, Myers would throw a perfect inbound pass toward the top of the key to Kukoc, who had established a habit of making last-second shots during the regular season. The swished 20-footer was reduced to a footnote in the postgame furor to come.

Despite his spectacular play all season, Pippen had trouble adjusting to his new leading-man role, getting arrested in January for having a loaded gun in his car (the charge was dropped), and later accusing Chicago fans of refusing to boo white players (Pippen apologized the next day). “He struggled with that new level of responsibility required of him,” Perdue said. “That gave him bigger respect for what Michael did 100 games a year.” Now Pippen had refused to participate in the closing seconds of a playoff game, testing the Bulls’ culture like never before.

“We pretty much exchanged words and I took a seat,” Pippen said that night of defying Jackson. “I think it was frustration.” Cartwright, the elder statesman, had tears in his eyes when he lectured Pippen in the locker room about his selfish choice. Perdue recalled that when Cartwright began talking, “You could see Scottie slinking down in his chair like, ‘Oh my God, what did I just do?’ … That was something that could have totally sunk our team.”

The Bulls’ team-centric values and maturity prevailed. Pippen controlled the Game 4 victory that evened the series, and then led Chicago to an 86-85 Game 5 lead before referee Hue Hollins called him for one of the most controversial fouls in NBA playoff history — a touch foul on Hubert Davis’ follow-through of a missed jumper with 2.1 seconds left. Davis made the two free throws, and after a timeout, Myers’ inbound pass to Pippen (not Kukoc this time) was knocked away. “I’ve seen a lot of things happen in the NBA,” Jackson said afterward, “but I’ve never seen anything happen like what happened at the end of the game.”

Pippen posterized a falling Patrick Ewing during a Game 6 blowout, and then the Knicks secured their liberating Game 7 victory in New York on the same afternoon in Huntsville, Alabama, that Jordan was going 0-for-5 at the plate for the Double-A Birmingham Barons. “A lot of people said they couldn’t win without Michael,” Ewing said that day. “But they proved they were a great team without him.”

Scottie Pippen still gets excited at the sight of his posterizing dunk on Patrick Ewing in the 1994 Eastern Conference semifinals.

As they accepted congratulations for a season well played, the Bulls were left to wonder what would have happened had they gotten a friendlier whistle in Game 5. “We are matched up against the Houston Rockets in the Finals,” Perdue said of the eventual NBA champs. The Bulls had beaten their would-be Eastern Conference finals opponent, the Pacers, four times out of five in the regular season.

“You don’t just lose Michael Jordan and think everything is going to be OK,” Armstrong said. “To hear we were one play away from getting to the conference finals, it blows me away when people remind me of that. Michael was Michael, and in spite of that we were right there.”

Can the New England Patriots be right there at the end of the 2020 season? The last dynastic team to lose a GOAT and live to tell about it believes the answer is fairly obvious.

“The Patriots are not a one-man team,” said Cartwright, now a men’s basketball adviser and director of university initiatives at San Francisco, his alma mater. “Are they going to be good? Their defense is great, they’ve got the same head coach and GM and scouts. Of course they’re going to be good. That’s insane to think they’re not going to be good.”

Yesterday’s Bulls sans Jordan see some of themselves in today’s Patriots sans Brady. “It’s very similar from the standpoint of leadership and teammates and how those pecking orders fall,” said Williams, a former Milwaukee Bucks assistant who’s now a broadcaster for Grand Canyon University basketball.

“I think if they have a winning record, quite honestly that would be a hell of an accomplishment.”

Former Bulls big man Will Perdue on the Patriots’ 2020 season without Tom Brady.

“It doesn’t matter what locker room or sport, a disruption of that magnitude, Jordan or Brady, has to be dealt with and overcome. You can’t have one person pick up a baton that big and heavy and carry it. You have to have a collection of guys do that, and you need strong leadership. Belichick is a guy who has the same presence that Phil Jackson did. He’s got a system that works, and guys there have been playing in that same system. He can plug in another player in that system like Phil plugged Pete Myers in, and the other guys will figure out ways to step up and not let the absence of Brady loom so large.”

Nobody knows if Jarrett Stidham is capable of only being a serviceable placeholder, or if, like Brady, he will someday prove he should have been the very first player taken in his draft. But it’s worth nothing that Belichick liked what he saw from Brady in practice long before the 199th pick in 2000 replaced the injured $100 million franchise player, Drew Bledsoe, early in 2001. Perhaps the coach has seen subtle signs from Stidham that put future Super Bowl stardom within the realm of possibility.

But for now, New England is better off assuming its new quarterback will start off as a competitor with Myers-like intangibles, and lean instead on its pedigree, professionalism, and what was a league-leading defense in 2019.

“Tom Brady got all the headlines, just like Jordan got all the headlines,” said Armstrong, now a player agent, “and they’re spectacular and should get the headlines. … But the first thing you need to become a good team is you’ve got to learn how to stop somebody. The one thing people didn’t understand about the Bulls was that we were a very good defensive team. With Brady, you’re obviously losing offense. So to me, let me figure out the defense first. If it’s 0-0, you’re not losing. If you can stop somebody, that gives you an identity.”

Brady’s decision to leave for the Bucs didn’t diminish the New England defense or destroy its culture, not with pro’s pros the likes of Devin McCourty still among the Patriots defined by their winning muscle memory. Brady’s decision also didn’t temper Belichick’s desire to win a seventh Super Bowl title; in fact, it poured gasoline on that fire.

“With great coaches like Belichick and Phil Jackson,” Armstrong said, “the one common denominator I learned as a player is you have to have impeccable leadership. There are a lot of coaches who know X’s and O’s, but there aren’t a lot of people who understand leadership. … The Patriots still have that.”

Belichick can coach them up to a point. The Patriots will need to rely on one another, and play for one another, like the Jordan-less Bulls largely did. Of the old Bulls asked about the new Patriots, Perdue, now an analyst for NBC Sports Chicago, sounded the most concerned about New England’s prospects. “I think if they have a winning record, quite honestly that would be a hell of an accomplishment,” Perdue said.

“I remember watching Patriot games, even last year when Brady didn’t have the best of years, and you always had that feeling as a fan that as well as opposing defenses played for 3½ quarters, the last thing they wanted to deal with was leaving time on the clock to give the ball to Brady and allow him to win it. Now Belichick has to figure out a way to get the offense ahead of this, because there’s not that intimidation factor or aura of Tom Brady sitting on the sideline, masterminding it and figuring out how to beat your team.”

Perdue said this year’s defense will have to be even better than last year’s to elevate the offense, and wondered aloud if the Patriots’ skill-position players are good enough to keep Stidham out of third-and-long situations. “Do they have a solid leader on the offensive side of the ball?” Perdue asked. “It could be a receiver, running back, the new quarterback, a lineman, just someone who can pull the offense together. I’m not saying this offense has to be great, but it has to be adequate.”

Perdue said the 1993-94 Bulls were probably closer, as a group, than his other seven Chicago teams, including the three that won championships, because they needed to rally around Jordan’s absence. He understands that the Patriots are known for their chemistry, and that they might rally around Brady’s absence, too, while playing for a coach who is every bit the juggernaut that Jackson was with the Bulls and Lakers.

“I still think they can be successful,” Perdue said.

How successful? It’s awfully hard to legitimately contend after your GOAT goes searching for greener (or more tranquil) pastures. But history and circumstance suggest it would not be any smarter to write off the Patriots without Tom Brady than it was to dismiss the Bulls without Michael Jordan in a different time.

Credit: Source link