An ice-cold Garden bow will live forever in Trae Young lore.Is the Hawks’ All-Star hero , a villain or something much more?

Think of the moment. Before Trae Young takes the court in the NBA All-Star Game on Sunday, think of the Trae Young moment we all know: The Atlanta Hawks up 12 in Game 5 in the first round of the Eastern Conference playoffs against the New York Knicks at Madison Square Garden, less than a minute to go in the game. Trae Young dribbling, idling, then hoisting up a step-back 3-pointer from the edge of the Knicks logo, swishing it with 43 seconds to go, then strutting to half court to bow. Think of how many moments are inside that moment, how many moments brought Trae there, how many moments he will yet live in the shadow or light of that one.

YOU CAN TRACE that moment back to Pampa, Texas.

Trae’s great-grandfather Eugene Young moved to that speck of a city as a boy in the late 1950s. Eugene’s obituary says, “He was a sports enthusiast, but basketball was his favorite to watch.” It became a family obsession. Eugene’s son, Rayford Sr., routinely sat his grandson Rayford Young III (Trae) down in front of the TV to watch NBA games. There, in a large den where he’d let Trae dribble a ball around, Rayford Sr. would point out his favorite players to Trae and describe their pet moves. “Basketball was all we talked about, that’s all we did,” Trae’s father, Rayford Jr. (Ray), says.

“We couldn’t come home and tell someone in the family we got outplayed on the basketball court,” Trae’s great-uncle Rodney Young says.

Ray insists his Uncle Rodney, one of eight boys and still living in Pampa, was the best player in the family until Trae. Uncle Rodney says the men in his family dreamed of making it to the NBA: “When my brothers played, other people would say, ‘Well, y’all good enough to be in the pros,’ and stuff like that, and nothing ever worked out. Then Trae comes along.”

He says Trae’s daring and combativeness on the court descends from a line of uncompromising people: “We were raised in West Texas. My grandmother used to say, we hardly cry at funerals.”

Think of the shot and the bow in the Garden as Trae’s inheritance. Think of Uncle Rodney crying in Radio City on draft night in 2018 as Trae walked across the stage. Listen to him when he tells you Ray was one of the first players he remembers shooting a step-back 3, and when he tells you Trae firing that dagger felt “like everything just came full circle.”

THINK OF THAT MOMENT as there he goes again. Remember it as an escalation, how he’d already hit a game-winning floater in Game 1 with 0.9 seconds to play and then shushed the crowd, shouted, “It’s quiet as f— in here”; how he’d been spit on and cursed at by a singing New York crowd: “F— Trae Young.” Remember how defiantly he walked off the MSG floor after a Game 2 loss brandishing his fingers in an inverted peace sign (an “A,” for Atlanta) and yelling defiantly, “I’ll see you in the A.”

Trae Young has been taunting thwarted crowds since he was at Oklahoma’s Norman North High, shutting up the student section of crosstown rival Norman High after dropping 42 points and a game-winning jumper with 1.4 seconds to go. They chanted “overrated.” He took that personally, to crib a phrase. At the end he took a bow. He took two, in fact.

He’s unusual in that he doesn’t tune his surroundings out, instead opening himself up to the push-pull of energy around him, the waves of noise and information hitting his skin.

“My head is spinning,” he says. “You just know everybody is looking at you. As a 19-year-old, 20-year-old, now I’m 23, it’s like every year has been a moment where I know everybody is looking. It’s like you feel the eyes. You just feel when you’re dribbling up and the crowd starts standing up and everybody knows you’re on, and you’re on fire, and the defense knows, your teammates know. And you know.

“The world of people in the arena is watching you with the ball. … You dream of those moments. I think about those moments all the time. And so, whenever they come, I’ve already thought about it. I’ve already envisioned what’s going to happen.”

His parents knew what was coming that night in the Garden. “He just started looking different, I could see it in his eyes,” Ray says. Sometime late in the fourth quarter of Game 5, Trae’s mother, Candice Young, turned to her husband and said, “He’s gonna bow. He’s gonna bow at some point.”

THINK OF THAT MOMENT in the Garden as a “f— you to New York.” “That’s what it was,” Spike Lee says. “You just got to shut up. What can you say? He was killing us.”

Trae’s buddy, the rapper Quavo, still laughs at the memory. “Oh man, the disrespect was crazy,” he says. “He felt like a villain; he felt like it was him against the world.”

Hawks CEO Steve Koonin, who knows a marketing coup when he sees one, calls it genius: “I’ve been around a long time. I’ve never seen anything like that. That was spectacular. And his answer in the press conference, ‘I know what happens in this town at the end of the show, they take a bow,’ was genius. I don’t think there’s another word for it other than genius.”

So think of it as a warning too; Spike does. “Some cats are built for this, and they feed off it,” he says. “So just leave him alone.”

Trae demurs: “I don’t know. I don’t know. I feel like if you got to meet me, you wouldn’t feel like I’m a bad guy or anything like that, or a villain that some like to make me out to be.”

This comes moments after he tells me he had planned the bow in the Garden days before he took the shot.

His high school coach, Bryan Merritt, remembers once stalling the team bus for him after a game. Merritt was used to this by now, Trae’s media requests and autograph sessions, but this was taking longer than usual. He got off the bus and went back into the gym to look for Trae.

“There’s three grown men with basketballs … they’re 40-something, and they’re asking Trae to sign autographs and stuff like that,” Merritt recalls. “It’s 11 o’clock or whatever at night. So I had to basically drag him away and say, ‘Man, y’all catch him when he gets in college or something. He needs to go home.'”

The atmosphere around Trae got so hectic — media and autograph requests, people finding their way into the locker room — that Merritt eventually assigned one of his young assistant coaches, Jake Rudd, to shadow Trae: part confidante, part security, part PR handler. Trae even stopped riding the team bus, driving to games with Rudd and a couple of teammates. A few coaches and players started affectionately calling Rudd “Turtle,” a character from HBO’s “Entourage.”

“I feel like if you got to meet me, you wouldn’t feel like I’m a bad guy or anything like that, or a villain that some like to make me out to be.”

– TRAE YOUNG

Things escalated in college, where Trae spent a few months as a freshman being one of the most talked-about players in the country at any level. He was compared to Steph Curry. LeBron James told him to leave for the NBA. Dick Vitale tweeted he was the best college guard since Isiah Thomas in 1981. ESPN started showing a chyron of Trae’s stats even in broadcasts where other teams were playing. Trae became, and remains, the only Division I player to lead the nation in points and assists per game.

“It happened overnight,” Ray says. “From no phone calls or maybe a handful, to now you have every financial adviser that you can think of or every big financial institution calling you, wanting to work with you. Every sports agent wanting to work with you, every marketing corporation wanting to work with you.”

“You remember how everyone loved Zion when he was at Duke?” he asks. “Trae was Zion before Zion.”

CONSIDER THE MOMENT the result of a long memory.

Almost exactly three years before the bow in MSG, Trae’s first two NBA summer league 3-point attempts were air balls. It’s hard to remember that now, which is worth remembering. His father, Ray, remembers it clearly, he remembers the sports shows talking about it, which is also worth remembering.

In the second half of Trae’s freshman year at Oklahoma, the losses piled up (Oklahoma went 2-9 after January) and the hyper-attention soured. Journalists started writing headlines like, “The Trae Young Experience has become too much for some to take.” In a game against Texas Tech in Lubbock — the city where he was born, against the school where his father had scored more than 1,500 points — Trae went 0-for-9 on 3-point attempts, the only game that season where he didn’t make a 3. Fans in the packed arena called him outside his name. Ray says it’s the first time he ever heard a crowd chant, in unison, ‘F— Trae Young.'”

Trae began saving screenshots of negative headlines and comments online and reading them to himself before games.

“I was going through a little phase,” he says. “I always wanted to remember their names. I always wanted to remember the people who said what they had to say.”

Minutes before it happened, Ray and Candice Young sensed their son’s plan for a Garden goodbye. “He’s gonna bow,” Candice told Ray. “He’s gonna bow at some point.” DIWANG VALDEZ FOR ESPN

THINK OF IT as necessity, the way Trae Young had to be.

At just over 6 feet tall and 164 pounds, Trae isn’t an imposing figure on a basketball court. His presence invites challenge. “He just looks like a regular dude out there,” Merritt says. “So maybe people think they can get under his skin or whatever, bother him, and that’s why people get after him so much.”

Even after he has put up 40, people watch him and can’t quite believe what they see.

He has to nutmeg you with a dribble, embarrass you, hit the game winner in your face and laugh about it, knock you out of the playoffs and take a bow about it — until you learn.

“I know it’s going to continue to happen, till I’m probably done playing. It’s something that’s happened my whole career. I’ve had to defend myself in a lot of cases, but I’m always up for the challenge,” Trae says.

“These other dudes that he’s killing, they got a lot more in terms of God’s gifts than Trae does,” Merritt says. “So, if he doesn’t go out there and have that chip, he wouldn’t be half the player he is.”

His grandmother Shirley saw that chip on his shoulder long before Merritt did. When Trae was in elementary school, he used to race his grandmother on bikes all the time. One time he fell. “I thought he hurt himself and I cried for him,” she says. “He wouldn’t cry. And he said, ‘Grand mom, don’t cry. I’m OK, I’m OK, I’m OK.’ And we got up and he wanted to race again.”

Think of the decision Trae didn’t make.

Early in Trae’s senior high school season, Kentucky basketball coach John Calipari flew to Oklahoma hoping to get a commitment from the five-star recruit.

Coach Cal sat in the Young family’s living room. The house smelled like Pine-Sol — Trae’s mother had been cleaning in preparation. Calipari made small talk with Timothy, Trae’s little brother, and then pulled out a notebook and started his pitch. He read off names like Anthony Davis, Karl-Anthony Towns, Devin Booker. … And draft rounds: first, first, first. … And the NBA contract figures of his former players, totaling in the billions of dollars.

Come to Kentucky, Calipari said. I’ll make you a first-round pick. I’ll make you millions of dollars.

Trae listened to this calmly, politely. He asked questions about Kentucky’s style of play but mostly gave nothing away, as his parents had taught him. Interested, not needy. A couple of weeks before Calipari it was Duke’s Coach K, a couple of weeks before that it was Kansas’ Bill Self.

Trae listened and said, No thank you. It would be Oklahoma, a few minutes down the road.

“Nobody has more confidence in me than myself, because I knew the work that I put in at 6:30 in the morning when everybody was asleep,” Trae says. “It was an honor to hear Coach Calipari say that stuff about me, but I knew I could do it anywhere.”

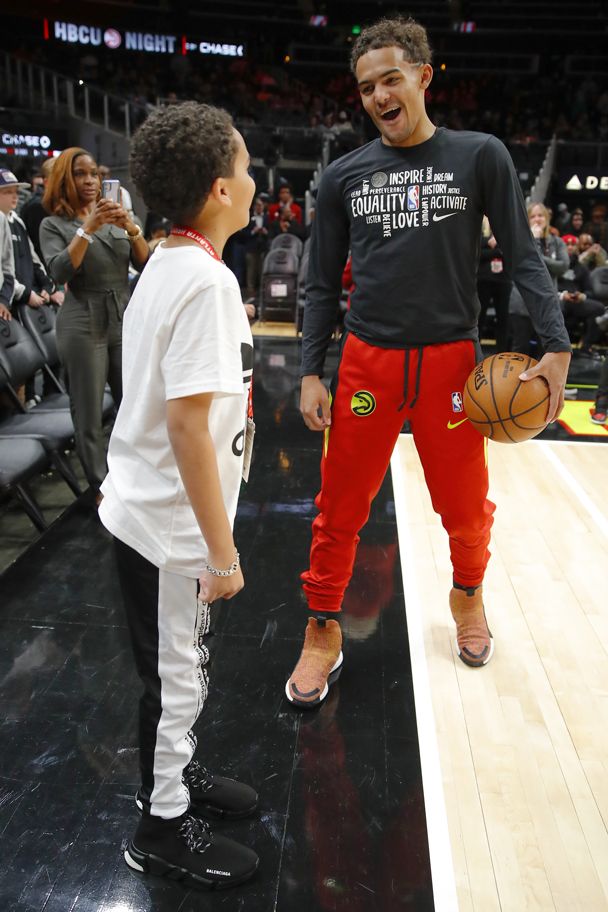

Believe it or not, life as 11-year-old Timothy Young doesn’t look half-bad to Trae Young. TODD KIRKLAND/GETTY IMAGES

NOW THINK OF the contradictions in the moment — the gaudy star-making turn of a soft-spoken, private young man. A player who shoots from logos, nutmegs defenders, jaws with fans, who has a signature Adidas shoe, a top-10 selling jersey and one of the most marketable profiles in the league but who will nevertheless tell you the person he’d most like to be besides himself is his 11-year-old little brother, and the place in the world he’d most like to live besides Atlanta is where he grew up, in Norman, Oklahoma.

Rudd, who is still in touch with Trae, describes him “as a very boring person. He’s about basketball and getting better. That’s who Trae is.” Quavo calls him a “homebody.” After games, Trae goes home and re-watches his games. On his off-days, he does recovery work or mostly watches movies at home. The new “Venom” and Kevin Hart’s “True Story” are a couple of his favorite movies and shows right now; Lee’s “He Got Game” might be his favorite movie of all time. He loves the “Superman” films, the Christopher Reeve ones. “The new one, where he be getting beat up by Batman? That’s another story. I can’t stand that,” he says.

So Trae takes the bow, that preplanned bit of showmanship, and longs for quiet pleasures — the baby brother “able to go to NBA basketball games and be a kid.”

And Trae takes the Garden by storm, but knows what a stage is and what it’s not: “I like Oklahoma,” he says. “I like the privacy it brings, and people don’t like it, but if you’ve been there, you know everywhere. It’s really a nice place to live.”

THINK OF THE QUESTIONS that hang over him and his moment. Questions about how to be.

When I tell his father that Trae said if he could be anyone but himself he’d be his little brother, Ray reflects on their relationship.

“He made that comment because he knows I don’t push Timothy as hard as I pushed him,” he says.

“And I know sometimes Trae and I, we would butt heads and we would argue and he wouldn’t agree with a lot of stuff that I wanted him to do because maybe he felt that I was living my life through him. And he doesn’t see that with Timothy and I in our relationship.”

Candice interjects, “I think what Rayford said, a lot of that is true, but I also think that Trae likes Timothy’s swag.”

Young has always been his team’s best player, and now he understands he also needs to be a leader. “Trae blends in in a locker room,” Hawks guard Lou Williams says. SCOTT CUNNINGHAM/GETTY IMAGES

THINK THAT THE MOMENT isn’t enough. That if Trae Young doesn’t make us basically forget about that step-back in the Garden, if he doesn’t create bigger, more consequential moments, he would have failed his own promise.

Trae is 23 years old, recently engaged, and in his fourth season in the NBA and heading to his second All-Star Game this weekend. Last season, he led the Hawks on a thrilling playoff run during which they throttled the Knicks and ended Philadelphia’s ballyhooed Process™ before succumbing to the eventual champion Milwaukee Bucks in the Eastern Conference finals. This season, Trae is fifth in points per game (27.8) and tied for third in assists (9.3), the only player in the league to be top five in both categories. He is a virtuoso of the ball screen, effortlessly manipulating its variations. Despite his size, he can at times seem unguardable.

Trae was shut out of last year’s All-Star Game, held in Atlanta. Ray insists that Trae isn’t going into this year’s All-Star Game with an agenda. “He’s past the point of wanting to prove people wrong,” Ray says. “It’s more about going out there and making his close family members proud and proving the fans who voted for him, proving them right.”

But Trae was left so disappointed with his omission last season that he couldn’t stand to be in Atlanta the weekend of the game, decamping to Florida for a few days. Ray told Trae to think about how it was in high school, how it had always been on the court for him. “If there’s gonna be a question, you’re never gonna get the benefit of the doubt,” Ray said. “So you have to leave it where there’s no doubt.”

His scoring was down from the season before, but the Hawks were winning more, and playing better basketball, Trae thought. The next few months would prove him right. By March 7, the day of the All-Star Game, the Hawks were two games into an eight-game winning streak that would see them finish on a 27-11 run under interim head coach Nate McMillan, who had replaced Lloyd Pierce in the middle of the season. They took that momentum all the way to the Eastern Conference finals.

The Hawks this season hover under .500, clinging to the last play-in position and struggling to cohere in the face of injuries and illness that have troubled the consistency of their lineup and rotation. Their offense remains elite, bolstered by Young’s exceptional productivity and increased efficiency. He has scored 40 or more five times this season, tied for fourth most in the NBA. And ranks second in assist percentage. But if they want to win titles, he’s going to need to do more.

“He knows for his team to win he’s got to be a leader and put up stats and help make all his teammates better,” Ray says.

SO, FINALLY, CONSIDER the possible futures Trae Young’s moment suggests.

Trae is very much a developing player, with a team that’s growing up with him. McMillan, keen to emphasize all the ways in which Trae is learning and growing, won’t even talk about what kind of leader Trae is. He considers the answer TBD. “You can’t force people to be leaders,” McMillan says. “I don’t think you can force that on a guy. I think he has to develop that and that’s something that he’s working on. Again, the expectations change, it changed from last year to this year. We’ll see what that becomes, but I think it’s too early in his career to say what that is.”

This is no secret; Trae’s teammates will tell you. “Trae blends in in a locker room,” says veteran Hawks guard and three-time Sixth Man of the Year Lou Williams. “I think he’s still trying to find his way, as far as being a leader. … He has tremendous respect for the older guys. … He just shows a lot of respect, he don’t really demand much. He don’t really ask for much. He kind of follows our lead. And so, in his maturation, that’ll be his next step is to kind of command that respect from guys and run a locker room how he likes it to run. Because that’ll translate out on the floor.”

Trae’s high school and college coaches say, at those levels, his on-court brilliance preempted the skill of leading a locker room with his voice, of managing personalities. Trae himself will tell you it’s an area of growth.

“Being that younger kid playing with older guys, I was never the loudest in the room,” Trae says. “I was always just the good player, and everybody would just follow my lead. But now as I’m getting older, a point guard in the league has got to be able to be vocal.”

“You ever see ‘Drumline’?” McMillan asks.

“OK, you remember when the director said: We’re going to mix a little old school with the new? And they went and put out a performance that won them the BET classic. That’s pretty much what I want from Trae, that’s the things that we talk about, but I don’t want, we’re not going to take your game, I don’t want to take your game away from you. He goes, and he pushes, and he attacks, but sometimes you got to put a little old school in there and you got to slow up … so mix a little old school in there with your new school.”

Then McMillan turns to one of his favorite metaphors.

“At that point guard position, you could be a cloud or you could be sunshine. And sunshine is a player that your teammates, they just light up when they play with you, because they know that it’s going to be fun,” McMillan says.

Think of Trae Young’s moment as light, then — and the Garden a dichroic crystal. Think of the moment as a property of light — its ability to be dispersed into its component colors.

“Steve Nash was sunshine, Magic Johnson’s sunshine and Steph Curry is sunshine,” McMillan continues.

Trae Young is …?

“I think he has a special talent that we haven’t really seen at that position, his ability to score, as well as facilitate,” McMillan says. “I think he can be sunshine.”

Credit: Source link