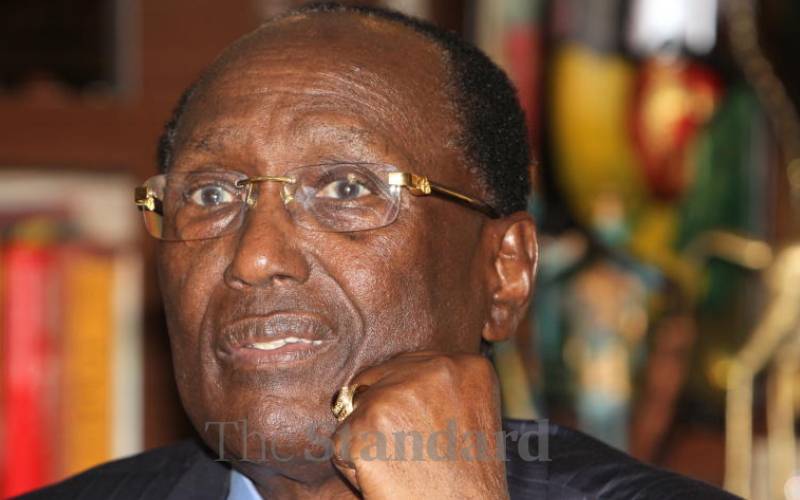

Chris Kirubi has been eulogised in laudatory terms these last few days. That is as it should be. He was an exceptionally successful businessman, a larger than life presence on Nairobi’s social scene, a bon vivant possessed of exquisite and enviable taste in all things, an erudite conversationalist on a wide range of subjects, an ever-present mentor, a generous benefactor to and patron of many

That is the Chris Kirubi eulogised by many. I join them in paying tribute to that Chris. But there is another essential but little known Chris Kirubi: a brilliant Chris, an intensely and proudly African Chris, one who played a decisive role in cementing Kenyan-Africans’ place at the top table of the big corporate world. It is this Chris Kirubi that fascinates me, and to whom I make this tribute

Bear with me as I wind the clock back. It is the 1970s. Kenya is in the midst of establishing and cementing its post-colonial economic and business structure. It is an age of established business titans still dominating the landscape, with individual clouts larger than what today’s corporate moguls wield, notwithstanding the larger resources available to the latter. Bruce McKenzie, Jack Benzimra, Sir Eboo Pirbhai, Jack and Tubby Block, Col David Dobie, Tiny Rowland, Michael Blundell, Sir Ernest Vasey, aAnd many others. Names largely forgotten today, but who in their day moved and shaped the economy, bent it to their will.

Commanding heights

But, where are the Africans in this corporate mosaic? To be sure there were Africans holding key economic and business positions. But these weren’t capitalists, they didn’t dominate the commanding heights of the economy as entrepreneurs and businessmen. Instead, they were largely agents and in a real sense creations of the new Kenya State.

They ran the big state enterprises, the behemoths that dominated key sectors: East African Power & Lighting, East African Posts & Telecommunications, East African Railways & Harbours, East African Airways, and ICDC.

Younger readers familiar with the troubles of some of the successor companies to these entities will find it hard to believe that heading these institutions was once the apex of young Africans’ corporate ambitions. From these perches, they would find their way gradually to private sector corporate Kenya, and along the way hope to build up capital to become modest corporate players in their own right.

Likewise, ambitious young civil servants served their apprenticeships in government before going off to corporate Kenya. And there were also young Africans getting to the top of private sector corporate giants without being apprenticed in government.

Among these Africans then starting to make a mark in corporate Kenya were Joe Wanjui,Udi Gecaga, Ken Matiba, Ngengi Muigai.

But they were few, underscoring the painful fact that black Africans were still largely absent from this world. This is the scene that greeted young Chris as he emerged into the business and corporate world; one where Africans, while increasing in number, were still relatively few, and certainly were not yet corporate titans in the sense understood then and now.

Close range

I was lucky enough, as a teenager and then as a young adult fascinated by the rapid political, social and business changes Kenya was then undergoing, to have a ringside seat observing the new boys (there were no women in that rarefied corporate world). For reasons that need not concern us here.

I got to see Chris and others from quite close range.

Remember Chris was walking among giants. He didn’t have the family background to be there, and by all rights should have been cowed into timidity by the very frightening men he found himself amongst, men who dominated headlines, ruthless movers and shakers.

But he neither quaked nor quailed. Years later, when he and I had become friends in our own right, rather than, in my case, by reason of family, we discussed this phase of his life. His position: he didn’t envy or fear these people. Instead, he was determined that he was as good as they were, that what he needed to do was learn from them as much as he could. Even at that early stage, he was quite clear that he was going places.

And so he went about imbibing business lessons from those who had come before him, including the inevitable intertwining of business and politics. He knew that then as now, managing politics and influencing policy were critical success factors for those aspiring to become the big beasts of capital. But he also learnt from these tycoons not to become overly fond of or be overwhelmed by politicians, to maintain a close but wary distance from them.

Refused to be caged

And as his career evolved, and as I came to know him more as a person, another side of him gradually emerged. He was, there is no other word for it- an Africanist in the best meaning of the word. He believed Africans could and must play on the global corporate scene. He couldn’t understand the inferiority complexes that permeated so many in positions of power.

He empowered young Africans in his businesses, an early indication of his passion for Kenya’s youth and their future. He worked hard and played equally hard. He flaunted his success, both because he enjoyed it, and also because he wanted the rest of us to learn to accept and enjoy success.

He refused to be caged into a semblance of conventional behaviour. He wasn’t a rebel, but he was impatient, willing to stretch the rules of what was deemed acceptable behaviour for people in his position. He was one of a kind, and proud of it.

The ICDC story

In the 1990s I worked closely with Chris as his banker, then as his investment adviser. I also had a ringside seat as he strove mightily to operationally demerge ICDC Investments from ICDC. This last cemented my respect for his strategic acumen.

For many years ICDC Investments, a listed entity in which at that time ICDC held 25 per cent and about 15,000 Kenyans owned the rest, had been a sleepy appendage of ICDC, its money welcome but its voice unheard.

Quite a few investors in London had seen its potential, but a quirk in its charter, which then restricted ownership to Kenya citizens, meant foreigners couldn’t mount a takeover.

Quite where and how Chris got the idea to give it a go is a story for another day, but in short order he had built up a strong equity position in ICDC Investments, and also succeeded in convincing Government to let the company go its own way, run its own show, with him as controlling shareholder.

What made me admire Chris, even more, was that at about the same time I and other investment bankers had been trying, with little success, to convince moneyed Kenyans to become serious stock market players, including taking controlling positions.

Chris did not need us telling him this; he understood it instinctively and went for it. And then he proceeded to make a success of this bold gambit, with ICDC Investments, now renamed Centum, going on to carve quite the swathe in the investment world. And along the way Chris nurtured a new breed of young business leaders,Tony Wainaina,David Owino,James Mworia.

In later years, and while not slackening his business pace, Chris became interested in the forces that drive economies forward. He read widely, attended and kept up with developments at Harvard Business School. He was determined that Africans would find their place in the global corporate sun, and had unbounded faith in the transformative power of business and of the private sector.

Unabashed capitalist

He was an unabashed capitalist, had little truck with the endless whining about the unfairness of life so beloved to many of us. He detested the corruption that has so permeated our society. My last extended conversation with him, soon after his return from his first round of treatment in the US, was devoted almost entirely to this subject, how we needed to fight corruption.

He did not just speak behind closed doors to only a few on this subject. I will never forget a seminal moment in 2015, during a Presidential Roundtable which Chris attended as part of the KEPSA team, when he let rip volubly and relentlessly at a Cabinet Secretary then under sustained media pressure for alleged corruption.

This was done in the full glare of President Kenyatta, other senior government officials, including said Cabinet Secretary, and a multitude of business people. I like to believe that it was this episode that led to the President appointing, at the end of that Roundtable session, a Government-KEPSA team to come up with anti-corruption recommendations.

Enjoyed winning

This was the Chris I wanted to highlight. A smart businessman, yes, But also a nationalist and Pan Africanist. A strategic thinker, much as he tried to hide this side of himself by emphasizing and playing up his colourful public persona. A man consumed and driven by his pride in and passion for his people, his unwavering belief that Africans could do it.

A man who refused to let the tough cards life had dealt him at birth dominate or determine how his life would unfold. A Pied Piper, in the best sense of that phrase, who showed us possibilities, and gave aspiring business leaders and entrepreneurs the confidence to break out and do their thing.

Was he a saint? No. Chris in full business flight was awesome to behold. He took no prisoners, was famously unsentimental about investments, practiced caveat emptor with relish. He enjoyed winning, did not have time for losers. And woe betides anyone who thought he was a soft touch for a donation. He was hard-nosed, but hard-nosed for the greater good.

So fare thee well Christopher John Kirubi. You lived hard and well. You built enterprises employing thousands and adding real value to the economy, lasting reminders of your phenomenal business skills.

You had your fair share of errors and missteps along the way. But you stayed the course, guided by your own North Star.

When the scales are weighed of all you have done, I am confident you will be judged to have lived honourably, to have lived for a greater purpose, and to have left the world a better place. You were, truly, one of a kind

John Ngumi is the Chairman of the Board at ICDC?

Credit: Source link