Sure, Manchester United had a nice October. And OK, they are currently in sixth place in the Premier League. But, I mean, have you seen them play?

United eked out a recent stretch of five wins from six matches, thanks to five of those matches and all of those wins coming against teams in the bottom half of the table. Although United are just two spots out of fourth, they have the 12th-best goal differential in the 20-team Premier League. The worst goal difference to finish fourth in the Premier League was Everton at minus-1 in 2004-05. Next-worst after that was Chelsea at plus-15 in 2019-20. The average is plus-27. Man United are at minus-3.

In other words, they’re incredibly fortunate to even be in sixth place.

United just lost 3-0 at home to Bournemouth. And their previous loss came to a reeling, injury-plagued Newcastle team that’s been getting run off the field by every other team they meet. Next up, Bayern Munich come to Old Trafford for the Champions League. Then, it’s off to Anfield to take on the team sitting atop the Premier League table, Liverpool. Although Bayern have nothing to play for in the last game of the Champions League group stages, United are still underdogs, according to ESPN BET. And although United finished ahead of them last season, United’s implied win probability against Liverpool is just 15%, based on the betting odds.

After last season’s third-place finish and a summer that saw more than €200 million spent on transfer fees for four players at key positions, why is this team suddenly so bad?

Let us rank the reasons, from the most blameworthy to the least.

1. The owners — specifically, the Glazer family

This is easily the most important and the most boring reason for Man United’s struggles.

The only competitive constant for most sports teams is the person who owns the team. It’s a pretty depressing way to think about sports, but when we talk about why and how teams win over a long stretch, the people who cut the checks and decide who to hire are the primary drivers of performance.

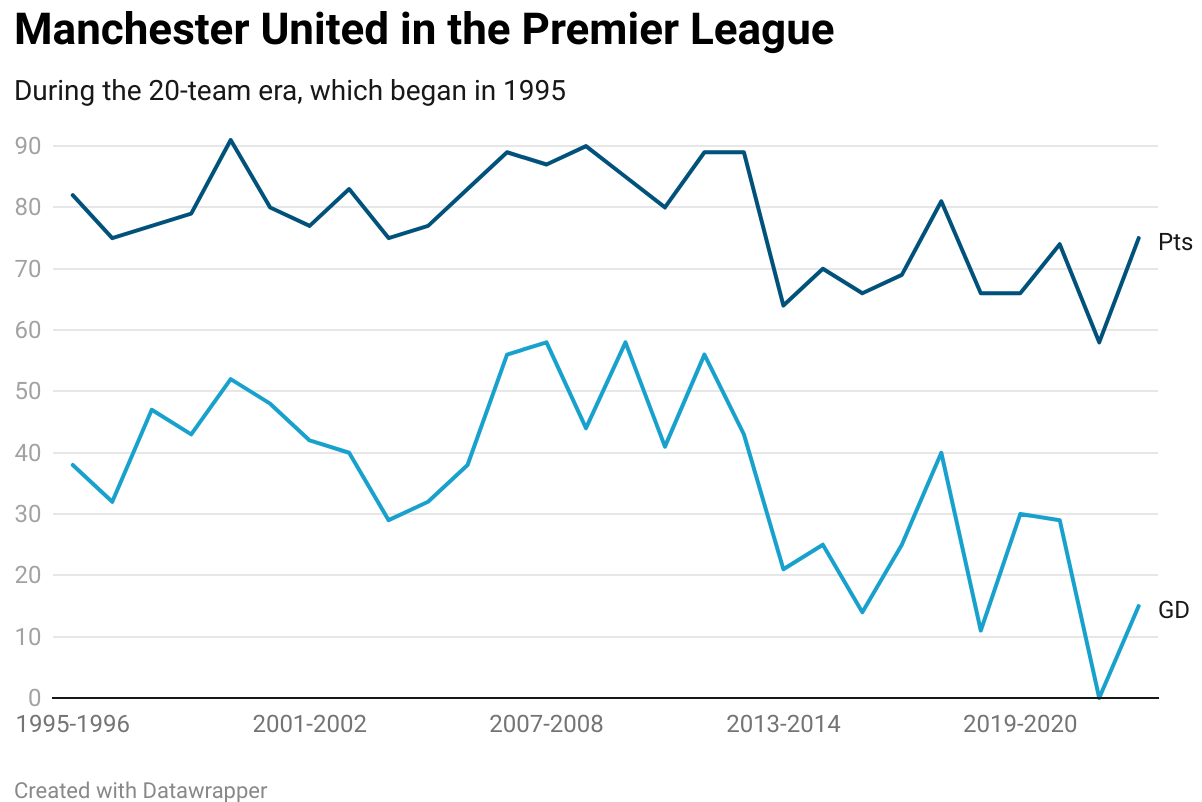

The Glazers completed their debt-funded takeover of the club in 2005 and Manchester United’s last Premier League title came in 2013, which was manager Sir Alex Ferguson’s final season with the club. There have been two constants since then: volatile season-to-season performance and the Glazer family.

Teams like Liverpool and Manchester City have professionalized the way their teams are run, investing big money in data departments and building a decision-making apparatus above their two superstar managers. United have, uh, not done that. They didn’t appoint their first director of football until after the COVID-19 pandemic, and all I get is laughter whenever I mention “analytics” and “Manchester United” together in the same sentence to anyone who works in European soccer.

Almost all of the football operations were controlled by Ferguson when he was with the club, but the game has modernized at light speed in the decade since. Clubs are too big, and the competition is too fierce for one man to coach the team and scout opponents and identify new talent and negotiate with agents all by himself anymore. While the club has done a fantastic job at modernizing and exploiting the commercial side of Manchester United, the Glazers have seemingly been holding a decade-long shrug while they stare at the vacuum created by Sir Alex’s retirement.

And so, in a grand sense, this is all their fault. Players and managers can fail you once or twice, coaches can turn out to not be who you thought they were, promising prospects can flop and so on, but it’s been happening over and over and over again, over the past decade. Just look at that chart again in the post-Ferguson years: there’s a clear pattern of reasonable success followed by massive failure followed by reasonable success followed by massive failure. Plenty of players and coaches and executives have cycled in and out while that pattern persisted. The only people who were there the whole time are the people who own the team.

After Ferguson left, the Glazers essentially let former banker Ed Woodward — the guy who helped them complete their takeover of the club — run the team. United’s failed attempt to form and join the European Super League in 2021 led to Woodward’s eventual ouster, but in 2018, he seemed to sum up the attitude of his owners when talking to an investor who was worried about the team’s poor play: “Playing performance doesn’t really have a meaningful impact on what we do on the commercial side.”

Since 2013, United have averaged the third-highest annual revenues of any club in the world. Since 2013, United’s average finish in their own domestic league is worse than fourth.

2. Recruiting mediocre players (and overspending for busts like Antony)

United’s revenues and wage bill are so high that even a fourth- or third-place finish should be a disappointment. But performance has been so volatile from season to season over the past decade that every comfortable top-four finish feels like a triumph, since it’s typically preceded by a managerial flameout and failure to qualify for the Champions League the year before.

And so the cycle continues apace: sixth two years ago, third last year, and back down to sixth this season. However, this might be United’s worst season yet in the post-Sir Alex era.

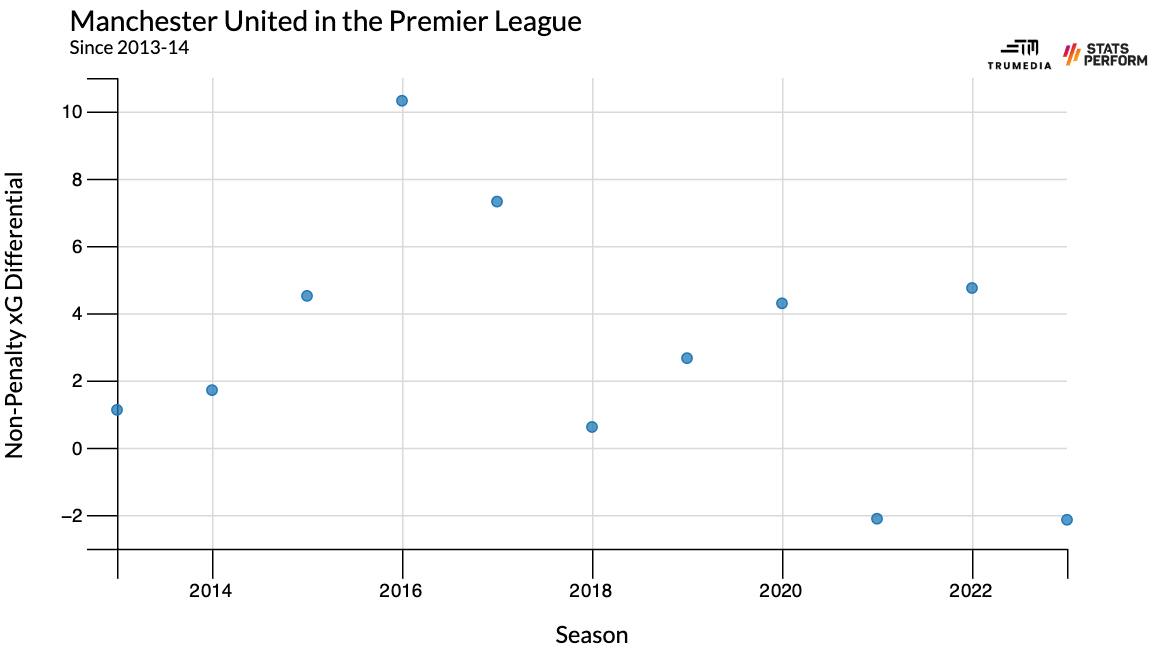

In the first 16 matches of the previous 10 seasons, the club had never been in the red when it came to scoring and conceding goals. This season, they’ve scored 18 goals and conceded 21. More predictive than that, though, is the combined quality and quantity of the chances they’re creating and conceding as measured by expected goals, or xG. By expected-goal difference, this, too, is United’s worst start to a season since Sir Alex left.

United have created 23.3 xG and conceded 25.4, for a differential just slightly worse than we saw at this stage of the 2021-22 season. So, while there’s a larger pattern of failure that falls at the feet of the Glazers, there are all kinds of other particular failures that combine to create the following fact: United have the highest wage bill and the 13th-best goal differential in the Premier League, at the same time.

Beyond the larger dysfunction bred by the way the Glazers have run the club, the biggest reason this team is so bad is that their players aren’t very good. Just take a look at this list of the 11 most-used players this season: Bruno Fernandes, André Onana, Diogo Dalot, Marcus Rashford, Victor Lindelöf, Scott McTominay, Harry Maguire, Rasmus Hojlund, Alejandro Garnacho, Antony, and Casemiro.

How many of them would start for Manchester City, Arsenal, or Liverpool? The answer: Probably zero!

Bruno has almost single-handedly kept United in shouting distance of the top four for the past five seasons, but it’s unclear how his individualistic approach — lots of vertical passes, lots of turnovers — would fit within the systems of Pep Guardiola, Mikel Arteta, or Jurgen Klopp. None of the other players would improve any of this season’s three title contenders, and that’s despite United paying more money in wages for these players than those teams do for theirs.

In one sense, that absolves manager Erik ten Hag for some of the blame. Except, due to the club’s dysfunctional decision-making structure, the manager seems to have had a large influence over who the club has signed since he arrived.

United have as much money to spend as essentially any other club in the world. Outside of, say, a group of like 30 or 40 guys at the other richest teams in the world, they can sign pretty much anyone they want. And yet, they’ve signed 12 players on either permanent deals or for loan fees since last summer, and eight of them have a direct connection to Ten Hag himself, the agency he’s represented by, or the clubs he used to coach at.

That’s either an awful coincidence, or an awful process. And, well, it’s quite clearly the latter.

Antony, Ten Hag’s former player at Ajax, became the club’s record-signing last summer, and he’s scored four goals and notched two assists in 37 league games since joining the club. To clarify: He is an attacker. The most likely outcome for Antony’s career is that he goes down as one of the worst-ever signings in the history of the Premier League. We can’t have the same level of confidence about the outcomes for 20-year-old striker Rasmus Hojlund, who’s represented by the same agency as Ten Hag, but he cost €75 million this summer, and he hasn’t scored or assisted a single goal in the Premier League yet.

In transfer-fee terms, United’s investment in Antony and Hojlund has yielded one goal for every €42 million spent. Put another way: that’s the same fee Liverpool paid to acquire Mohamed Salah from Roma in the summer of 2017.

3. The manager, Erik ten Hag: Bad decisions, no style

We tend to overestimate the importance of the manager to team performance simply because it’s easier to blame or praise the guy on the sideline instead of grappling with the fact that soccer is a complex, dynamic, and frequently incomprehensible game. That’s not to say that managers don’t matter at all, or that managers can’t have a large effect on team performance, but rather that we can’t really know what aspects of what we see every weekend deserve to be credited to the manager. A good rule of thumb, in the short term at least, is to fight back against the urge to credit or blame the coach too much for a team’s successes or failures.

From the outside, though, there are two concrete things we can see a manager affecting: who plays and how the team plays. This is where Ten Hag has contributed to United’s struggles.

In his first season at United, Ten Hag made one clear personnel decision: he didn’t want Cristiano Ronaldo. Despite a still-impressive goal tally, massive wages, and towering fame, Ronaldo had been making his teams worse for the past few seasons because of his inability to press or really contribute in build-up play. Ten Hag recognized this, picked a fight with one of the most famous and public-facing athletes on planet earth, dropped him from the team, and almost immediately saw his team rise up the table and finish all the way up in third.

This season, though, Ten Hag’s personnel decisions have been harder to understand.

First, there’s the ongoing feud with Jadon Sancho. He hasn’t lived up to his transfer fee or his elite performance at Borussia Dortmund, but he still should easily be good enough to contribute significant minutes to a team that’s scored fewer goals than it has conceded.

Over the summer, Ten Hag stripped the captaincy from Harry Maguire … and now Maguire is back in the team, seemingly as the club’s first-choice center-back. Meanwhile, he gave the captaincy to Bruno Fernandes — the team’s best player, but also someone with a tendency to lash out at refs, opponents, and teammates whenever the team was struggling.

Acquired from Real Madrid last summer, center-back Raphaël Varane doesn’t play anymore, for no apparent reason other than Ten Hag has decided he doesn’t want the player anymore. Mason Mount was signed for €64.2 million over the summer from Chelsea, and although he’s been struggling with injuries, he, too, had fallen out of the starting lineup when healthy.

Every manager who turns around a big club seems to make at least one big decision to leave out a talented player for the greater good of the team. Last year, Ten Hag did it with Ronaldo, and it was a smash-hit. This season, though, he’s continued to make lots of decisions, and none of them have improved the team, which brings us to the second identifiable aspect of managing from the outside: style.

When Klopp, Guardiola, and even Arteta took over their current clubs, the way their teams played changed almost overnight. This speaks to each coach’s ideas to craft a coherent vision, and then do whatever behind-the-scenes work is needed to get the ideas across to their players and have them execute on it.

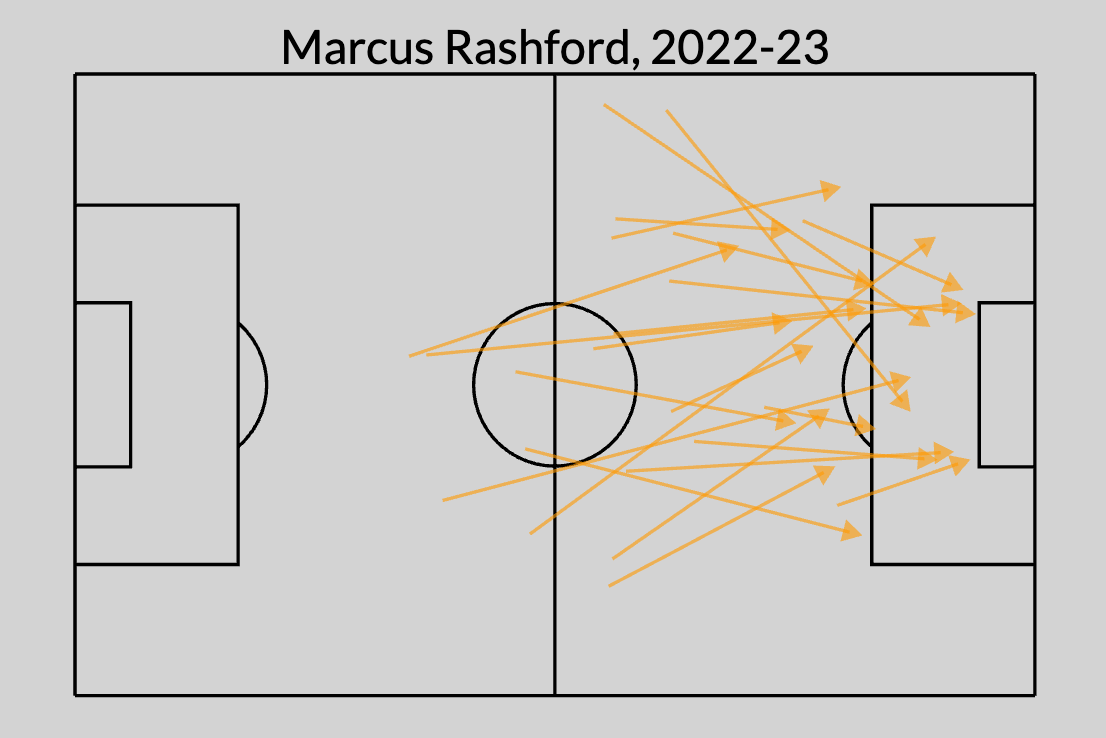

At the beginning of last season, Ten Hag tried to port his preferred approach from Ajax — high-wire build-up play out of the back — over to United, and it was a disaster. To his credit, the team quickly moved away from that approach and gave up trying to control matches. Instead, they focused on finding ways to get Marcus Rashford free and in spce, running in from the left wing, and having their midfielders make runs into the penalty area.

This season, does anyone really know what United are trying to do? They’re sort of trying to control possession and kind of trying to press and occasionally trying to play quickly, but there’s really no cohesion to their approach. Across their last four matches, they’ve conceded more than 20 shots twice and also attempted more than 20 shots twice. The average Premier League match averages 26 shots from both teams combined.

4. Injuries

A simple way for your team to get worse is for your best players to not be available for selection. And that’s been true for four of United’s key pieces from last season. It’s not purely injury driven, but Luke Shaw, Christian Eriksen, Casemiro and Lisandro Martínez have featured in significantly fewer minutes this season than last.

- Shaw: 74.6% last season, down to 35.6% this season

- Eriksen: 59.9%, down to 42.2%

- Casemiro: 62.1% last season, down to 45%

- Martinez: 61.8% last season, down to 26%

Martinez is a big loss, but the decline in playing time from the other three shouldn’t surprise anyone. Casemiro and Eriksen were both 31 at the start of the season, while Shaw has never played more than 2,000 minutes in consecutive Premier League seasons. I don’t think the injuries to these four players come close to explaining United’s year-to-year decline, but even if they did, these are the built-in risks you take by acquiring older players like Eriksen and Casemiro.

When three of your most important players are old and/or injury prone, there needs to be a better backup plan. See numbers 1-3 on this list.

5. A decline in player performance

United have three player types on their roster: 1) 30-plus guys, 2) guys who aren’t good enough, and 3) Marcus Rashford, Bruno Fernandes, Luke Shaw or Lisandro Martinez.

I wouldn’t blame someone like Victor Lindelof or Diogo Dalot or Aaron Wan-Bissaka or even Antony for United’s struggles, because they’re all who they are: mediocre Premier League players. They’re just not good enough for a team with this much money.

And then there’s the 30-plus group, which includes the likes of Casemiro, Eriksen, Maguire and Varane. On the whole, we should expect the four of them to perform at a lower aggregate level than last season because that’s what happens when you’re in your 30s: you get worse, you get injured, or both. Again, I don’t think you can blame a 30-something player for a decline in performance. Time passes — you can’t do anything about it.

So, United really only have four key players who have performed at a consistently high level before and who are still in their 20s. The impact of Shaw and Martinez has diminished from last season because they’ve both been hurt. Neither one has really played enough to pin United’s struggles on their lack of form.

That, then, brings us to Rashford, who’s been dropped for the past few matches, and Bruno, who’s suspended for the Liverpool game.

Rashford’s role in this team is to stretch the defense and create goals. Compared to last season, he’s actually receiving more progressive passes per game and taking more touches in both the attacking third and the penalty area. But he hasn’t been able to get in behind the defense as often. Last season, he received 22 through balls, second in the league behind Manchester City’s Erling Haaland:

This year, we’re almost halfway through the season and he’s received just three through balls. Without as many free runs in behind, his goal-scoring is down significantly — 0.53 non-penalty goals per 90, to 0.08. And while that discrepancy overblown purely by some finishing variance in both directions, his non-penalty xG per 90 has also declined from 0.48 per 90 to 0.32. Rashford isn’t playing as well this season, but he’s also not being helped by the larger dysfunction around him.

Bruno’s attacking output has also declined from last year to this year — 0.68 non-penalty expected goals plus expected assists per 90, down to 0.54 — but the latter number is still right in line with his career average at United of 0.56. He’s also playing more passes into the penalty area than ever before, while taking fewer touches inside the penalty area than ever before.

Taken together, Rashford’s inability to get behind opposing defenses and Bruno’s drift deeper speak to larger structural issues rather than individual struggles. But perhaps there’s a simpler way to look at this.

Last season, Rashford and Bruno had career years, vaulting United up the table. This season, neither player has been as effective. Thanks to injuries elsewhere on the roster, poor management from the coaching staff, even worse recruitment from the front office, and more than a decade of neglect from ownership, there’s still no one else capable of picking up the slack.

Credit: Source link