If you want to feel good about Arsenal, here’s how to do it.

You look at the table, and you see the team in fifth place, one point out of fourth. Given that they’ve finished eighth in manager Mikel Arteta’s first two seasons at the club, that’s progress! Well, until your eyes continue to scan to the right and you see that they’ve actually been outscored by three goals over the course of 14 matches. Given that only one team has finished in the top four with a negative goal differential since the turn of the century, that’s not progress.

But that second point ignores just how Arsenal got their goal differential.

Three of the five best teams in the world right now are in the Premier League. Chelsea, Liverpool and Manchester City are like if there was a third team in LaLiga just as good as Real Madrid and Barcelona in the mid-to-early 2010s. Manchester City has a plus-21 goal differential, Chelsea a plus-27 and Liverpool a plus-31. Figuratively, they’re in their own league; no one else in England even has a goal differential in double digits. In all six matches against the Big Three this year, everyone else is going to be a massive underdog. Maybe you luck into a win or grind out a draw here or there, but the expectation ahead of each match is zero points.

Sure, Arsenal have been systematically obliterated by Chelsea, Liverpool and City to varying degrees — zero goals scored and 11 conceded — but what if that’s actually a feature and not a bug of Arteta’s tactics?

Along with Manchester City, per Stats Perform, the Gunners are joint-lowest in pass velocity — the number of passes per seconds of possession — with Manchester City. A slow and deliberate midfielder himself, Arteta has seemingly crafted a team in his own image. It’s been a disaster against the best teams; you beat them by countering quickly into space. But given that Arsenal have more money and (theoretically) more talent than most of the other teams in the league, dominating the ball and methodically working it into scoring positions works against everyone else.

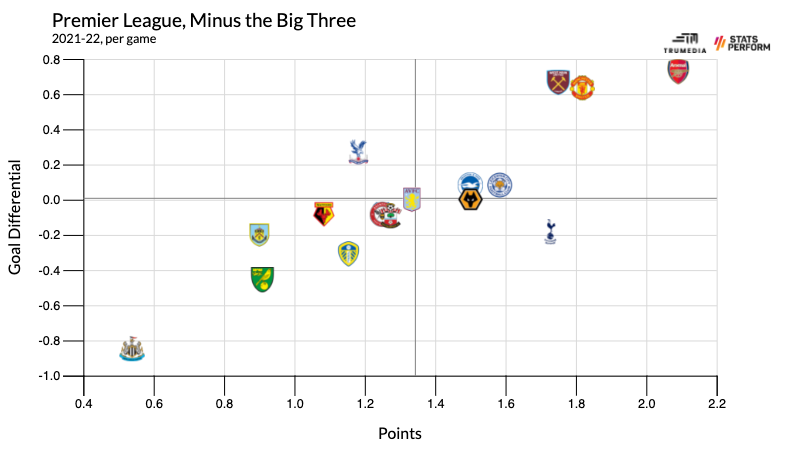

If you remove Liverpool, Chelsea and City from the table, Arsenal are in first place, even after Thursday’s loss to Manchester United. They’ve not only taken the most points per game from the matches against what we’ll call the “Little 17,” but they also have the best goal differential. Sure, you’d rather not get embarrassed every time you match up against one of the big dogs, but you play 32 games against everyone else, and those matches will ultimately decide whether or not you finish in the top four. Finish top four, and you get more money, and you can buy better players, and you can stop falling apart every time you play the Big Three.

If you remove Liverpool, Chelsea and City from the table, Arsenal are in first place, even after Thursday’s loss to Manchester United. They’ve not only taken the most points per game from the matches against what we’ll call the “Little 17,” but they also have the best goal differential. Sure, you’d rather not get embarrassed every time you match up against one of the big dogs, but you play 32 games against everyone else, and those matches will ultimately decide whether or not you finish in the top four. Finish top four, and you get more money, and you can buy better players, and you can stop falling apart every time you play the Big Three.

It’s a nice story. There’s just one problem: It’s probably not true.

One of the most volatile teams of the modern era

If you’ve heard of “expected goals,” Michael Caley is one of the main reasons why. Back in 2013, he created his own xG model at the Tottenham Hotspur fan-blog, Cartilage Free Captain. He made the methodology public and worked through the problems out in the open. Before xG made it to ESPN broadcasts and Match of The Day on the BBC, Caley was pumping out xG totals from his Twitter account.

After helping popularize the sport’s most fundamental advanced stat and then taking a break from blogging for a couple years, Caley realized there was still plenty of work to be done.

“Generally, I think there is kind of a ‘missing middle’ in analytics, where lots of relatively standard sports analytics questions didn’t get answered sufficiently in the public domain because the take-up of analytics has been so quick compared to many sports,” he said. “Bloggers had less time in the wilderness before they could get jobs at clubs, and a lot of work never got done, at least in public.”

The strangeness of Arsenal’s season inspired him to start his search for the middle.

As part of an offering for paid subscribers to his podcast, The Double Pivot, Caley analyzed 1,294 individual team seasons across the past decade in Europe’s Big Five Leagues for a study titled, “Expected Goals, Predictiveness, and Variance.” Basically, he wanted to know whether there have been teams like Arsenal in the past and whether removing outlier results, like Arsenal’s blowout defeats against the Premier League’s Big Three, created a clearer picture of how a team was likely to perform in the future. He looked at every team’s first 12 matches, and then compared them to their performance over the rest of the season.

So just how weird have Arsenal been this season? “Arsenal are very weird,” he said.

Among all the teams in Caley’s database, Arsenal’s match-to-match performance (as measured by xG created minus xG conceded) had the sixth-highest standard deviation. In other words, through the first 12 matches of the season, Arsenal have been one of the most volatile teams of the modern era. Following Mikel Arteta’s team has been like staring at a seismograph in the middle of a massive earthquake, except earthquakes only tend to last for about 30 seconds.

“On the specific issue of teams that ‘play well against bad teams, get annihilated by good teams,’ these are really really hard to find,” Caley said. “There is no correlation between having a high standard deviation early in the season, and having a high standard deviation through the rest of the season. Teams like Arsenal tend to have much more normal results as the season goes along.”

There have been a couple of teams like Arsenal in the past. In the 2011-12 season, Tottenham lost both of their first two games, against the two Manchester clubs that would end up even on points atop the table come season’s end, by a combined 8-1 scoreline. However, they finished the year in fourth place and played much closer matches against United and City in the reverse fixtures.

In 2014-15, Sevilla got smoked by Barcelona and Atletico Madrid early in the season, but drew both of them the second time around, finished fifth and won the Europa League. And in 2017-18, Liverpool lost early-season games to Manchester City and Tottenham by a combined 9-1 scoreline before ending City’s unbeaten season in January, drawing Tottenham, finishing fourth and reaching the Champions League final.

“All of these teams were, in the aggregate, better than Arsenal, and they tended to play roughly to their aggregate level of performance over the rest of the season, not consolidating all their bad games in a few blowout losses to bad teams,” Caley said. “Generally, there is just very little evidence that teams have a persistent quality of beating the bad teams and being beaten by the good ones. Some of this is surely that good and bad performances are distributed somewhat randomly, players are people and people are weird, stuff happens. But I have a hypothesis that beyond the normal levels of randomness, this is not because such a characteristic is impossible, but because it should be fixable.

“If you are good enough to beat up bad teams, you should have enough quality not to get rocked by good teams. There should be tactical and personnel adjustments available, and you’re able to make use of them. Jurgen Klopp very much did in 17-18. He tightened up Liverpool’s possession play and defensive pressing, scaling back the forward press as time went on. And if you don’t adjust, often you get fired and replaced by someone who will. I guess it’s possible Arteta won’t adjust and won’t get fired and won’t see just regression to the mean, but it would be very unusual.”

Expect their season to get worse, not better

While it’s unlikely that Arsenal continue with their current profile, Caley found that throwing away the outliers made projections of future performance worse. “You get better results statistically if you keep all of a team’s results and aggregate them when estimating team quality,” he said.

Like a lot of great analytical work, Caley’s eventually provides us with an obvious conclusion: Of course a team is going to artificially look a lot better if you ignore all of their worst games.

As of Dec. 3, Arsenal’s aggregates are as follows: tied for 10th in goal difference (minus-3) and 14th in xG differential (minus-4.09), per Stats Perform. According to FBref’s Statsbomb data, Arsenal do have the youngest team in the league, when weighted by playing time: 24.8, a full year below Southampton‘s youngest squad.

Among the 11 players to play at least 50% of the available minutes in the Premier League this season, only Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang (32) and Thomas Partey (28) are older than 24. Most of the key players this season are still years away from their primes, and there’s a chance that the likes of Ben White, Bukayo Saka and Emile Smith-Rowe all take leaps at the same time, which would cause an exponential improvement to the quality of Arsenal’s performances. But it won’t happen until some time in the distant future.

As for the best predictor of the rest of this season — what’s already happened this season — it doesn’t look as rosy as what the table might suggest.

“I did find some suggestive evidence that teams which suffered several blowout losses often played a little better than their aggregate,” Caley said. “But the sample is small. It’s only clear when you drill down to about 50 teams. And even if you remove Arsenal’s best and worst performances, their xG differential in the remaining matches is still below average. So even if you do remove the blowouts, what you’re left with is not a very good team.”

Credit: Source link