A week ago, Pep Guardiola did it again: He took the more talented squad into a match, overcomplicated his tactics and made the team worse than the sum of their parts.

When the lineups were announced for the match at Arsenal, the pregame XI had Bernardo Silva, an attacking midfielder, playing at left-back. Surely, this was just another example of the inadequacy of the static presentation of the soccer lineup. Players, especially Silva, are in constant motion — and where they position themselves with the ball and without the ball often look drastically different. With Kyle Walker listed as City’s nominal right back, this would turn into more of a back three with Silva functioning much further forward… right?

Then the match started and, sure enough, Bernardo Silva, who had never played a game at fullback in his six seasons with Manchester City, was playing like your run-of-the-mill left-sided fullback. Tucking into the back four when Arsenal were in position and tasked with shutting down perhaps the best right winger in the league, Bukayo Saka.

It went about as poorly as you might expect. Silva, according to the site FBRef, is 5-foot-8, 141 pounds, and he doesn’t have the kind of up-and-down athleticism required from most modern fullbacks. Saka had no trouble getting forward, while Silva committed three fouls in the first half and finally received a yellow card in the 46th minute. Although the match was tied come halftime, Arsenal had dominated the flow of the game and only conceded after a poor back-pass from Takehiro Tomiyasu.

Fifteen minutes into the second half, Guardiola took Riyad Mahrez off for Manuel Akanji, bumped Nathan Ake out to left-back, and pushed Silva into the midfield. With their players in their more traditional positions, City took back control of the game — and at least for a few days, the title race — en route to a comfy 3-1 win.

The lesson, for Guardiola or for any other coach with the more talented players, seemed to be: keep it simple, stupid. Just put your best players out there in their best positions, and you’ll probably win the game. But the more I thought about it, the more I started to wonder whether Pep wasn’t circling around a bigger idea: What if some of these players have been playing in the wrong positions all along?

What even are positions, man?

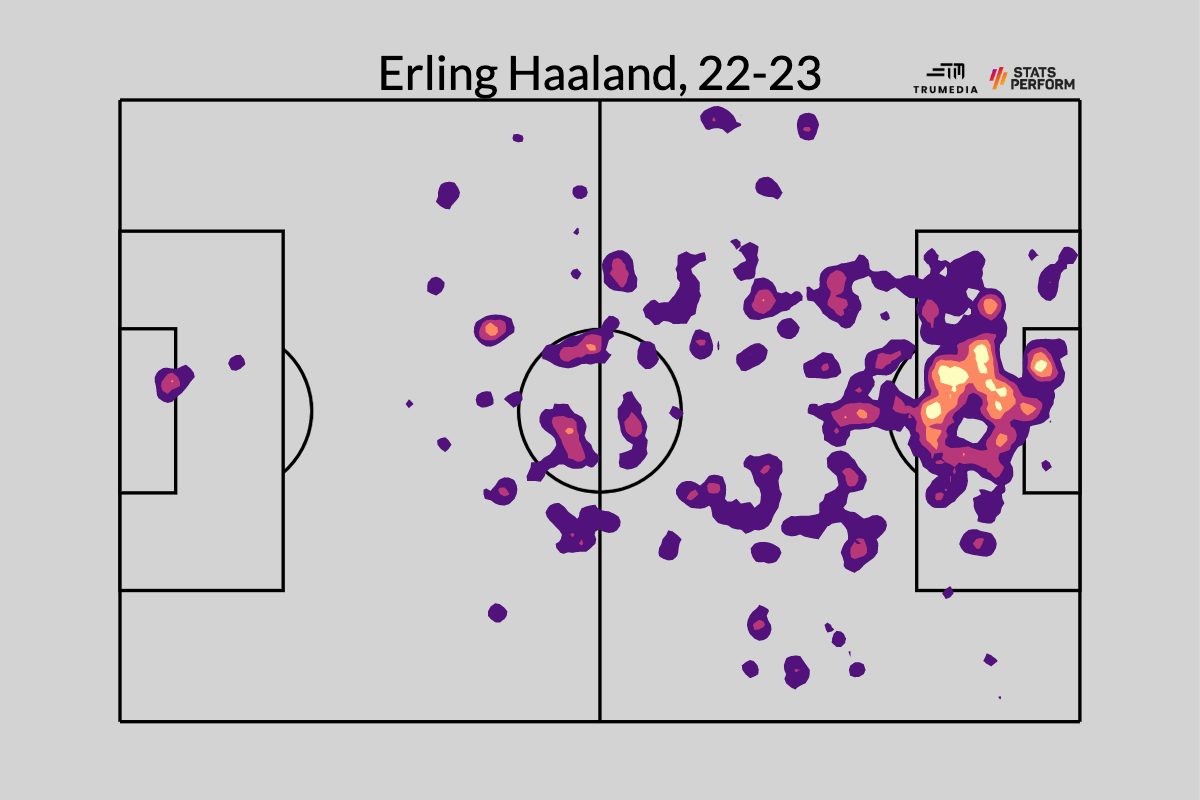

Every right-back is different — both in how the individual player interprets the position and in what the individual manager asks that player to do. No two central midfielders will make the same decisions on the ball or find the same pockets of space within the same flow of the same match. And have you seen Erling Haaland and Harry Kane play center forward? One lives inside the box:

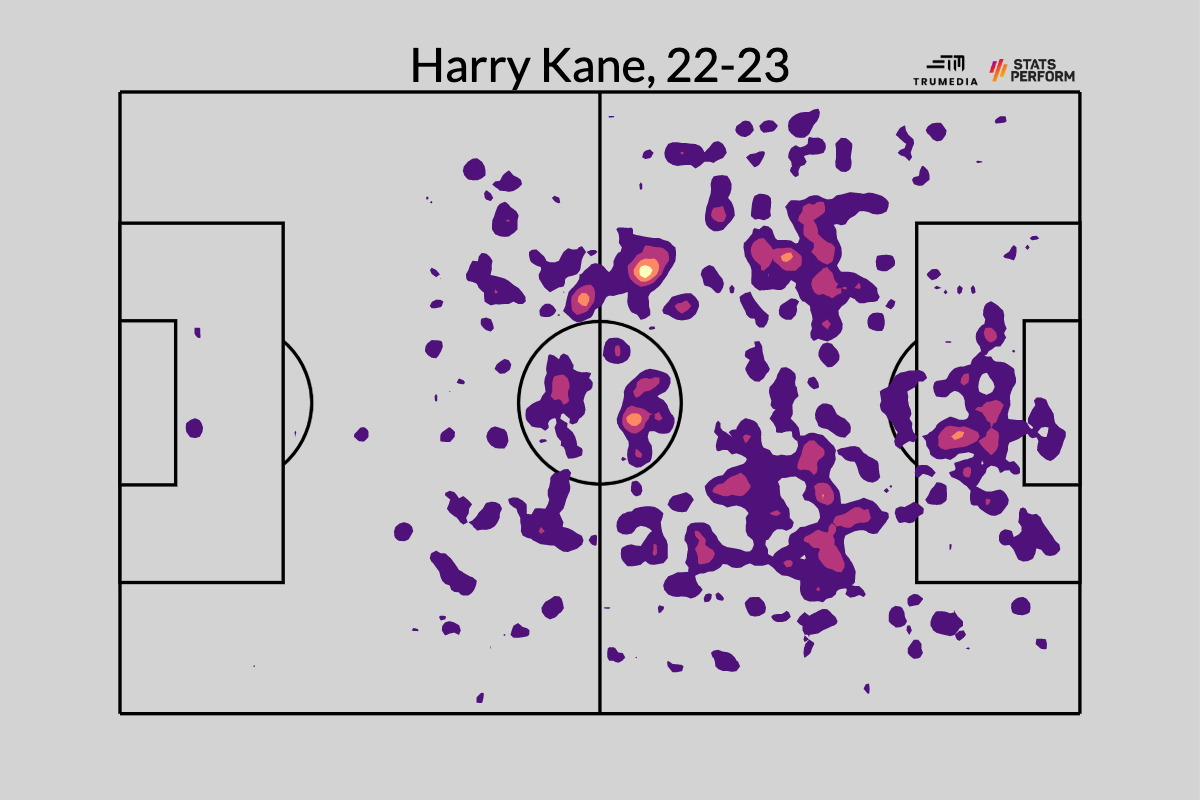

The other roams up, down, and across the attacking half:

Soccer, like every other major sport, is moving toward positional flexibility. Some call it “positionless” play. Of course, we’ve been here before. Not just with Johan Cruyff’s Total Football-playing Netherlands and Ajax sides, but Hungary, Argentina and Austria before them. Perhaps the technocrat-ization of society bled into soccer, with workers being cordoned off into their specific pathways based on their specific areas of expertise. But whatever the reasons for the movement away from a more holistic style of play in the latter part of the 20th century, we’ve officially re-entered an era where players across the field are frequently expected to contribute in all aspects of play.

There’s a growing recognition of the idea of the role: Every team needs players to do certain things — progress the ball, press, create for their teammates, keep possession, win balls in the air, score goals, etc. But not every team needs the same positions to take up the same tasks.

Using event data, the analyst Michael Imburgio created a model that divides players into seven buckets: central defenders, wide defenders, deep midfielders, central midfielders, creators, dribblers, and finishers. Those seven roles then get divided into their own sub-roles.

Forwards are defined broadly by Imburgio as “Attacking players that play high up the pitch and often look to shoot when they receive the ball”. But within that, there are “roaming forwards” (drift wide and play crosses), “progressive forwards” (drop deep and play passes up the field), “target forwards” (drop in to aid in buildup play and win balls in the air), and “poaching forwards” (stay central and mostly get on the end of moves).

Interestingly, Kane has developed from a poaching forward to a roaming forward to a progressive forward over time. Haaland, meanwhile, has always been a poacher. Other roamers include Mohamed Salah, Kylian Mbappe and Luis Suarez, while Aleksandar Mitrovic, Dusan Vlahovic and Wout Weghorst pop out as clear target forwards.

The origin of positions

Think about how a player becomes a midfielder or a fullback or a striker. Somewhere along the way in the youth level, he plays a position because a coach decides he has the right attributes for the role or because a club has too many forwards and so he gets pushed down to fullback. Players aren’t being developed in a vacuum, and most clubs aren’t specifically trying to optimize each player’s individual development.

On top of that, players change as they age, train and learn more… and the game changes around them, too.

“Overall, I think we should assume a player’s traditional position is their best role, but we also shouldn’t be scared to test it,” said Bobby Warshaw, a strategic consultant for clubs and investors. “Most players were given a position 10 years prior by a youth coach during a different era of football in a different game model and at a different point of their personal maturation.”

Ultimately, the main game-to-game task of a manager is to get his best players on the field. The tactics have a marginal effect; so does whatever he’s helplessly screaming from the sideline and whatever subs he decides to make. But — by far — the biggest effect a manager has on whether or not a team wins a game comes simply from what players he puts on the field from the start. Once the whistle blows, the players (and the randomness inherent to a bouncing ball) decide who wins the game.

The job of a manager, then, in the broadest sense is to constantly be re-evaluating who his best players are, based upon the opponent and the specific moment in time. And if that’s your job and you’re completely ignoring the possibility that some of your players might do better in a different spot on the field that would then raise the collective talent level of your lineup, then you’re handicapping yourself.

“What is a position? It’s a set of pictures and attributes,” Warshaw said. “If you’re looking for a center midfielder who can provide ball retention, reactions, ground coverage, and positional discipline — we can all name a bunch of outside backs with those attributes. There’s certainly a learning curve to figuring out the moments in any new position, but is that familiarity worth more than player quality? Maybe, and that’s unique to every player. But it feels to me like clubs are a little too far down the scale than they should be.”

How to find a fullback

Most of the positional changes work in the way that Guardiola tried to make his work against Arsenal: backward. The most skilled players tend to play higher up the field because there’s less space and every action requires a much higher degree of precision.

“When attacking players move to better clubs, or get older, they tend to move backward on the field, not forward,” said Omar Chaudhuri, Chief Intelligence Officer at Twenty First Group. The example Chaudhuri likes to use is Victor Moses, who was a successful winger at Wigan and then a failed winger at Chelsea — until Antonio Conte moved him to wingback and he made 29 starts as Chelsea won the Premier League with 93 points in 2017.

“Acknowledging that data-based models struggle to quantify midfielders, my mental model says that center-mids tend to be better footballers than outside backs, so my first instinct is to find the best center midfielder who isn’t starting and ask myself if they could play outside back in this game model,” Warshaw said.

This, of course, is what Liverpool did with Trent Alexander-Arnold. A talented midfielder at the youth level, he was moved to fullback because there was less competition for that spot within the senior team. His main skills — vision, tight-space movement, passing precision and range — are stereotypically midfielder skills. Instead, he’s gone on to become one of the most decorated fullbacks of his generation, and all of it before his 25th birthday.

Recently, Liverpool’s Champions League opponents, Real Madrid, seamlessly plugged midfielder Eduardo Camavinga into the left back role to cover up a glut of injuries at the position. Not without controversy, this is also what the United States Women’s National Team has done with Crystal Dunn. Although those players might not master the traditional fundamentals of the fullback role, the impact they can have from doing things other fullbacks can’t do greatly outweighs any downsides.

“We all like to get detailed in our analyses, but it seems that there’s a general concept of ‘quality’ that supersedes the nuances of how they get there,” Warshaw said. “The ability to see options under pressure, to read an opponent’s center of gravity, to know where a ball will land, to think ahead, to execute a pass — either you can do those at a certain level or you can’t, and those probably matter more than how to shape your body on the back post.”

For the biggest clubs with massive payrolls, perhaps there is some talent hiding elsewhere on the roster. While Wout Weghorst seemed like a baffling signing for Manchester United — a target forward who scored two goals in 17 starts for relegated Burnley last season — he started United’s most recent Europa League match, against Barcelona at the Camp Nou, as a central midfielder. It seemed absurd — he’s 6-foot-5! — but he hadn’t been effective as a center forward, and well, United outplayed Barcelona with Weghorst in the midfield. (Yes, they drew, 2-2, but United created significantly better chances.)

For smaller clubs, these ideas might unearth value in the transfer market. Rather than chasing after expensive attackers or scouring the globe for hidden gems at the game’s most premium positions, perhaps there’s a midfielder sitting on the bench at a big club: not good enough to play as a forward for a Champions League contender, but still talented enough to score goals for someone lower down the ladder.

So why don’t more clubs try this? Simply put, the soccer world — where there’s relegation, and revenues fluctuate with each passing year based on performance — remains way more conservative than the American sports landscape.

“If you lose with standard squad selection, the problem could be a variety of things,” Warshaw said. “If you lose by playing a center back at center forward, then your decision becomes the talking point.”

On top of that, soccer is hard enough to understand as it is. Calling into question a fundamental tenet of the sport further complicates an already impossibly complex game. “A club already has too many decisions to make for their resources, and it’s tough to add another into the equation,” he said. “In this mess of a sport, I can understand why someone just wants to set positions as fact.”

Credit: Source link